Terrible Twos: Young Tyrannosaurs Were Careful Predators

Adult tyrannosaurs such as Tyrannosaurus rex may have wielded the strength and size to kill large prey, but it turns out youngsters may had to have been more careful predators, using quickness and agility rather than raw power, scientists find.

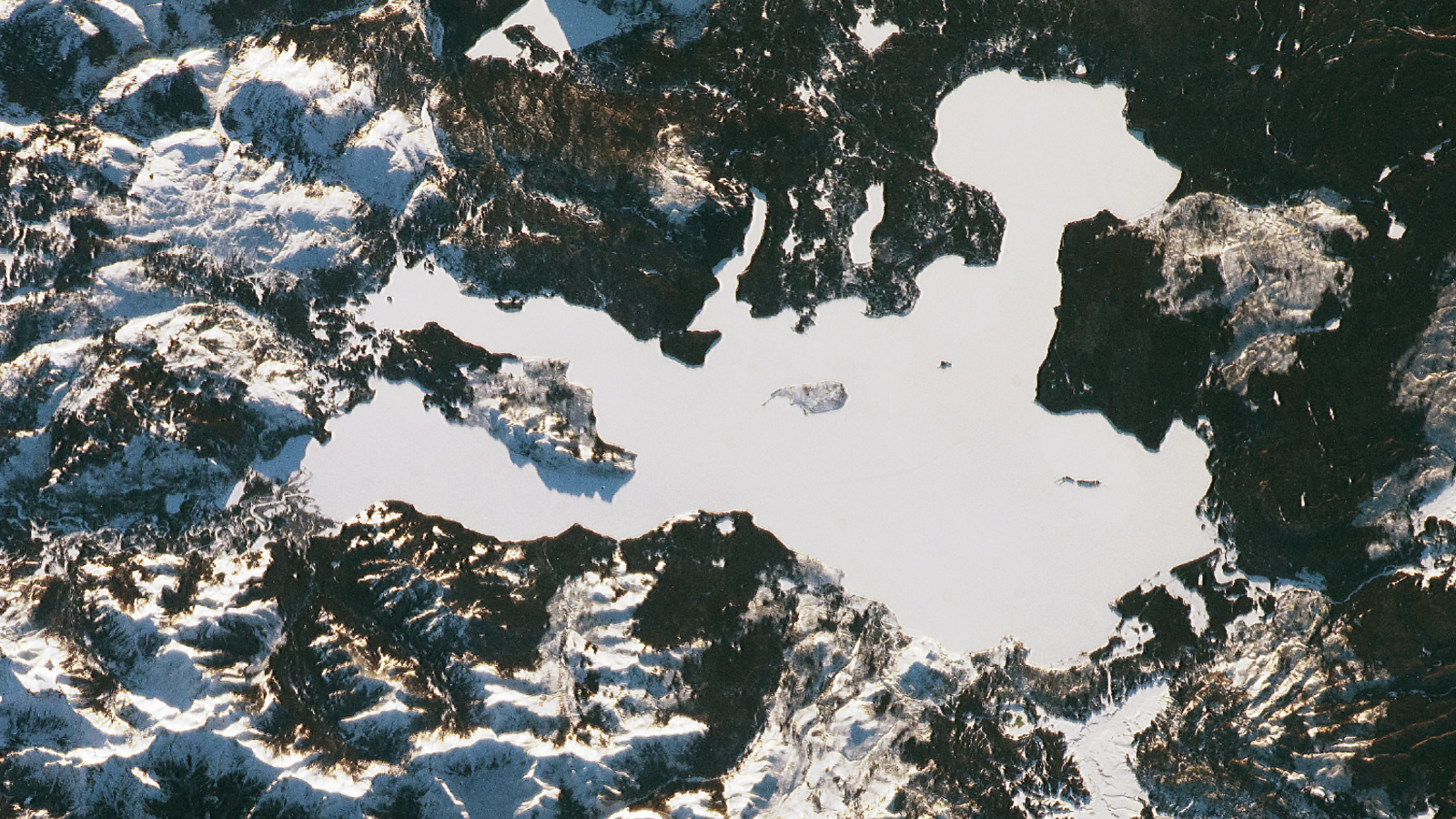

An international team of scientists investigated the youngest and most complete known skull of any species of tyrannosaur, a 70-million-year-old fossil unearthed five years ago in the Gobi Desert in Mongolia. The skull was found as part of a nearly complete skeleton, missing only the neck and two-thirds of the tail, which belonged to a Tarbosaurus, a fearsome predator roughly as large as its closest known relative, T. rex. [The World's Deadliest Animals]

"We knew that adult Tarbosaurus were a lot like T. rex," said researcher Takanobu Tsuihiji at the National Museum of Nature and Science in Tokyo.

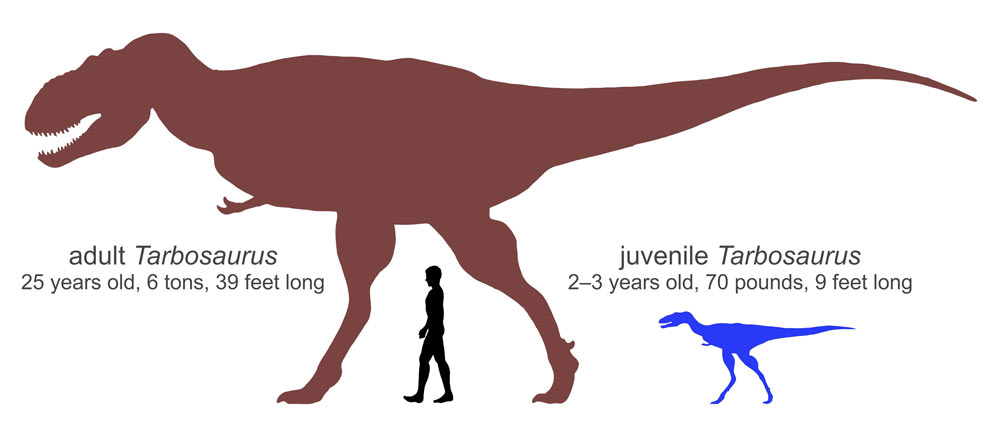

Based on careful analysis of the microstructure of the leg bones, researcher Andrew Lee at Midwestern University estimated this predator was only 2 to 3 years old when it died. It was about 9 feet (2.7 meters) in total length, about 3 feet (1 m) high at the hip and weighed about 70 pounds (32 kilograms). In comparison, an adult Tarbosaurus was 35 to 40 feet (10 to 12 m) long, 15 feet (4.5 m) high, weighed about 6 tons and probably had a life expectancy of about 25 years.

This young dinosaur might have been only 2 or 3 years old, but it was nothing like a human toddler, said researcher Lawrence Witmer, an anatomist and paleontologist at Ohio University. "It does give new meaning to the phrase 'terrible twos.'"

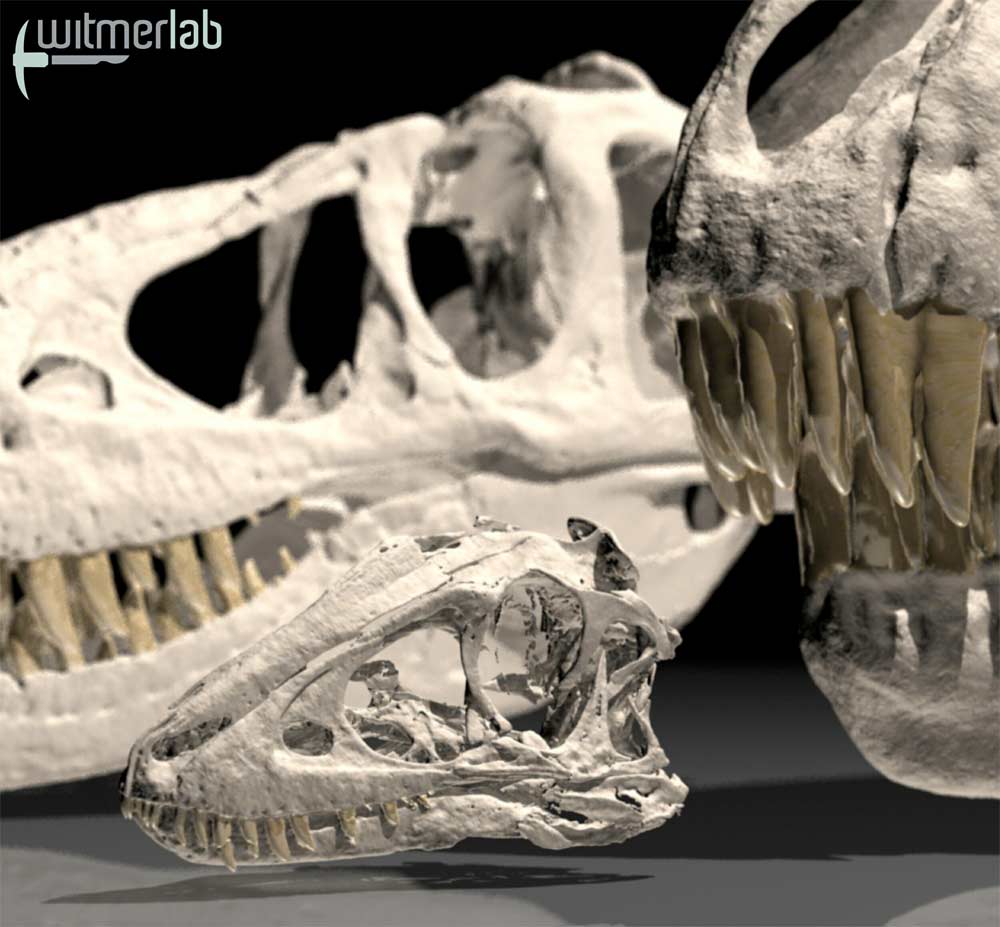

CAT scans of the immature 11.4-inch (29-centimeter) skull revealed that it was far more delicate than an adult's, incapable of handling the kinds of twisting and stress that the reinforced skull of a grown-up Tarbosaurus could.

"Adults show features throughout the skull associated with a powerful bite -- large muscle attachments, bony buttresses, specialized teeth," Tsuihiji explained. In comparison, "the juvenile is so young that it doesn't really have any of these features yet, and so it must have been feeding quite differently."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

This suggests "the younger animals would have taken smaller prey that they could subdue without risking damage to their skulls, whereas the older animals and adults had progressively stronger skulls that would have allowed taking larger, more dangerous prey," Tsuihiji explained.

"This spectacular specimen provides us with a really clear window into how these dinosaurs changed over the course of their lives," Witmer told LiveScience.

The floodplains in which this creature lived offered plenty of options for meals.

"Tarbosaurus is found in the same rocks as giant herbivorous dinosaurs like the long-necked sauropod Opisthocoelicaudia and the duckbill hadrosaur Saurolophus," said researcher Mahito Watabe of the Hayashibara Museum of Natural Sciences in Okayama, who led the expedition that uncovered the new skull. "But the young juvenile Tarbosaurus would have hunted smaller prey, perhaps something like the bony-headed dinosaur Prenocephale."

This range of feeding strategies could have been one of the secrets of success for tyrannosaurs, strengthening their role as the dominant predators of their environments. "The different age groups weren't competing with each other for food, because their diets shifted as they grew," Witmer said.

Witmer and his colleagues next hope to deduce what the brain of this young Tarbosaurus was like based on its skull, "which can shed light on its changing brain structure and maybe even its sensory capabilities as these tyrannosaurs grew," he said.

The scientists detailed their findings May 9 in the Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology.

Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.