Could a High-Fat, Low-Carb Diet Replace Dialysis?

A type of low-carb, high-fat diet that's typically used to manage seizures for children with epilepsy could reverse kidney disease in Type 1 and Type 2 diabetics, a new animal study suggests.

If successful in humans, the so-called ketogenic diet could have the potential to replace dialysis, which is a procedure that artificially filters blood in place of a damaged or failed kidney, said study researcher Charles Mobbs, professor of neuroscience and geriatrics and palliative care medicine at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York City.

"I speculate that this may be useful to completely cure diabetic kidney failure, and I hope that it's possible," Mobbs told MyHealthNewsDaily. "If it's possible, we can potentially not require dialysis. That's a big deal."

However, a lot more research in mice is needed before any studies can be done in humans, Mobbs said, let alone determine if the diet can reverse advanced kidney disease in humans, he said.

"That's the first thing we want to establish in mice: Can we truly reset the clock? Can we completely correct the [kidney] impairments?" Mobbs said.

Other experts say the finding is promising for Type 1 and Type 2 diabetics with earlier-stage kidney disease, but more research must be done to provide evidence that the diet can make an impact on end-stage kidney disease, or kidney failure.

Type 1 diabetes is a chronic disease that occurs when the pancreas cannot produce enough insulin (needed to move blood sugar into cells for energy) to control blood sugar levels, according to the National Institutes of Health. Type 2 diabetes occurs when the body becomes resistant to insulin, leading to high blood sugar levels. Overweight and obesity, a sedentary lifestyle and poor diet are risk factors for Type 2 diabetes, according to the NIH.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study was published today (April 20) in the journal PLoS ONE.

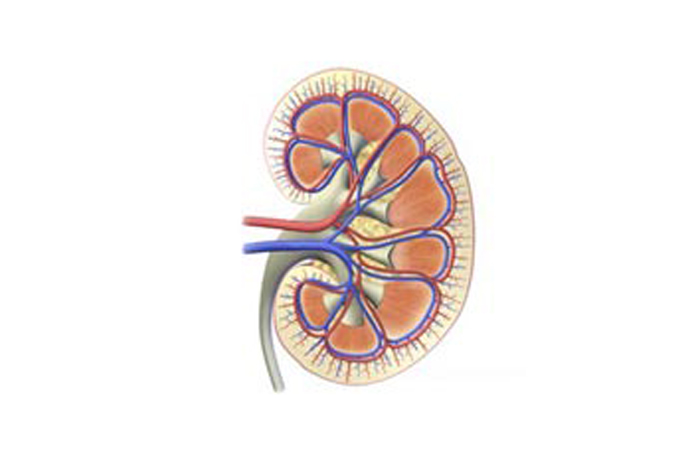

Reversing kidney disease

Mobbs and his colleagues induced kidney disease in mice that were genetically engineered to have Type 1 or Type 2 diabetes. They measured proteins in the mice's urine until levels were 10 times higher than normal, which is a telltale sign of kidney disease.

Then, half the mice were put on a ketogenic diet (87 percent of calories from fat, with a moderate amount of calories from protein and few calories from carbohydrates), and the other half were put on a standard high-carbohydrate diet, according to the study.

After eight weeks, researchers found that kidney disease was reversed, and damage to the organ had been repaired, in the mice that were on the ketogenic diet, the study said, though there was less damage repair in the mice with Type 2 diabetes than the mice with Type 1 diabetes.

Researchers also found that expression of genes that indicate kidney failure were turned off in the mice fed the ketogenic diet, according to the study.

When a person consumes a ketogenic diet, blood levels of ketones are elevated (a state called ketosis). The body's cells are able to get energy from ketones, which are molecules that are produced when fat levels in the blood are high and blood glucose levels are low, Mobbs said. Essentially the body burns fat rather than carbs (called glucose metabolism) for fuel.

"The key to the whole study is that ketones block glucose metabolism," Mobbs said. "Pretty much everybody agrees that diabetic complications are caused by too much glucose metabolism in the cell, so it was kind of an obvious hypothesis that if you can increase ketones long enough, that that would block glucose metabolism and allow the cells to recover from their damage."

However, this is simply a hypothesis — more research is needed to determine the exact mechanism by which ketones work to reverse kidney damage in mice, he said.

"There are a lot of things we don't know yet about how [the ketones are] working," Mobbs said.

It's also possible that the diet works by promoting stem cells to replace damaged cells in the kidneys, he said.

If the findings can be replicated in humans, Mobbs said the diet shouldn't be consumed for long periods of time. Rather, one month of the diet could be sufficient in reversing the kidney damage, he said.

Implications of the findings

Past research has shown that a low-protein diet has a small effect in slowing kidney-function decline in humans. However, that study, published in 1994 in the New England Journal of Medicine, didn't show that a low-protein diet made a difference in people with advanced kidney disease.

However, what may make this ketogenic diet work better than a purely low-protein diet is the fact that the diet induces ketosis (high ketone levels in the blood), said Dr. Leslie Spry, spokesman for the National Kidney Foundation and volunteer professor at the University of Nebraska Medical Center, who was not involved with the study.

"The new part of this would be the ability to achieve and maintain ketosis in an individual with caloric restriction," Spry told MyHealthNewsDaily.

However, Spry said he would be surprised if the diet worked in someone with advanced diabetic kidney disease, because of the great amount of damage to the kidneys that is associated with that stage of disease.

"I would very much doubt that late kidney disease would be reversible, and I would be dubious about that," Spry said. Therefore, researchers must be able to prove that ketosis can actually reverse the effects of kidney disease in humans before the diet can be considered a replacement for dialysis, he said.

Pass it on: Though more research is needed before it can be proven in humans, a ketogenic diet reverses kidney disease in mice with Type 1 and 2 diabetes.

Follow MyHealthNewsDaily staff writer Amanda Chan on Twitter @AmandaLChan.

This story was provided by MyHealthNewsDaily, a sister site to LiveScience.