Gulf's Mysterious Black Corals Are 2,000 Years Old

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

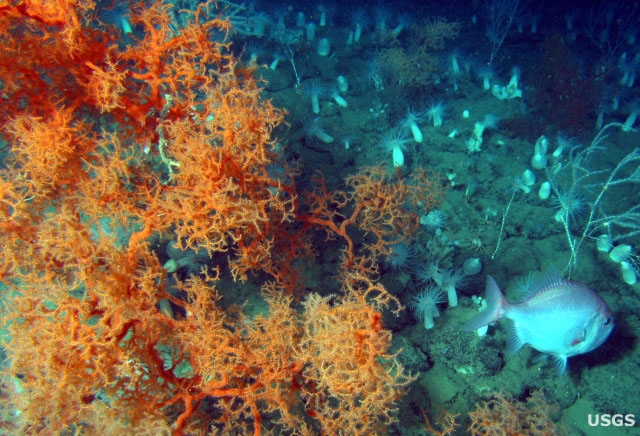

For the first time, scientists have been able to validate the age of the mysterious deep sea black corals found in the Gulf of Mexico. A new study puts them at a venerable 2,000 years old.

Knowing the age of the corals should allow scientists to chart changes in the Gulf's waters through the years.

"The fact that the animals live continuously for thousands of years amazes me," said study team member Nancy Prouty of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

Many of these 2,000-year-old creatures are only a few feet tall. These slow-growing, long-living animals thrive in very deep waters — around 1,000 feet (300 meters) and deeper — yet they are sensitive to what is happening on the surface as well as on the seafloor because they are feeding on organic matter that rapidly sinks to the ocean bottom, Prouty said.

"Deep-sea black corals are a perfect example of ecosystems linked between the surface and the deep ocean. They can potentially record this link in their skeleton for hundreds to thousands of years," Prouty said in a statement.

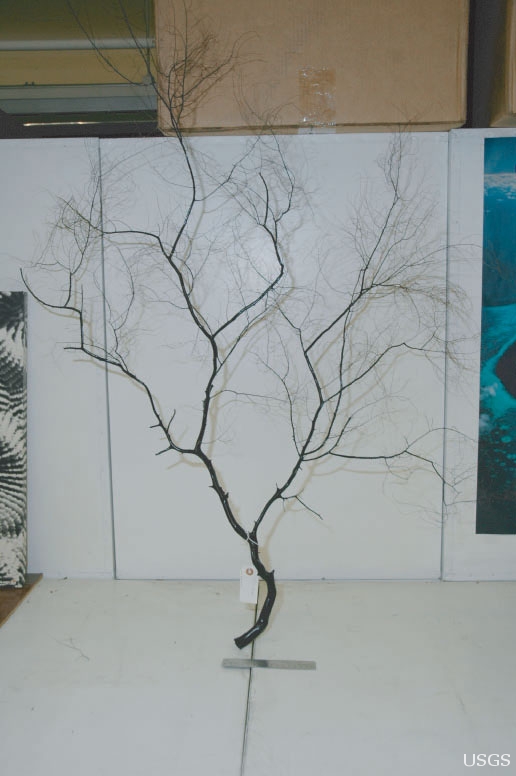

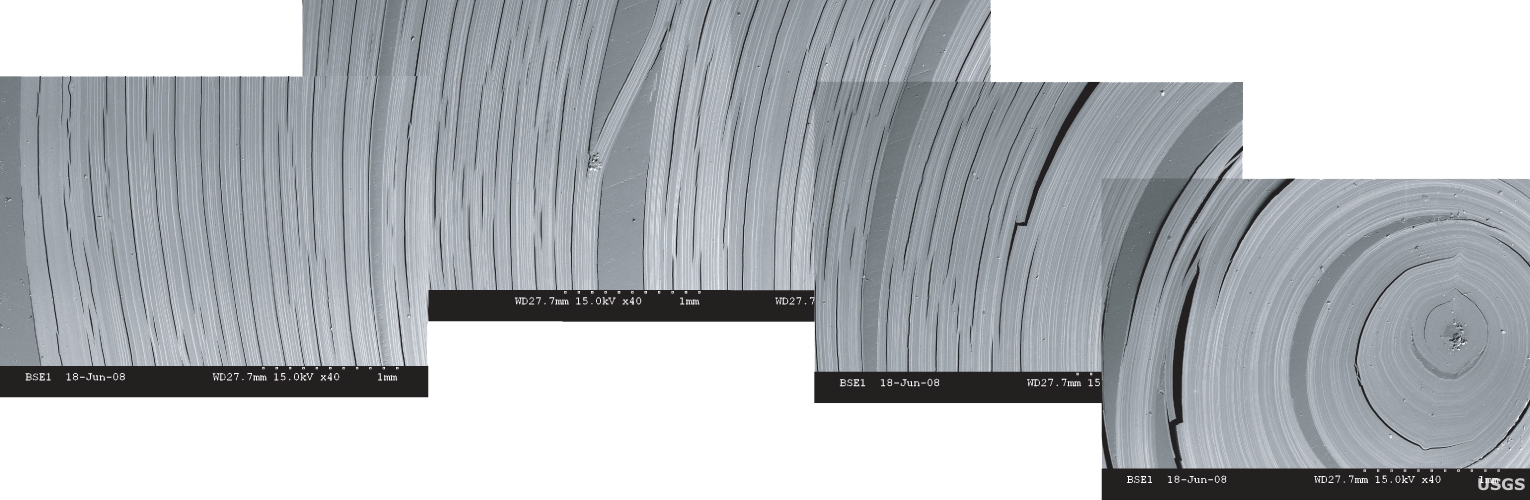

Black corals grow in tree- or bushlike forms, secreting skeletons continuously over hundreds to thousands of years. Viewed in a horizontal cross section, black coral's growth bands resemble tree rings. Human fingernails grow about 1.4 inches (36 millimeters) per year, or more than 2,000 times faster than black coral.

Scientists scoop up these skeletons, date them and use them as yardsticks to measure how the environment has changed, decade by decade, over the last thousand years. These skeletons are like snapshots of the concentrations of carbon in surface waters and the atmosphere from years past.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

USGS scientists and their colleagues, for example, are using these skeletons to measure how the nutrient supply in surface waters has changed, which in turn may reflect the amount of runoff from nearby land surfaces.

The study is detailed in the Feb. 10 online edition of the journal Marine Ecology Progress Series.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus