Horsewhipping Study Whips Up Controversy

People have been whipping racehorses since time immemorial, but until now there has been little research into whether it actually goads them into running faster. Well, it doesn't, according to the authors of a new study, who also suggest the practice is unethical.

"It's the first study to confirm that whipping does not increase the chances of the horse finishing first, second or third," said Paul McGreevy, a veterinary ethologist at the University of Sydney who is a co-author of the new paper. "Ninety-eight percent of the horses were whipped in this study without, on the whole, influencing race outcome."

The study, which has stirred some debate in Australia, was funded by RSPCA Australia, an animal welfare group thatopposes the use of whips in horse racing. One U.S. jockey advocacy group has questioned whether the source of the funding biased the results. Another horse expert says the study was not set up to determine the effect of whips.

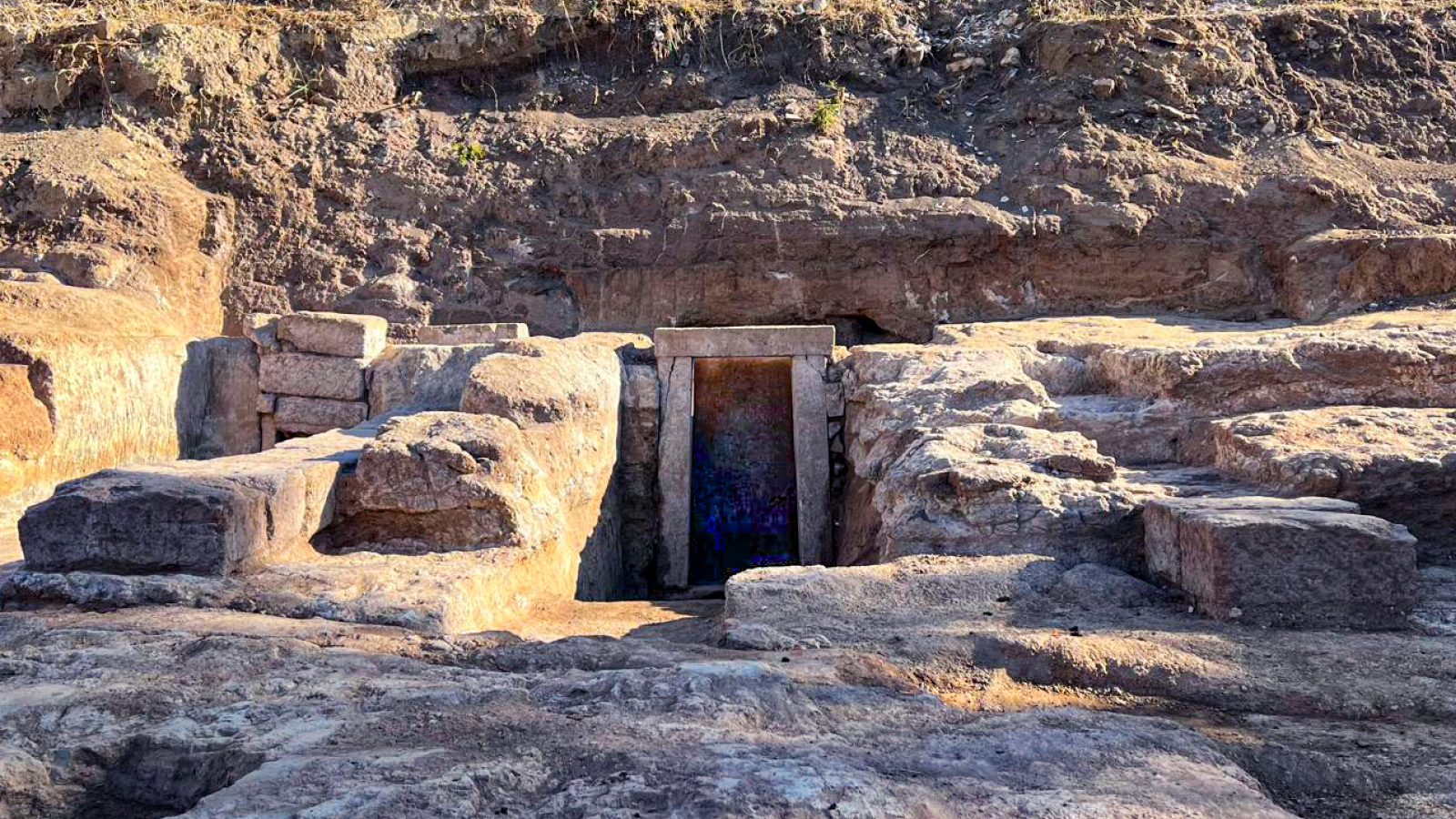

Horse whipper

McGreevy and his colleague David Evans enlisted the help of experienced "stewards of racing" — officials charged with judging jockeys' adherence to Australia's racing rules, including those limiting the use of whips. The stewards viewed five recorded thoroughbred races and counted whip strikes on 48 animals during the last 600 meters (656 yards). Electronic sensors in the horses' saddle blankets recorded the animals' times and their places at the finish line.

Through a statistical analysis of the data, the researchers found, rather predictably, that jockeys began whipping their horses in the second-to-last leg of the race, between 400 and 200 meters (438 and 219 yards) from the finish line, and they whipped the animals most during the final leg, when the horses were tired and slowing down.

But by the time the whipping started, McGreevy said, whether or not the horse would finish among the first three was usually already settled.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"A horse's performance before the final 400 meters, when it wasn't being whipped, was the strongest predictor of its racing success," McGreevy told LiveScience. "The highest speeds in these horses were achieved when they weren't being whipped."

Hard to justify

Horsewhips are often called feather dusters, ticklers, encouragers or persuaders, but there's no question in McGreevy's mind that they can inflict pain and injury — even the padded models now widely used in the United States and mandated in Australia.

"Whipping horses, especially when they're fatigued, is very difficult to justify under an ethical framework, especially when this is all being done in the name of sport," said McGreevy, an avid horseman himself. "A top-performance horse really needs great genetics, great preparation and great horsemanship, and that's what will get it into the right position to clinch the race."

McGreevy said he has preliminary data showing that apprentice jockeys tend to whip their horses three times more often than seasoned jockeys do, further suggesting that the technique’s effectiveness leaves something to be desired. "If it's such a marvelous tool, why are the seasoned veterans, the expert practitioners, using less of it?" McGreevy said.

As to whether funding by a group opposed to the use of whips in horse racing could have compromised the results, McGreevy's response was adamant. "The RSPCA want more information about whip use, and they're entitled to pay for it," he said. "The funders had no role in the study design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript."

Racers react

Whether whipping should be permitted is a controversy in Australia. After the paper appeared online Jan. 27 in the journal PLoS One, Australian newspapers reported that many of the nation's jockeys, trainers and horse owners "scoffed" at the research.

Some in the U.S. racing industry also objected to the paper's conclusion that whipping doesn't affect race outcome. While praising the study for opening the scientific dialogue on the issue, Scott Palmer, chairman of the American Association of Equine Practitioners' racing committee, questioned whether the study examined enough horses in enough races to be statistically significant.

Palmer, a racehorse veterinarian in Millstone, N.J., added that the study wasn't set up to determine whether the whip influences how a racehorse performs. To do that, he said, the researchers would have needed to set up trials comparing how horses perform with and without whips under a fixed set of racing conditions.

Palmer agreed with McGreevy's and Evans' finding that the whip can't motivate a horse to overcome its fatigue in the last legs of a race, something that he says is common knowledge. "But that doesn't mean that it's futile," Palmer said, adding, "You can't answer that question with this study."

In an e-mailed response to the study, an attorney with the Jockeys' Guild, an advocacy group for jockeys based in Nicholasville, Ky., also expressed reservations about the study's design and questioned whether it could be objective, considering it was underwritten by RSPCA Australia.

Attorney Mindy Coleman asserted that the rules governing whip use on U.S. tracks are sufficiently restrictive to ensure horses' welfare, and that jockeys need their whips to safely control their horses.

"There are currently approximately 60 jockeys in the U.S. who have been permanently disabled as a result of accidents on the racetrack. Without riding crops, that number would be much higher," Coleman wrote.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus