Most Ancient Child Unearthed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

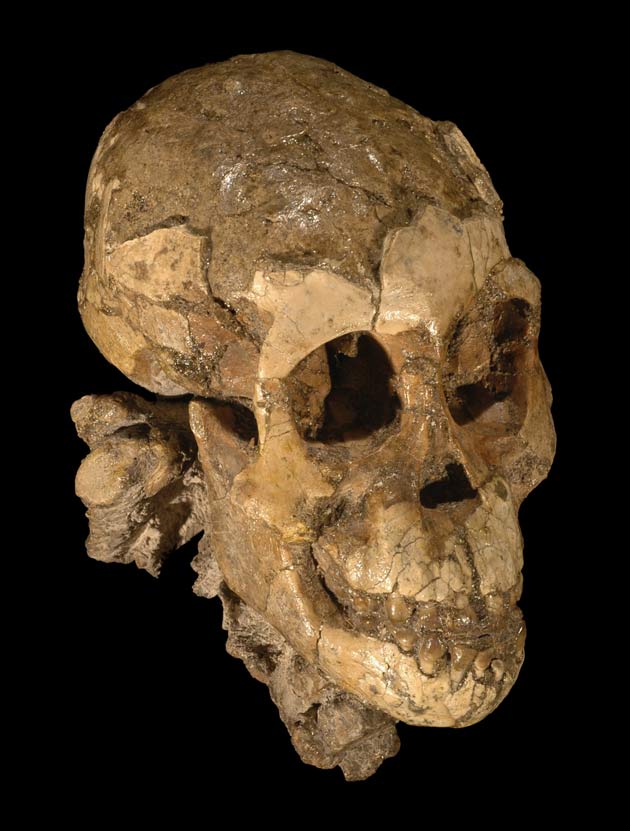

Scientists have unearthed the oldest child ever discovered—the fossil remains of what appears to be a girl dating back 3.3 million years.

The remarkably complete skeleton, of a child no more than three years old, offers new clues on how the early ancestors of humans blurred the line between us and the other great apes. While the child from the waist down is similar to upright walkers like humans, her upper body is surprisingly apelike, including curved finger bones almost as long as a chimp's, suited for scrambling up trees.

The girl belongs to the species Australopithecus afarensis, which is widely believed to be the ancestor of the genus Homo. This includes our own species, Homo sapiens.

Face peers out

The skeleton was found in badlands of the Afar depression in northeastern Ethiopia, where paleoanthropologist Zeresenay Alemseged at the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Leipzig, Germany, first led his colleagues in 1999. Extreme heat, flash floods, malaria, wild beasts and occasional shootouts plague this region, but it also has a rich history of human fossil discoveries.

Expedition member Tilahun Gebreselassie was the first to see the baby's tiny face peering out from a dusty slope, under a scorching sun in December 2000. Excavation revealed a bundle of bones no bigger than a cantaloupe.

It has taken five years so far to carefully etch away the sandstone—almost grain by grain—that the delicate, tiny bones were embedded in.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

A great flood

The layers of earth the skeleton was found in revealed the ancient Awash River apparently rapidly buried the baby in pebbles and sand during a flood, which possibly was the infant's cause of death. The region she lived apparently was a river delta rich in catfish, freshwater shellfish, crocodiles, hippos and giant tortoises, interspersed with otters and bush pigs. Woods nearby held impalas, and open grasslands held relatives of elephants, rhinos and wildebeests.

The pelvis, the lower part of the back and part of the limbs of the skeleton are missing, but much remains. This includes the whole skull, nearly the entire torso, the vertebrae down to the lower back, and all but two of the teeth, which X-rays showed included adult teeth still in the jaw that have not erupted yet.

This skeleton for the first time shows what an Australopithecus afarensis child looked like. This has yielded clues to how "our earliest ancestors grew their brains," said researcher Fred Spoor of University College London.

The infant's brain size is estimated at 330 cubic centimeters. This is not much different from that of a similarly aged chimp. However, when compared to adults of her species, she had formed only between 63 and 88 percent of her adult brain size. This is relatively slow brain growth compared to chimps, which by three years of age have formed more than 90 percent of the brain. This rate of brain growth is actually slightly closer to that of humans, possibly pointing to an early shift in human evolution.

Gorilla shoulders

Also found were skeletal parts that shed light on little known or unknown aspects of the origins of humanity. This includes the shoulder blades and the tongue or hyoid bone.

The shoulder blades resemble those of a young gorilla, suggesting she could climb trees. Evidence supporting a life in the trees is found in her chimp-like fingers and in the semicircular canals of her inner ear. These canals are filled with liquid and are crucial to keeping balance. In humans, two of these three canals are enlarged, to help maintance balance while upright. The skeleton's canals are more like those of chimpanzees than us.

The hyoid bone reflects how the voice box is built, thus revealing hints about the evolution of human speech. The girl's hyoid is different from that of humans and similar to those of the other great apes.

The skeleton is like humans in that it lacks opposable big toes, which baby chimps use to grip their mothers with their hands and toes, allowing the mother to forage, escape from danger and travel while keeping the baby close. This means the girl the scientists discovered probably had to be carried, limiting her mother's ability to care for herself and possibly making her dependent on her mate and social bonds with a larger group for protection and food.

The scientists reported their findings in the Sept. 21 issue of the journal Nature.

- Top 10 Missing Links

- Skull of 'Missing Link' Human Ancestor Found In Ethiopia

- Early Man Was Hunted by Birds

- Human Evolution Timeline

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus