Sound Pulses Exceed Speed of Light

A group of high school and college teachers and students has transmitted sound pulses faster than light travels—at least according to one understanding of the speed of light.

The results conform to Einstein's theory of relativity, so don't expect this research to lead to sound-propelled spaceships that fly faster than light. Still, the work could help spur research that boosts the speed of electrical and other signals higher than before.

The standard metric for the speed of light is that of light traveling in vacuum. This constant, known as c, is roughly 186,000 miles per second, or roughly one million times the speed of sound in air. According to Einstein's work, matter and signals cannot travel faster than c.

PVC science

However, physicist William Robertson at Middle Tennessee State University in Murfreesboro, along with a high school teacher, two college students and two high school students, managed to, depending on how you look at it, transmit sound pulses faster than c using little more than a plastic plumbing pipe and a computer's sound card.

"This experiment is truly basement science," Robertson told LiveScience.

The key to understanding their results, reported online Jan. 2 in the journal Applied Physics Letters, is envisioning every pulse of sound or light as a group of intermingled waves. This pulse rises and falls with energy over space, with a peak of strength in the middle.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Robertson and his colleagues transmitted sound pulses from the sound card through a loop made from PVC plumbing pipe and connectors from a hardware store. This loop split up and then recombined the tiny waves making up each pulse.

This led to a curious result. When looking at a pulse that entered and then exited the pipe, before the peak of the entering pulse even got into the pipe, the peak of the exiting pulse had already left the pipe.

If the velocities of each of the waves making up a sound pulse in this setup are taken together, the "group velocity" of the pulse exceeded c.

"I believe that this is the first experimental demonstration of sound going faster than light," Robertson said. Past research has proven it possible to transmit electrical and even light pulses with group velocities exceeding c.

Common thing?

Robertson explained this faster-than-light acoustic effect is likely commonplace but imperceptible.

"The loop filter that we used splits and then recombines sound along two unequal length paths," he said. "Such 'split-path' interference occurs frequently in the everyday world."

For example: "When a sound source is located near a hard wall, some sound reaches the listener directly from the source whereas some sound travels the longer path that bounces the sound off the wall. The sounds recombine at the listener," Robertson said. However, the weakness of the signals and the fact that any resultant differences in timing are very slight "mean that we would never be able to hear this effect."

None of the individual waves making up the sound pulses traveled faster than c. In other words, Einstein's theory of relativity was preserved. This means one could not, for instance, shout a message faster than light.

Still, this research might have engineering applications. Robertson explained that although it is not possible to send information faster than light, it seems these techniques could make it possible to route slower-than-light signals in electronic circuits faster than before.

- Life's Little Mysteries

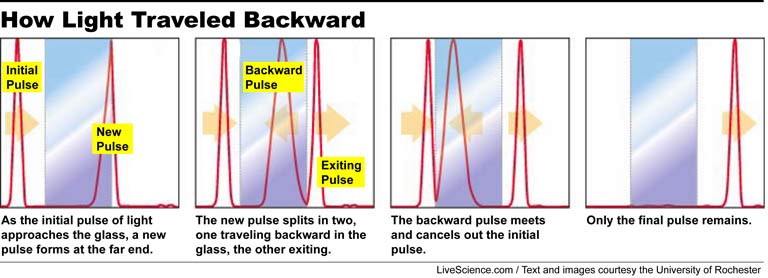

- Light Travels Backward and Faster than Light

- Scientists Question Nature's Fundamental Laws

- Scientists Mess with the Speed of Light

- The Biggest Popular Myths

In an unrelated previous experiment, Robert Boyd at the University of Rochester used similar principles to make pulses of light travel backward and faster than c.

See a graphic or animation

or read the story.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus