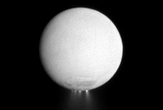

The mysterious icy jets erupting from Saturn's moon Enceladus may have their roots in a bubbly "Perrier ocean" flowing beneath the moon's frozen surface, a new study finds.

This salty subsurface sea could feed violent geysers on Enceladus, supplying them with water, gas, dust and heat before sinking back to the dark depths.

"The realization that there's a circulation system inside of Enceladus is something that's a new way of thinking," Dennis Matson, a researcher with NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory, told reporters Monday (Oct. 4). "But as you know, Enceladus has unique properties." [New photo of Enceladus geysers.]

Matson discussed the Enceladus find at the American Astronomical Society's Division of Planetary Sciences meeting in Pasadena, Calif.

Mysterious geysers on an icy world

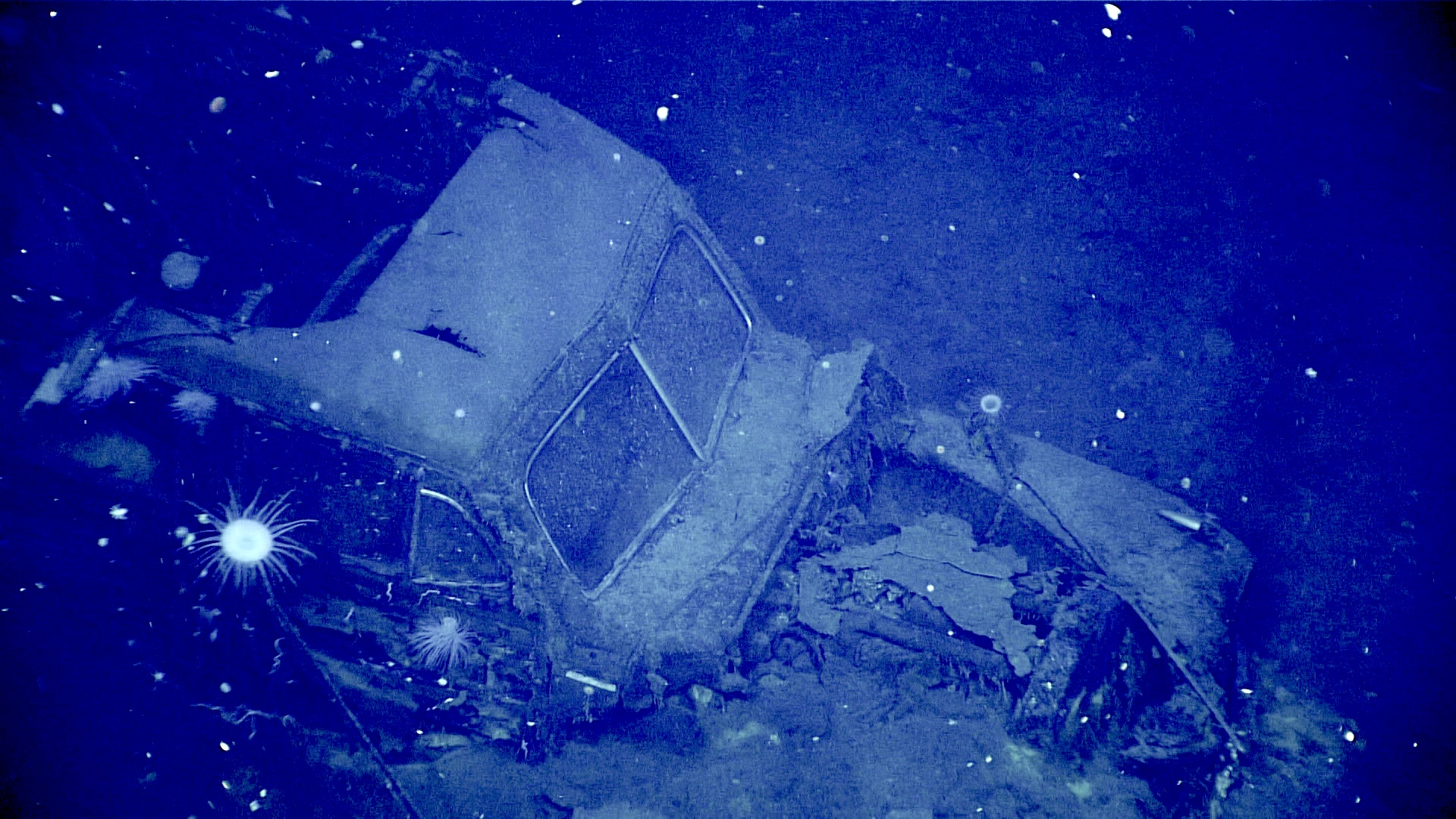

The ice geysers of Enceladus were first spotted in 2005 by NASA's Cassini spacecraft, which revealed jets of icy particles erupting from the moon's southern polar region. Enceladus is Saturn's sixth-largest moon.

The discovery jolted many astronomers — as did other evidence of a hot spot around Enceladus' south pole — showing that the small, frozen and presumably dead moon is geologically active.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

More recent observations from Cassini have shown that the geysers are associated with Enceladus' "tiger stripes" — huge fissures in the moon's ice-covered surface.

Cassini has also found that the geysers contain water vapor, sodium salts, potassium salts and carbonates, suggesting that a sea of liquid water flows beneath the moon's icy crust.

The probe's observations revealed huge amounts of heat flowing through the tiger stripe region — about five times more heat per unit area than flows through Earth's geologic hot spot, Yellowstone National Park, scientists have said.

Such finds further intrigued scientists, but they didn't fully explain the fundamental nature of Enceladus' geysers or what was feeding them. The new results could help flesh out that explanation.

A heat-transferring sea

Matson and his colleagues came up with a computer model that accommodates much of what is known about the geysers of Enceladus. Their findings support the supposition that a salty sea flows under the moon's surface.

This ocean has gases dissolved in it, the theory goes. As the seawater flows up to and through the tiger stripe fissures, its pressure drops and the gases bubble up, Matson said — making the ocean fizzy, like Perrier. The relatively warm water and expanding gas feed the jets.

When the bubbles pop, they throw off a fine spray that contains salt and other materials, which Cassini spotted in Enceladus' plumes. Then the seawater, having dumped much of its warmth on the moon's surface ice, cools and sinks back through cracks, rejoining the ocean and its heat-transferring circulation system.

"Until now, how you got so much heat out was a big, big problem," Matson said.

The model doesn't require much dissolved gas in the "Perrier ocean" to work — only 1 or 2 percent, researchers said. And it explains the geyser phenomenon pretty well, including the ultimate source of some of the materials ejected in the plumes.

"A liquid ocean would be in contact with the rocky core" of Enceladus, said Linda Spilker of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Cassini deputy project scientist. As it flows past that core, the sea could pick up elements like sodium and potassium, she added.