Wrong Spoon Size Can Cause Medicine Mistakes

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

When pouring out doses of cold medicine, you may want to ditch the kitchen spoon for a more exact measuring device, a new study suggests. Depending on the spoon’s size, people tend to pour too little or too much.

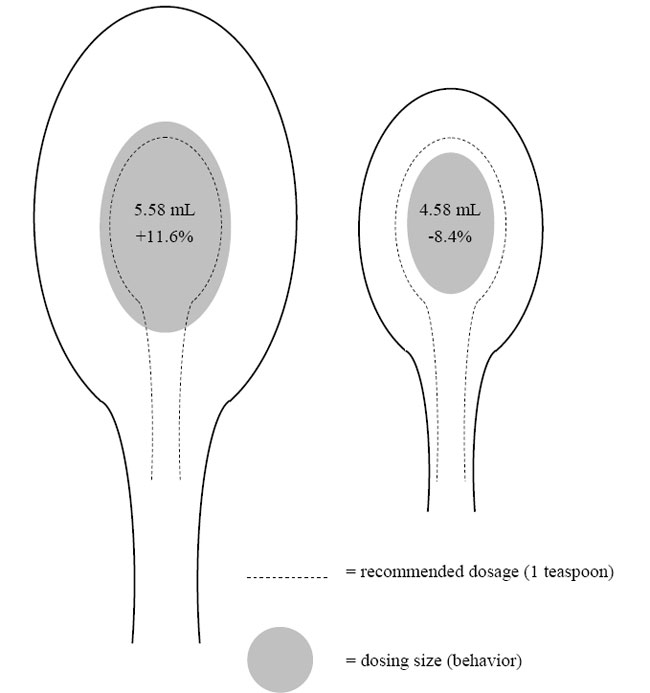

The study involved 195 university students who were asked to pour a teaspoon (5 mL) of liquid medicine into a medium-sized spoon and a large spoon. To give them a better understanding of the volume of a teaspoon, the researchers had students measure out the medicine first in an actual teaspoon before trying it out in the other two spoons.

Participants poured an average of 4.58 mL, or about 8 percent less than prescribed, into the medium spoon, and 5.58 mL, or nearly 12 percent more for the larger spoon. Even so, the students indicated above-average confidence that their pouring was accurate.

"Twelve percent more may not sound like a lot, but this goes on every four to eight hours, for up to four days," said lead researcher Brian Wansink, director of the Cornell Food and Brand Lab. "So it really adds up — to the point of ineffectiveness or even danger."

The participants were also in atypical conditions, pouring cold medicine in a well-lit room in the middle of the day. "But in the middle of night, when you're fatigued, feeling miserable or in a rush because a child is crying, the probability of error is undoubtedly much greater," he said.

Essentially, an optical illusion came into play called the size-contrast effect, in which we use one object as a reference point from which to measure a nearby object. For instance, an average-height guy standing next to an extremely tall friend would appear far shorter than if he stood next to a more petite man.

"That's what's going on with pouring the medicine. One teaspoon into a three-ounce spoon looks like nothing, so you pour more," Wansink told LiveScience. That led to overdosing. The opposite effect plagued the medium-sized spoon.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

About 70 percent of us grab silverware spoons to take liquid medicine, according to the Mayo Clinic. With the new study results, Wansink recommends instead that consumers use a measuring cap, dosing spoon, measuring dropper or a dosing syringe.

The study is detailed in the Jan. 5 issue of the journal Annals of Internal Medicine.

- The Most Popular Myths

- 7 Solid Health Tips That No Longer Apply

- Top 10 Worst Hereditary Conditions

Jeanna Bryner is managing editor of Scientific American. Previously she was editor in chief of Live Science and, prior to that, an editor at Scholastic's Science World magazine. Bryner has an English degree from Salisbury University, a master's degree in biogeochemistry and environmental sciences from the University of Maryland and a graduate science journalism degree from New York University. She has worked as a biologist in Florida, where she monitored wetlands and did field surveys for endangered species, including the gorgeous Florida Scrub Jay. She also received an ocean sciences journalism fellowship from the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. She is a firm believer that science is for everyone and that just about everything can be viewed through the lens of science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus