Global Disaster Hotspots: Who Gets Pummeled

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

The human impact of a natural catastrophe depends greatly on where it happens, disaster officials have long known. In a soon-to-be-published report, scientists have mapped out some of the worst places to live when Nature shows the ugly side of her face.

The maps and analysis were prepared by the Earth Institute at Columbia University for the World Bank, which expects to publish them sometime this winter. The report is designed as a guide for how international investments should be made and a tool for battling calamity before it strikes.

The researchers compiled statistics from the last two decades on natural disasters in three categories: geophysical (earthquakes, volcanoes, and landslides), hydro (floods and hurricanes) and drought.

Based on these factors, they mapped out hot spots of risk.

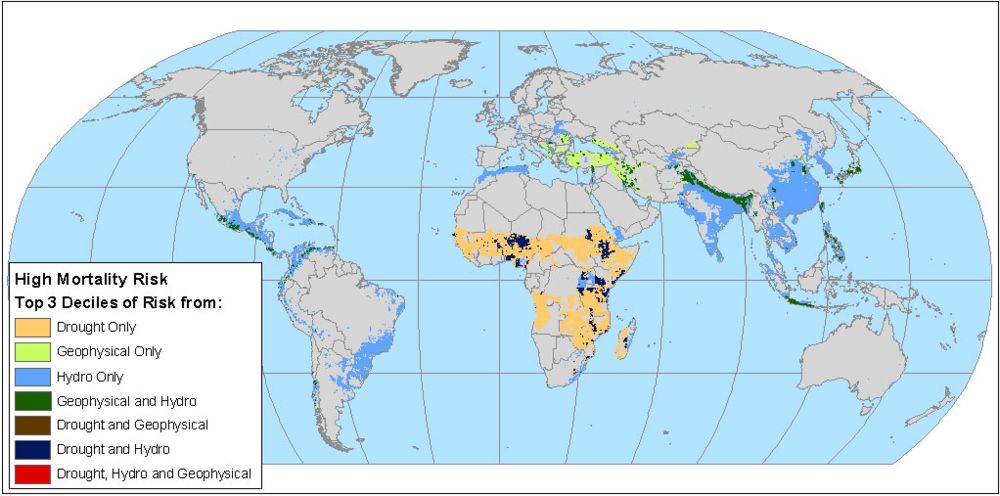

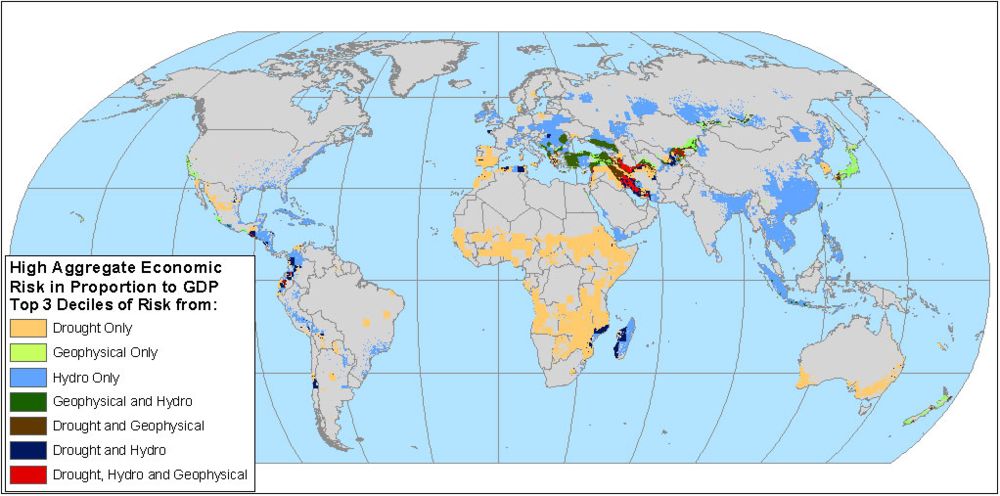

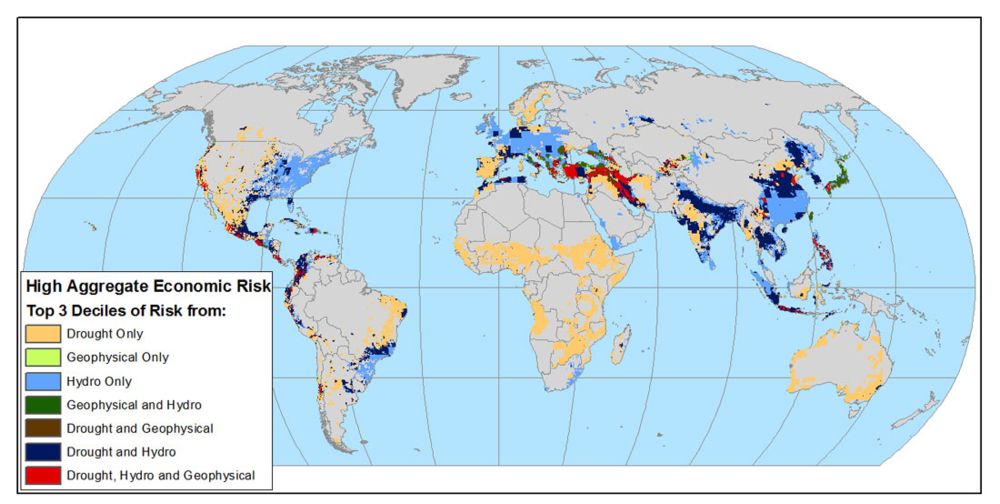

Hotspots based on ...

... mortality risks

... total economic loss risks

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

... economic loss risks as a proportion of GDP per unit area

Maps courtesy the Earth Institute at Columbia University

"The notable feature of the maps is that there are small countries that get pummeled," the Earth Institute's Arthur Lerner-Lam told LiveScience. Places like Honduras, Guatemala, and the Philippines are some of the riskiest.

Part of this has to do with geography. Central America, for example, is an area of high tectonic activity, which results in many volcanoes and earthquakes. It is also in the path of tropical storms.

"If a geologist were to put a country somewhere, this might be one of the last places," Lerner-Lam said of Central America.

But there are many reasons why people choose to live in dangerous areas. "Lots of people farm on volcanic soil because it's fertile," Lerner-Lam said in a telephone interview prior to the Asian disaster. And coastlines were, and continue to be, important centers for trade.

Beyond geography, however, developing countries have a harder time preparing for and recovering from disasters, as was evidenced by the lack of warning for December's tsunami in Asia and the agonizing days people waited for relief crews.

"Poorer people are hit disproportionately by hazards," Lerner-Lam said.

Part of the problem is that poorer nations get stuck in the "recovery trap." They spend so much of their resources rebuilding after the last disaster that they are not ready for the next one. This is not true in well-off countries like Japan and Italy, which comparatively suffer a lot of economic damage, but whose economies "can absorb the brunt of these disasters," Lerner-Lam said.

The risks in the new report were calculated based on the number of deaths, the cost, and the cost as a percentage of the economic output, or Gross Domestic Product (GDP), of that location. The maps indicate hotspots, which are areas in the top 30 percent of risk for a given indicator.

The goal of the new maps is to help investors make smart choices for sustainable development. A good example is earthquake-prone Istanbul, Turkey, where the effort is to construct buildings that are less vulnerable.

By spending a little more money to make something earthquake-resistant, Lerner-Lam said, "we reduce the loss of life and get a better return on the building because it doesn't fall down."

A little preventative medicine could impact the movement of money around the globe. World Bank data indicates that emergency loans and reallocation of existing loans for disaster reconstruction from 1980 to 2003 totaled $14.4 billion, with $12 billion going to disaster hotspot countries.

"This tells us that we need to work to reduce the vulnerability of these developing countries to natural disasters as part of any poverty reduction strategy," said the Earth Institute's Robert Chen.

- The Odds of Dying

- Nature's Wrath: Global Deaths and Costs Swell

- Forecast for 2005: Another Busy Hurricane Season

- 2004: A Record Year for Tornadoes

Tsunami Special Report

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus