U.S. and Europe 'Outsource' Greenhouse Gas Emissions

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

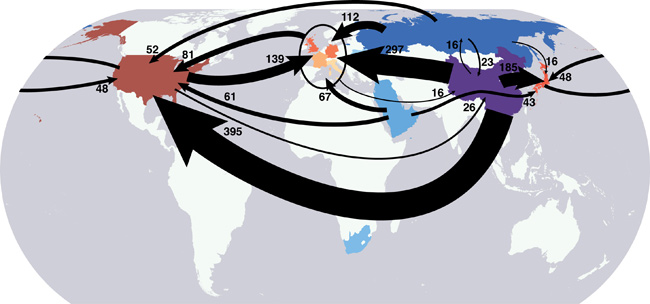

The United States and other developed countries are effectively "outsourcing" their greenhouse gas pollution to developing countries. One-third of carbon dioxide emissions associated with the goods and services consumed in First World countries is actually being emitted outside the borders of those nations, mostly in the developing world, a new study finds.

The study, detailed in the March 8 issue of the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, marks the first look at the "importing" and "exporting" of greenhouse gas emissions and could provide a useful means of surmounting stumbling blocks to international agreements on climate change, the authors of the study say.

Growth in carbon dioxide emissions accelerated over the last decade, much of which has been attributed to the explosion of industry in developing countries, particularly India and China, and the use of less clean technologies in those places as compared to much of the First World.

But this picture of greenhouse gas emissions growth isn't as straightforward as it might appear, Carnegie Institution scientists Ken Caldeira and Steven Davis say, because a good chunk of those developing-country emissions come from the production of goods (anything from cars to clothes to rubber and plastic) that are actually consumed in First World countries, such as the United States, Japan and the states of the European Union.

Effectively, this situation results in the importing and exporting of carbon dioxide emissions between countries

To see just how much carbon dioxide was being imported and exported, Davis and Caldeira looked at 2004 global economic data (the most recent year with complete information) from 113 countries, or regions, and 57 sectors of industry.

"Instead of looking at carbon dioxide emissions only in terms of what is released inside our borders, we also looked at the amount of carbon dioxide released during production of the things that we consume," Caldeira said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Here's what they found:

- In 2004, 23 percent of global carbon dioxide emissions — or 6.8 billion tons (6.2 billion metric tonnes) of carbon dioxide — were traded internationally, mostly exported from emerging markets and imported to developed countries.

- In some wealthy countries, such as Switzerland, Sweden, Austria, the United Kingdom and France, more than 30 percent of emissions from goods and services consumed there were made elsewhere and imported. Net imports per person for many Europeans were equal to more than 4 tons of carbon dioxide in 2004.

- In the United States, 10.8 percent of consumption-based emissions were imported, working out to around 2.4 tons of carbon dioxide per person.

- On the other side of the equation, 22.5 percent of the emissions produced in China in 2004 were exported elsewhere.

- China is the largest exporter of emissions, followed by Russia, the Middle East, South Africa, Ukraine and India.

- The primary importers of emissions are the United States, Japan, the United Kingdom, Germany, France and Italy.

While the location of carbon dioxide makes no difference to the global climate system, the findings could help to answer the question of who is responsible for lowering emissions to combat climate change.

Many developing countries, including China and India, have resisted global agreements on reducing emissions on the grounds that First World countries got to where they are through two centuries of fossil fuel burning. And forcing developing nations to curtail their industry would prevent them from growing and reaching First World standards, they've argued.

By looking at emissions in terms of imports and exports, and placing the burden of reduction on the people ultimately responsible for them – the first world consumers of all those goods and services made elsewhere – the debate over who should be reducing emissions could be reframed, Caldeira and Davis suggest.

"To the extent that constraints on developing countries' emissions are the major impediment to effective international climate policy, allocating responsibility for some portion of these emissions to final consumers elsewhere may represent an opportunity for compromise," Davis said.

- Top 10 Emerging Environmental Technologies

- Quiz: What's Your Environmental Footprint?

- Global Warming News and Information

Andrea Thompson is an associate editor at Scientific American, where she covers sustainability, energy and the environment. Prior to that, she was a senior writer covering climate science at Climate Central and a reporter and editor at Live Science, where she primarily covered Earth science and the environment. She holds a graduate degree in science health and environmental reporting from New York University, as well as a bachelor of science and and masters of science in atmospheric chemistry from the Georgia Institute of Technology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus