Life at Sea: An Oceanographer's Adventure

This Behind the Scenes article was provided to LiveScience in partnership with the National Science Foundation.

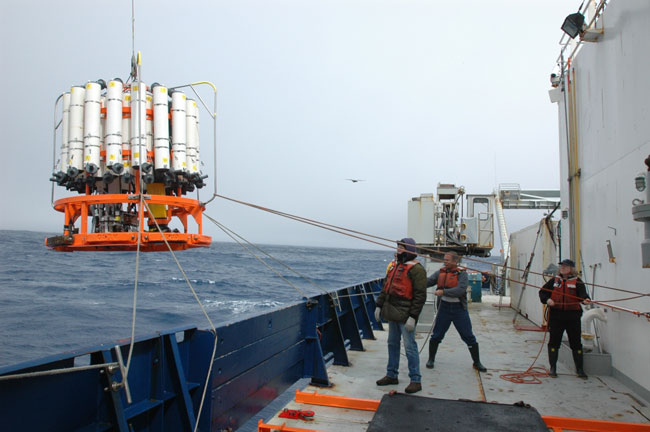

Life at sea is very different from life on land . . . Or is it? It may be hard to imagine spending weeks at a time at sea, but for many in our ocean-going team made up of scientists, technicians and students, living and working at sea is an important part of our careers. Whether or not we are hardy sea-going adventurers, we often spend at least several weeks—even months—at sea where we can collect and analyze data in the field. Scientists are eager to do real-time oceanography, studies that involve data collected from experiments at sea. Technicians enjoy the chance to get out of their land-based laboratories and out onto the open waters. And students experience the ocean in a much more genuine way than any textbook can provide. To this team, our research vessel is not only their laboratory at sea, but it is also our home and office, full of all the functions of daily life. This particular cruise is part of an National Science Foundation-funded effort called the Climate Variability and Predictability program, or CLIVAR. Cruises travel along pre-selected routes, or tracks, about once every ten years collecting climate data from the seas. The data on temperature and salinity will show us how the ocean, and the climate, have changed since 1994. The CLIVAR cruises usually traverse areas that are not often visited, so there is a sense of adventure and the vastness of the ocean contributes to the sense of exploration – one feels as if they are an early explorer on the high seas. So what is life like on board our research vessel, the Roger Revelle? One major difference between life on land and life at sea is that the ship is constantly moving. In rough seas, we walk around like drunken sailors, holding onto the ubiquitous hand rails. Everything must be secured so that it doesn’t fly across the room – even people! Chairs are often lashed to the desks, computers are tied down, and special mats must be used on tables in the mess hall. As long as it’s not something important, it can be funny to watch someone’s book or paper go flying across the room. Another difference is that the typical oceanographer must be ready for work by noon or midnight, depending on which of the two 12-hour watches they are assigned. Because the ship is constantly traveling, it might reach a station at any time of the day. Many people need to be awake to deploy the instruments, take samples, and process them in the laboratory. When Jim Swift, the Chief Scientist, was asked why the crew works 12 hours straight, his answer was simply, “Because they like 12 hours off!” – although the shifts become routine after awhile. Life at sea, although it has some differences, often mirrors life on land. The community of scientists, crew, students and technicians makes living and working at sea exciting and enjoyable. If there is one trait common to this diverse group, it lies in participating in a shared, intensive endeavor, and enjoying, at least for a month or so, new associates and old friends.

- Image Gallery: Underwater Explorers

- Image Gallery: Rich Life Under the Sea

- All About the Sea

Editor's Note: This research was supported by the National Science Foundation (NSF), the federal agency charged with funding basic research and education across all fields of science and engineering.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.