Neanderthals' Big Noses Get an Airy Explanation

In the human family tree, Neanderthals are our closest extinct relatives, and they looked a lot like modern humans. But one defining difference was a distinctive skull shape, with the middle part of their faces pushed forward dramatically — far more so than in their human cousins.

Scientists have argued about what might have shaped Neanderthal skulls, with some suggesting that this adaptation meant greater biting power, and others proposing that it could have been due to an enhanced airway.

Now, thanks to digital 3D modeling, a new study has answers. And they point to the "enhanced airway" hypothesis. [In Photos: Neanderthal Burials Uncovered]

Humans and Neanderthals co-existed on Earth for about 5,000 years, until Neanderthals went extinct about 40,000 years ago. Both groups shared a number of physical features, including an oddball bone called the hyoid bone that's linked to speech; a pelvis built for upright walking; and larger skulls to accommodate bigger brains than their more distant primate relatives.

Neanderthals also had certain skull features that modern humans don't — a heavier brow and weaker chin — that recall earlier ancestors in the human lineage. But their protruding faces were unique, setting them apart "not just from us, but from their ancestors, too," the study's lead author, Stephen Wroe, director of the Function, Evolution and Anatomy Research (FEAR) Lab at the University of New England in Australia, said in a statement.

Researchers have advanced several explanations for this specialization. One hypothesis, partly based on evidence from Neanderthal tooth wear, hinted at unusually powerful biting that would have applied more force to the front teeth, the scientists wrote in the study.

However, other researchers argued that Neanderthal face shape was linked to a modified airway that helped them survive in the chilly, dry climate of the last Ice Age during the Pleistocene epoch (about 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago).

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

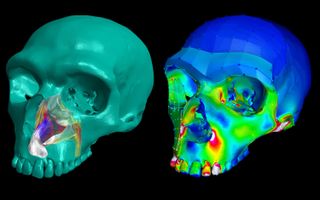

To test these ideas, scientists imaged Neanderthal skulls using X-ray computed tomography (CT) scans and created 3D digital models from those scans. By working with digital models, the scientists could "crash-test" the skulls without the risk of damaging them, Wroe told Live Science in an email.

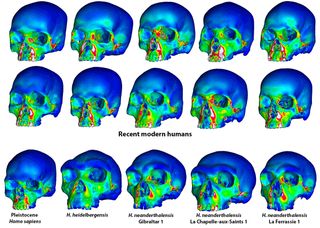

First, they used the models to simulate Neanderthal bite force — the first study to do so. The researchers compared the performance of their Neanderthal biter to models of skulls from modern humans, and from an earlier extinct human species, Homo heidelbergensis, which lived about 700,000 to 200,000 years ago, and they discovered that when it came to biting, Neanderthal performance wasn't such a big deal.

"We found that the Neanderthal skulls showed just as much strain when biting at the front teeth as did many modern humans — suggesting that they were no better adapted to perform this behaviour than we are," Wroe said in the email.

Next, the scientists re-created the soft tissue of the skulls' nasal passages, and modeled the movement of air through the different cavities, Wroe told Live Science. Tests indicated that Neanderthals' nasal passages could heat up and humidify the air they were breathing more effectively than H. heidelbergensis — definitely a plus in a cold, dry climate — but not as efficiently as modern humans, the study authors reported.

But Neanderthals vastly outperformed both H. heidelbergensis and modern humans with the sheer quantity of air they could move quickly in and out of their lungs; in fact, a Neanderthal's breathing was likely almost twice as effective as a human's at pulling in air, according to the study.

To survive and thrive in an Ice Age landscape, Neanderthals may have needed lots of energy to regularly chase after large animal prey or just to keep warm — "Or it could be some combination of both," Wroe said in the statement.

"The take-home message from this is that the distinctive, projecting Neanderthal face is an adaptation linked with an extreme, high-energy lifestyle," he added.

The findings were published online today (April 3) in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology, and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works Magazine.

Most Popular