New Therapy Halts Rare Brain Disease Depicted in 'Lorenzo's Oil'

Doctors have successfully suppressed a rare brain disease that typically strikes young boys, by using a novel type of therapy that alters a patient's genes.

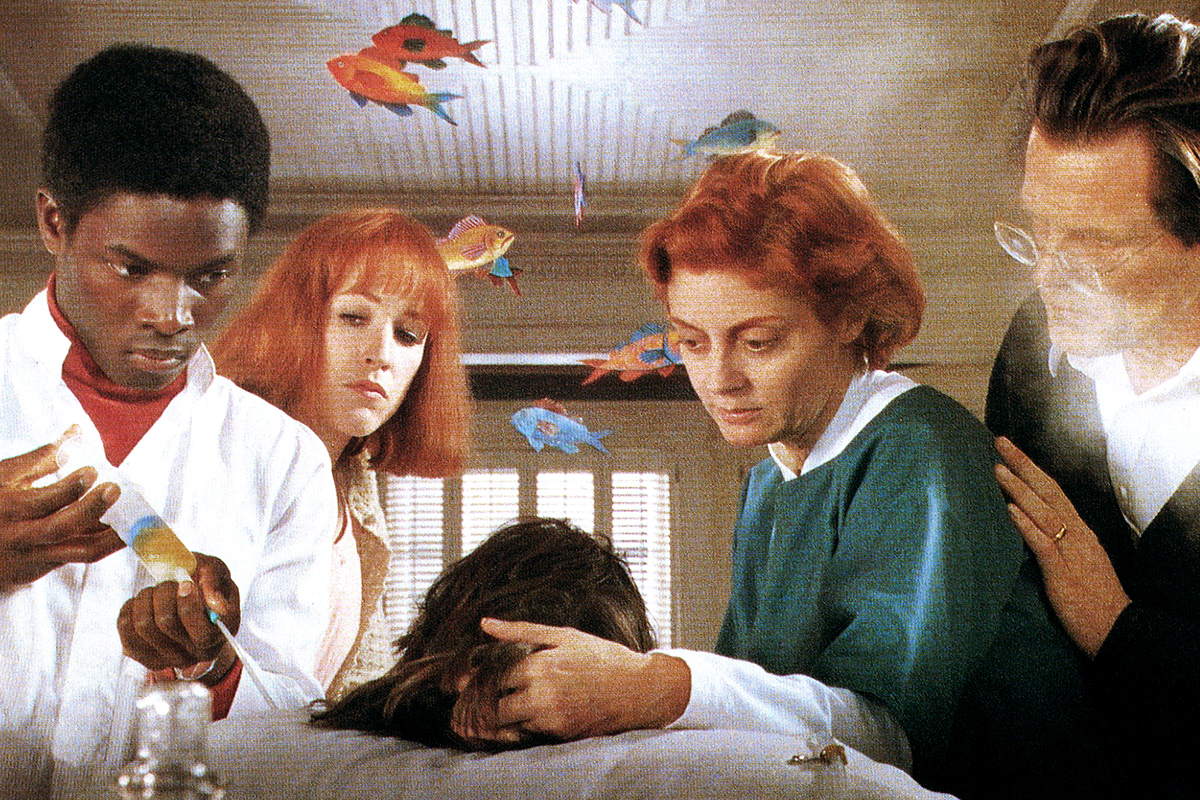

The disease, called adrenoleukodystrophy (ALD) is an extremely rare degenerative disorder that affects about 1 in 20,000 people worldwide, virtually all of whom are boys. One family's desperate search for a cure for ALD was depicted in the 1992 film "Lorenzo's Oil."

ALD occurs when an individual inherits a faulty copy of the ABCD1 gene. This faulty gene means that boys with ALD are unable to make a protein that helps break down certain fatty acids, causing their nerve cells to die and neurological function to rapidly deteriorate. Once children start showing symptoms, they quickly lose the ability to walk or talk, going from fully functioning kids in school to being dependent on feeding and breathing tubes within five to ten years of diagnosis. In the disease's most severe form, boys with cerebral ALD die before their 10th birthday. [7 Diseases You Can Learn About from a Genetic Test]

"It's a devastating disease," said co-lead study author Dr. Florian Eichler, a neurologist at Massachusetts General Hospital. "Unfortunately, when it is diagnosed after symptoms occur, it is often too late, and the wildfire of inflammation in the brain has already spread so far that we have trouble controlling it."

Currently, the only effective treatment for ALD is a bone-marrow transplant, Eichler told Live Science. But that requires a long, arduous wait for a compatible donor, and often results in complications such as graft-versus-host disease, in which the body attacks the transplant.

But with gene therapy, the risk of graft-versus-host disease is eliminated, because the boys can serve as their own cell donors, Eichler says.

In the new study, published online Oct. 4 in The New England Journal of Medicine, Eichler and his team treated 17 boys ages 17 or younger with a single dose of the experimental gene therapy. When the researchers followed up on the boys two years later, 15 were functioning without any major disability or progression of their disease. The other two had died, one from a worsening of the disease and the other from complications of a donor transplant he got after he withdrew from the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

For the gene therapy, the children had their own stem cells harvested from their blood rather than bone marrow. Then, scientists used a unique tool to infuse the cells in a lab with the healthy ABCD1 gene: a lentivirus made from a disabled form of HIV. The lentivirus acts as a "vector," carrying and inserting the healthy gene into the stem cell DNA.

"These vectors are kind of like living medicines," said Dr. David Williams, the chief scientific officer at Boston Children's Hospital and the senior author of the study. Once in the body, these altered blood stem cells constantly regenerate to keep treating the patient's disease. The advantage of using disabled HIV over other viral carriers is that HIV actually delivers the healthy gene more safely, without apparently altering any neighboring DNA, Williams told Live Science.

When the modified stem cells are transplanted back into the patient two months later, the cells multiply in the bone marrow and eventually find their way into the brain through the bloodstream. There, they replace microglial cells, breaking down fatty acids and supporting neurons to prevent any further brain damage from occurring.

"This is very exciting, not just for kids and families with adrenoleukodystrophy, but also as a breakthrough for other disorders that [affect] the brain,” said Amanda Bergner, a genetic counselor at Columbia University who was not involved in the study. Neurological disorders have traditionally been hard to target and treat because of how the brain is sealed off from the rest of the body, she said.

But the study's success has prompted the therapy maker and study sponsor — biotech company Bluebird Bio — to include an additional eight boys in the trial. Separate research is also focused on how boys receiving gene therapy fare compared to those who had bone-marrow transplants. And Bluebird Bio scientists, some of whom were also involved in the study, have indicated that they plan to pursue FDA approval for the therapy.

Only one gene therapy is FDA-approved in the U.S. — a leukemia treatment that received the go-ahead in August. A few others are undergoing clinical trials and some have won regulatory approval in Europe.

Fixing rare genetic diseases is impressive, but what remains to be seen is how long the benefits will last, how much the treatment will cost and how accessible it will be to those who need it, Bergner told Live Science. "It's a valuable step forward," she said. “But the next step is really going to be implementing programs that help detect ALD as early as possible and lowering barriers to the treatment so that it can be most effective."

Originally published on Live Science.