Extinct Giant Rodents' Family Tree Rewritten by New Fossil Finds

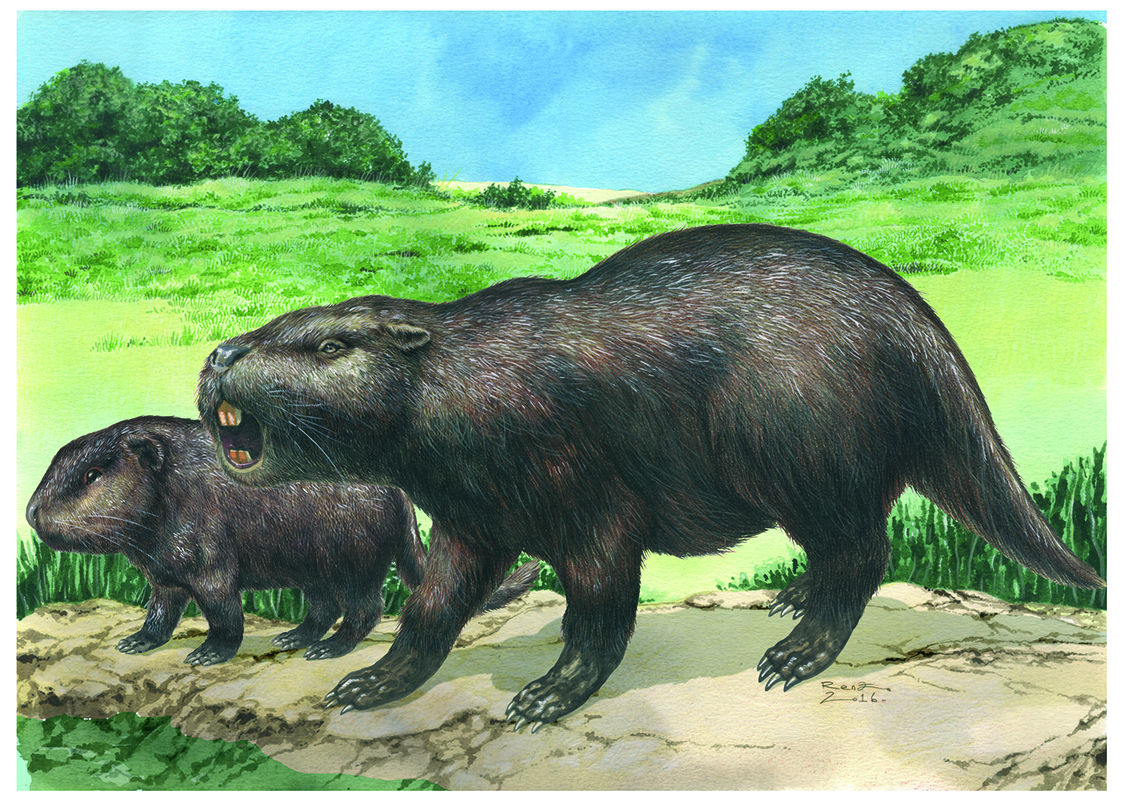

Scientists have found a near-complete skull and a jaw from a pair of giant rodents belonging to a group that lived millions of years ago in South America, and they say the fossils show that the extinct creatures weighed as much as 1 ton when fully grown.

These are the best-preserved fossils to date of this extinct group, which was previously known only by skull fragments and individual teeth, the scientists reported in a new study.

The new fossils of the two rodents — an adult and a juvenile — paint a more complete picture of the extinct and massive rat-like animals, the researchers said. For instance, the finds raise questions about how these giant rodents were classified within their genus, and hint that several species that were thought to be related may instead be a single species, the researchers wrote in the new study. [In Images: 'Field Guide' Showcases Bizarre and Magnificent Prehistoric Mammals]

A number of oversize rodent species roamed South America during the Miocene epoch, which lasted from about 23 million years ago to 5.3 million years ago, and some were downright gigantic. The largest rodent ever described, the enormous Josephoartigasia monesi, was roughly the size of a buffalo and had a bite force as powerful as a tiger's, according to a study published in February 2016 in the Journal of Anatomy.

However, most of these large-rodent lineages went extinct long ago, except for the capybara, a water-loving, web-footed rodent that can weigh as much as 174 lbs. (79 kilograms). Also known as "water hogs" and "masters of the grasses," capybaras are found in Central and South America — with the exception of one rogue individual that recently appeared in central California. (After several sightings, this capybara still remains at large.)

Fossils from the giant-rodent genus Isostylomys date back to the early 20th century, but the new finds from Uruguay's Camacho Formation, a site from the late Miocene epoch — about 12 million to 5 million years ago — are the most complete to date.

Skull and jawbones

Scientists uncovered a nearly intact adult skull and jawbone, as well as a juvenile jawbone containing all of its teeth. Both individuals represent the species Isostylomys laurillardi, which is thought to be nearly as large as J. monesi. The fossils' exceptional condition allowed scientists to compare tooth development between the adult and the juvenile, thus providing a new perspective on all other species in this genus, which had been described from more fragmentary fossil evidence.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The study authors found that the adult-tooth shape emerged fairly early in the rodent's development, growing larger as the animal matured. Then, they evaluated prior fossil finds by considering three possible tooth forms for I. laurillardi — prenatal, juvenile and adult — recognizing that adult-tooth forms could vary in size. The researchers' analysis determined that three known Isostylomys species were, in fact, one species — I. laurillardi.

"Our study shows how the world's largest fossil rodents grow," study lead author Andres Rinderknecht, a researcher in the Department of Paleontology at Uruguay's National Museum of Natural History, said in a statement.

The researchers concluded that, from a very young age, the giant rodents were very similar to the adults, Rinderknecht said. That conclusion led the research team to deduce that the vast majority of the prior hypotheses were wrong, he said.

The findings were published online Tuesday (Feb. 21) in the Journal of Systematic Palaeontology.

Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is an editor at Scholastic and a former Live Science channel editor and senior writer. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to Live Science she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in New York City. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post and How It Works. She is the author of the book "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind Control," published by Hopkins Press.