More US Teens May Be Facing Depression: Here's Why

Across the U.S., there's been an uptick in the percentage of teens who are having episodes of depression, a new report finds.

From 2013 to 2014, about one in nine teens in the United States had a major depressive episode, up from about one in 10 teens from 2012 to 2013, the researchers found. Psychologists define a major depressive episode as having symptoms of major depressive disorder — such as depressed mood or feelings of emptiness, hopelessness or irritability — that last for two weeks or more.

In the report, the researchers looked at data from the government's National Surveys on Drug Use and Health, in which adolescents ages 12 to 17 were asked about their drug use and mental health. The researchers focused on questions about symptoms the teens may have experienced in the past year that would signal an individual had experienced a major depressive episode. [8 Tips for Parents of Teens with Depression]

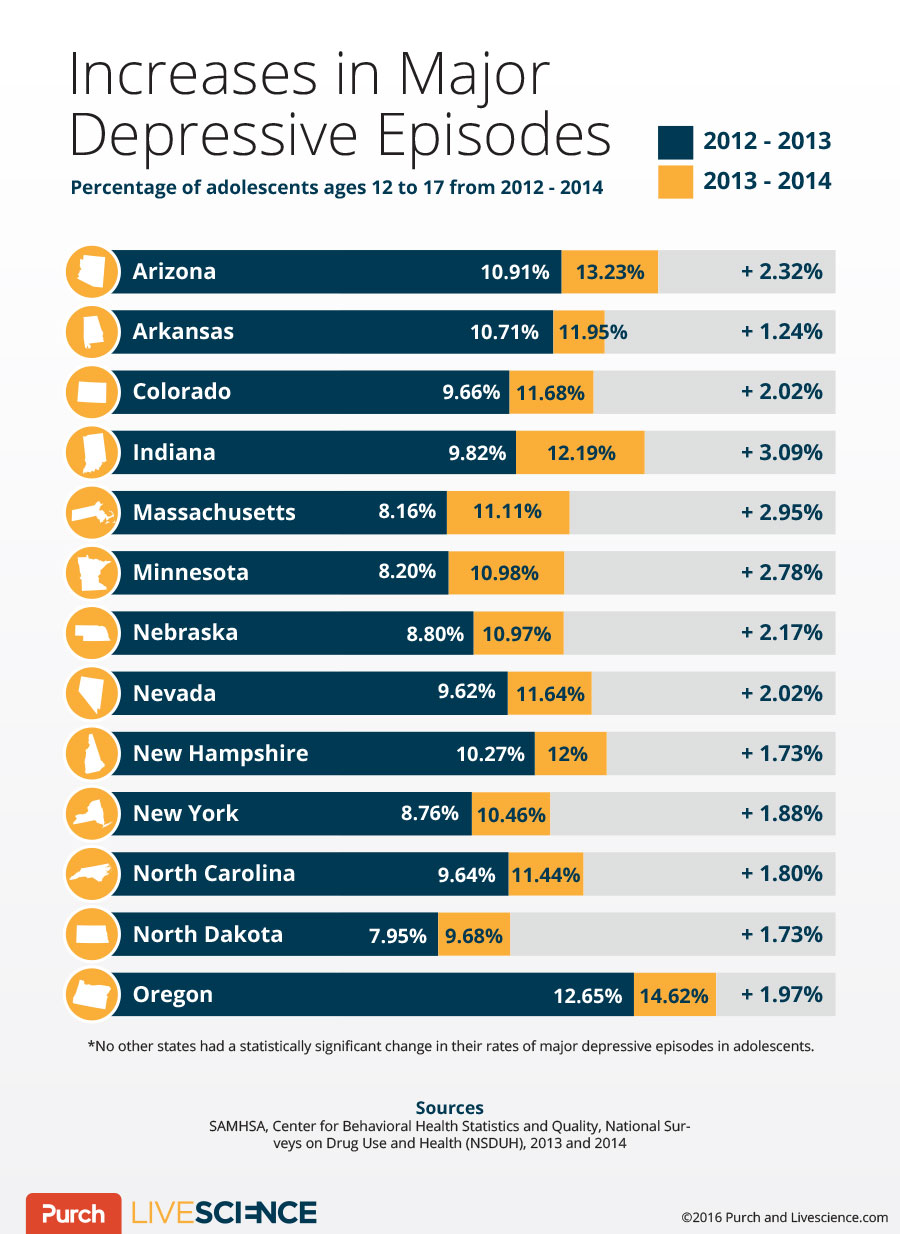

Overall, the national percentage of teens who had major depressive episodes in the 2013-2014 report was 11 percent, up from 9.9 percent in the 2012-2013 report, the researchers found.

It's unclear if these findings mean that rates will continue to go up, said Myrna Weissman, a professor of psychiatry at Columbia University in New York. To figure that out, you'd have to look at trends over a longer time, she said.

However, the findings are in line with what experts would expect: Depression is very common among adolescents, Weissman told Live Science.

The teens included in the study were right in the age range at which you'd expect symptoms of depression to first emerge, Weissman said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Ardesheer Talati, an assistant professor of clinical neurobiology in psychiatry at Columbia University and New York State Psychiatric Institute, agreed that one year isn't long enough to determine if rates are truly rising or if the reported increase is more of a blip.

However, three factors may explain the slight increase, Talati told Live Science.

First, increased awareness of mental illness could lead to more teens going to the doctor to be evaluated for depression. Or, in cases of younger adolescents, parents may pick up on changes in their kids' behavior, and bring them to the doctor, he said.

Second, there's a lot more pressure on teens than there was in the past, Talati said. These stressors — social, family and academic — may increase depression in teens, he said.

Finally, the way that depression is diagnosed has changed over time and has become more broad, Talati said. This means that more people will be diagnosed, he said.

Different rates in different states

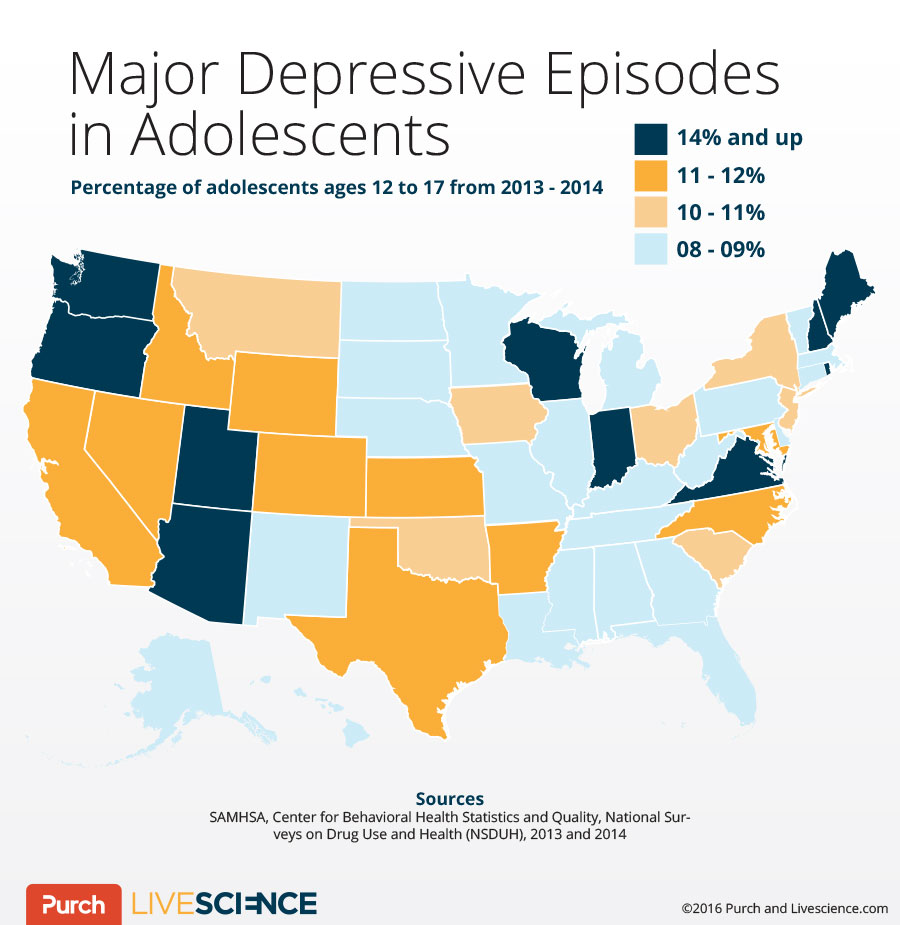

The report also broke down the rates of major depressive episodes in teens in each state. While the national average was 11 percent, rates ranged from a low of 8.7 percent in Washington, D.C., to a high of 14.6 percent in Oregon, the researchers found.

In addition, out of the 10 states with the highest rates, four were found in the West (Oregon, Arizona, Utah and Washington), according to the report. Of the 10 states with the lowest rates, four were found in the South (Tennessee, Georgia, Kentucky and Washington, D.C.).

Thirteen states had statistically significant increases in their rates; in the remaining states, the percentage of teens with a major depressive episode stayed the same between the two time points. [Infographic: Teens in 13 States Showed Increases in Major Depressive Episodes]

A number of factors may contribute to the differences in the rates of major depressive episodes across states.

For example, depression is more common in females than males, said Weissman, who is also the chief of the division of epidemiology at New York State Psychiatric Institute. So if you have more females in one state, that'll do it, she said. [7 Ways Depression Differs in Men and Women]

Health care also plays a role, Weissman said. In states with fewer health care services, such as states with more rural areas, it can be much harder for people to get health care, she said. This means that a higher percentage of people who had a major depressive episode may experience another episode, later on.

Religion and economic status should also be considered, Weissman said. Some religious groups may not look favorably upon mental health care, she said. And in states where the economy is struggling, rates of depression can be higher if people are unable to find jobs, she said. Though the report looked at teens, this issue can affect older teens who do not plan to go to college and who want to find work, Weissman added.

Episodes versus disorders

In the report, the researchers focused on instances called major depressive episodes.

These episodes are a core feature of what doctors call major depressive disorder, Talati said. But a single episode does not indicate how the disorder will progress for a particular person. For example, for some adolescents a depressive episode might represent a lone event, triggered perhaps by a specific life stress; for others, it may reflect the beginning of a longer course of illness with more frequent or impairing episodes, he said. [10 Facts Every Parent Should Know About Their Teen's Brain]

Indeed, it's not clear from the new report if these major depressive episodes in teens are first-time occurrences, or re-occurrences, Weissman added.

Still, the rates that reach over 10 percent are problematic, said Talati, who is also an investigator at the Sackler Institute for Developmental Psychobiology. Depression as a teenager can have an impact on the rest of a person's life, as well as that of their families, if it's not addressed, he said.

Depression in teens

Having a major depressive episode as a teen can increase a person's risk of having additional episodes later in life, Weissman said.

Moreover, part of being a teen is learning independence and autonomy, said Dr. Leslie Miller, an assistant professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore. If a teen is feeling bad due to depression, he or she may miss out on important milestones, she said.

Depression can also affect how teens perform in school and in social settings, Miller said. Failing a semester due to depression can change a person's trajectory in life, she added.

Weissman agreed. "Depression in adolescence can really affect one's life," she said. A teen may drop out of school, get involved with people that he or she shouldn't, or find it difficult to get a job, she said. "It's not a fruitful illness for flourishing," she added.

What to look for

It can be difficult for parents to distinguish between depression and run-of-the-mill teenage moodiness.

But there are signs that parents can look out for in their teens, including changes in sleep or appetite, loss of interest in activities the teens normally enjoy, social isolation, and increasing irritability, Miller told Live Science. [10 Scientific Tips for Raising Happy Kids]

But concerned parents don't have to find a specialist right away, Miller said. A pediatrician is a good person to ask first about possibly seeking more specialized mental health care; he or she can advise parents as to whether it would be helpful to see a mental health specialist, she said. Parents who are more familiar with depression, or have personal experience with it, may go straight to the specialist, she added.

Miller added that increasing awareness of mental illness, including depression, can help teens recognize symptoms as well. If a teen knows the symptoms of depression, he or she may be able to recognize feeling off, or not enjoying activities anymore, she said.

Overall, recognizing symptoms is a good thing.

There are a lot of ways to treat depression, Talati said. Aside from medications, there are a range of different psychotherapy options that have been shown to work, he said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus