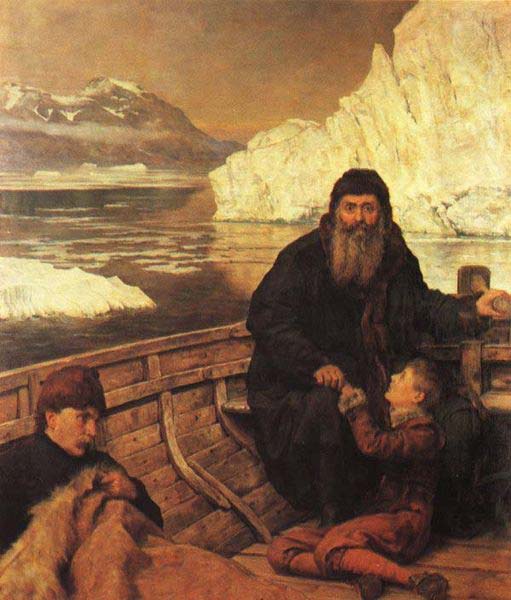

Mutiny or Murder: What Happened to Henry Hudson?

It has been 400 years since English explorer Henry Hudson mapped the northeast coast of North America, leaving a wake of rivers and towns named in his honor, yet what happened to the famed explorer remains a mystery.

Hudson was never heard from again after a mutiny by his crew during a later voyage through northern Canada. That he died in the area in 1611 is a certainty, and he may have even been killed in cold blood, according to new research.

The anger among Hudson's crew over his decision to continue exploring after the harsh winter could have easily fueled a murderous mutiny, suggests Peter Mancall, a professor of history at the University of Southern California. "The full story of Hudson's saga reveals one of the darker chapters of the European age of discovery," said Mancall, who explores the 1610 voyage in his new book "Fatal Journey: The Final Expedition of Henry Hudson" (Basic Books; 2009).

Hudson claims Manhattan

Before the fatal voyage that took his life, Henry Hudson found great success as a navigator the way many men did during the Age of Exploration – by accident.

Hired by the Dutch East India Company to find a new passage to spice-rich Asia by way of the Arctic Ocean, Hudson was ultimately forced by impassable ice to seek another route south. Sailing into what would eventually be named the Hudson River in 1609, he did not find the Northwest Passage he was looking for, but did manage to stake the first loose claim to the territory – including the island of Manhattan – on behalf of The Netherlands.

The value of the land he'd claimed for a foreign power wasn't lost on the rulers of his home country. Upon his return, England's royal council forbid Hudson from ever sailing under another flag, and he was sent back to the New World in 1610 aboard the English ship Discovery.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Hudson's objective was, once again, to find a northern passage to the Orient, but he would never return from that trip. The Discovery docked back in London in 1611 without having reached Asia, without the captain aboard and with just eight crew, all of whom were now subject to death by hanging for the murder.

Set adrift Some facts about the 1610-1611 voyage of the Discovery are certain.

Discovery plied the Canadian bay that also took Hudson's name in the summer of 1610, the captain believing that he'd possibly found the elusive northern passage to the Pacific. The ship was forced to ground itself for the winter, however, with Hudson ordering a return to the route the next spring, despite his crew's wish to return to England. When the ship took to the water again for its return trip in June, 1611, Hudson was not aboard.

On trial for Hudson's murder later that year, the remaining crew admitted to cutting the captain and a group of individuals still loyal to him loose on a small lifeboat, according to court documents.

None of the men was convicted of the murder or even punished for the mutiny, and historians generally believe their claims, too. But some physical evidence points to a more violent end for the captain, Mancall believes.

Mancall highlighted evidence that was found and documented after the ship docked in London: blood stains, most damningly, along with letters from another sailor mentioning the growing personal rift between captain and crew. A number of Hudson's possessions were also missing.

Brought down by determination

Since Hudson's body was never found, however, it will never be known for sure whether the captain was murdered or given a more subtle death sentence, set adrift in the harsh environment of northern Canada.

It was Hudson's steely nature to press on and meet his objective that led to his demise, whatever that may have been, historians agree.

"Hudson was one of the most intrepid and important explorers of his age," said Mancall. "He was not a man who easily gave up."

- History's Most Overlooked Mysteries

- 10 Events That Changed History

- How Weather Changed History

Heather Whipps is a freelance writer with an anthropology degree from McGill University in Montreal, Canada.