Scarred, Sunken Mastodon Hints at Earlier Human Arrival in Americas

Nearly 15,000 years ago, early humans gathered by a small pond in what is now Florida, near Tallahassee. Using stone knives, they butchered the body of a fallen mastodon, scoring the massive beast's tusks with deep cuts as they dug them out of the skull.

What happened immediately afterward is lost to time. But after many thousands of years, one of the tusks — scarred by cut marks — and knives that the hunters used were discovered, preserved alongside other artifacts under 13 feet (4 meters) of sediment that was also about 26 feet (8 m) underwater, in the Aucilla River.

A team of scientists recently investigated the artifacts in their underwater resting place, known as the Page-Ladson archaeological site. They concluded that the tools were 14,550 years old, thus providing rare physical evidence that places humans in the Americas earlier than previously suspected — by more than 1,000 years. [Watch video of divers uncovering the artifacts]

Earliest inhabitants

For decades, many archaeologists staunchly affirmed that humans settled in the Americas no earlier than 13,200 years ago. This group of early humans, known as the Clovis, was thought to have arrived from Asia, over the Bering land bridge.

In 1983, eight stone artifacts and butchered mastodon remains were discovered at the Page-Ladson site, and were investigated through 1997. The sediments surrounding the finds were dated to 14,400 years ago, but at the time, it was unthinkable to suggest that humans arrived in North America more than 1,000 years prior to the Clovis, the authors of the new study explained. Experts back then argued that even if the sediments were over 14,000 years old, it was possible that the artifacts themselves were not, and that they had been carried to that part of the site by river currents.

However, as years passed and evidence of these pre-Clovis people accumulated from other sites, the idea that humans occupied the Americas between 14,000 and 15,000 years ago began to take hold. When scientists returned to the Page-Ladson site between 2012 and 2014, they used radiocarbon dating on the artifacts, confirming that they were 14,550 years old and finally proving that the initial estimates of the site's advanced age were correct.

To establish a human presence at a specific location during a specific time archaeologists consider several important factors, study co-author Michael Waters of Texas A&M University explained in a teleconference

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

First, he said, you need evidence of human activity — stone tools, for example. Next, you link the tools to the location, to make sure they didn't get there by accident. The Page-Ladson finds were buried deep under sediment, so it was likely that they were part of that original landscape. Finally, the artifacts must be dated using a reliable technique.

"At Page-Ladson, we meet all three criteria," Waters said. "Artifacts are associated with the mastodon remains, including a tusk with tool marks. They were sealed in undisturbed geological deposits. Seventy-one new radiocarbon dates show the artifacts date to 14,500 years ago. The Page-Ladson site provides unequivocal evidence of human occupation that predates Clovis by over 1,500 years." [In Photos: Mastodon Tusk Marked by Human-Made Tools]

"As dark as the inside of a cow"

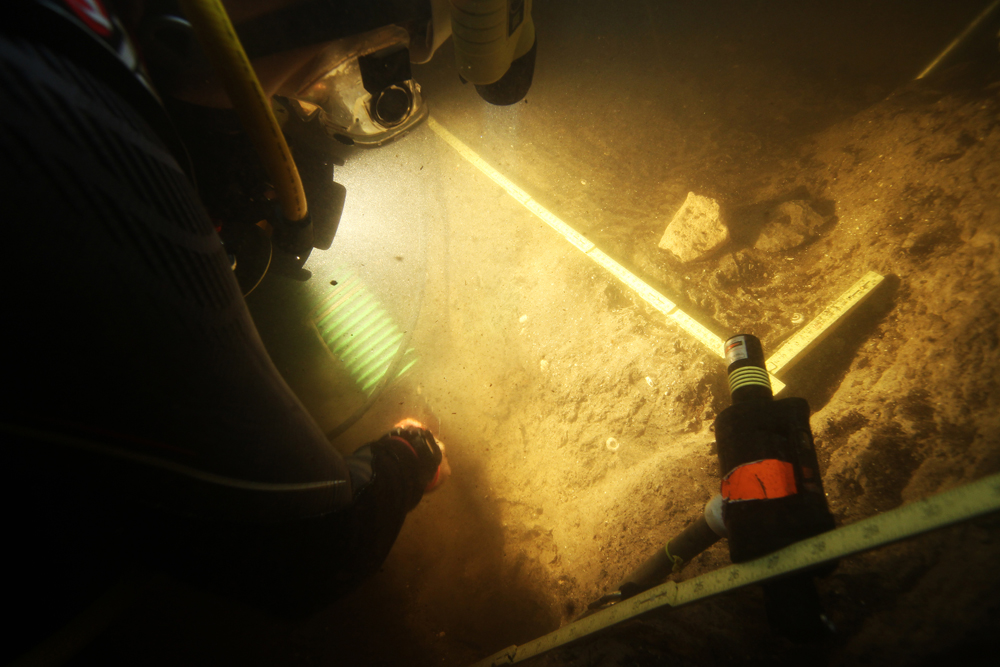

Exploring the Page-Ladson site was no easy task. Study co-author Jessi Halligan of Florida State University was also the lead diver and excavation manager, and she described working in unusually murky waters. It was "as dark as the inside of a cow," she said. Rainwater seeping through the ground stained the river so dark that the divers could only work while using dive lights, and even then, the visibility was limited to the area directly in front of them.

Which can be disorienting at first, "but it's really not as big a limitation as it sounds," Halligan said. "When you do your job, you're usually just looking at your excavation square anyway."

And there were some distinct advantages to digging underwater. Halligan compared the environment to working in zero gravity — rather than crouching in one position for hours on end, the archaeologists could work sideways or even upside down. And while aboveground diggers must dispose of displaced dirt, the divers had specialized pumps at the surface powering underwater vacuums, creating a vortex that sucked water and sediment away as the divers were working.

But if you were to empty out all of the water, it would look very much like any terrestrial dig site, with taut string boundaries dividing it into areas of interest, Halligan added. [Mammoth vs. Mastodon: What's the Difference?]

Cutting it out

Deciphering the marks on the tusks proved to be yet another challenge — one that the scientists anticipated might yield important clues about the ancient people who made the cuts.

"Marks made by the tool can be as diagnostic of human activity as the tool itself," said study co-author Daniel Fisher of the University of Michigan. "They say a great deal. Not just about who produced the pattern, but about what behavior was responsible for the pattern."

After reconstructing the tusk, Fisher linked the marks to cutting motions that would have separated the tusk from particularly tough ligaments in the tusk socket. He suggested that early humans might have wanted to remove the tusk for its ivory, but the nutritious and plentiful tissue in the tusk cavity — about 15 lbs. (6.8 kilograms) per tusk — also could have been their goal.

While the researchers' work provides a glimpse into the distant world that these ancient hunter-gatherers inhabited, it raises many more questions about their lifestyle and their impact on the terrestrial megafauna like the mastodon, with which they overlapped for 2,000 years before the mastodon was driven to extinction.

"The record of human habitation in the Americas between 14,000 and 15,000 years ago is sparse — but it is real," Waters said in the teleconference.

"Clearly, humans were exploring and settling at this time — the rarity of these early sites is likely due to low population densities," he said. "And in some cases such as Page-Ladson, this evidence is submerged. This will make finding these sites difficult but very important — tools left behind 14,500 years ago will have a profound impact on our understanding of the earliest pioneers of the Americas."

The findings were published online today (May 13) in the journal Science Advances.

Follow Mindy Weisberger on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.