First Migrants to Imperial Rome ID'd by Their Teeth

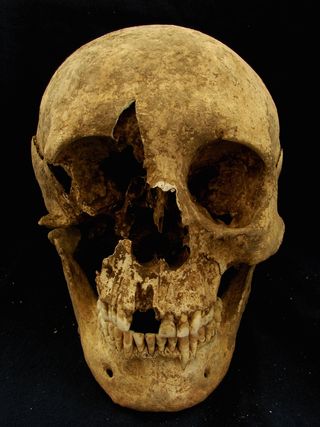

Three adult men and a young adolescent of unknown gender buried in cemeteries outside Rome were likely migrants to the city, their teeth reveal.

The four immigrants all lived during the first to third centuries A.D. They are the first individuals ever to be identified as migrants to the city during the Roman Imperial era, which began around the turn of the millennium and ended in the fourth century.

This was a time when Rome was a thriving, complex metropolis, said study researcher Kristina Killgrove, a biological anthropologist at the University of West Florida.

"Up to a million people were living there," Killgrove told Live Science. "This population ebbed and flowed. You had people who were migrating in, and you had people who were dying and [people who were] migrating out." [See Photos of the Ancient Roman Burials]

Hidden history

Previous researchers have estimated that 40 percent of the people who lived in Rome during this period were slaves (some born locally and some imported), and about 5 percent were voluntary migrants to the city. But there was no census in Rome and no records of the comings and goings of individuals, Killgrove said.

She searched for evidence of these early travelers in two cemeteries right outside Rome's walls — Casal Bertone to the east, and Castellaccio Europarco to the south. To uncover people's origins, Killgrove and colleague Janet Montgomery of Durham University in the United Kingdom analyzed the isotopes in their molars. They focused on the first molar, which starts forming at birth and finishes forming at age 4. The enamel of this molar holds a record of what people ate and drank in their first years. [Photos: Gladiators of the Roman Empire]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Teeth are kind of like little time capsules in your mouth," Killgrove said.

Isotopes are versions of the same element with different numbers of neutrons in their nuclei. The researchers analyzed strontium isotopes in molars from 105 skeletons from the two cemeteries, and further analyzed oxygen and carbon isotopes in a subset of 55 of those individuals. Strontium enters food and water by the weathering of rocks and indicates the geology of an area where a person spent his or her first years. Oxygen reflects the source of a person's drinking water, including meteorological factors like humidity and rainfall. Carbon can provide information about a person's diet, particularly whether plants rich in the isotope C4 (maize and millet, for example) or C3 (rice and wheat, among others) were eaten.

Trading places

A combination of these isotopes revealed that two adult men who were between 35 and 50 when they died, one adult man older than 50, and a teenager between the ages of 11 and 15 almost certainly came to Rome from somewhere else. A couple of the men had high levels of certain strontium isotopes, indicative of starting life in a place where the rocks are old. Much of Italy is made of young, volcanic rocks, Killgrove said. The closest old rocks are in the Alps, or on some of the islands of the Tyrrhenian Sea. The oxygen isotope analysis also hinted that these two men could have come from an Alpine climate, though it's impossible to be sure, Killgrove and Montgomery reported.

The adolescent had low strontium isotope levels, suggestive of a home environment of young limestones or basalt. High oxygen isotopes ratios pointed to a hot climate. Those clues suggest a possible North African origin for this young person.

Four other individuals (two 7- to 12-year-olds, a male between the ages of 11 and 15 and a female between the ages of 16 and 20) also had isotope signatures that suggested they may not have been native Romans, but the data was a bit ambiguous, Killgrove said. Figuring out if people migrated to Rome is particularly difficult because people in the city ate imported food and drank water drawn from large areas through aqueducts, meaning their isotope ratios have a broader range than people living in a more self-contained city.

It's impossible to tell why the migrants found in the Roman cemeteries moved, Killgrove said. They may have been slaves, or they may have come to Rome for voluntary reasons. The burials appear to be those of lower-class people, Killgrove said, but that doesn't mean they weren't free. Notably, the immigrants' diets do seem to have changed when they moved to Rome. As children, they ate diets higher in C4 foods, probably millet, Killgrove said.

"When they came to Rome, that becomes more in line with the Roman diet, which is more wheat-based than millet-based," she said. (Killgrove has previously found class differences in the amount of millet and wheat eaten by Romans.)

Killgrove is now working at another cemetery site outside Rome and plans more isotope analysis, along with DNA studies. An understanding of migration can deepen an understanding of Rome's development, as well as Imperial Roman slavery, acculturation to Roman culture and even disease transmission.

"It all goes back to migration," Killgrove said.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular