Tomb Tells Tale of Family Executed by China's 1st Female Emperor

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A 1,300-year-old tomb, discovered in Xi'an city, China, holds the bones of a man who helped the nation's only female emperor rise to power. The epitaphs in the tomb describe how she then executed him and his entire family.

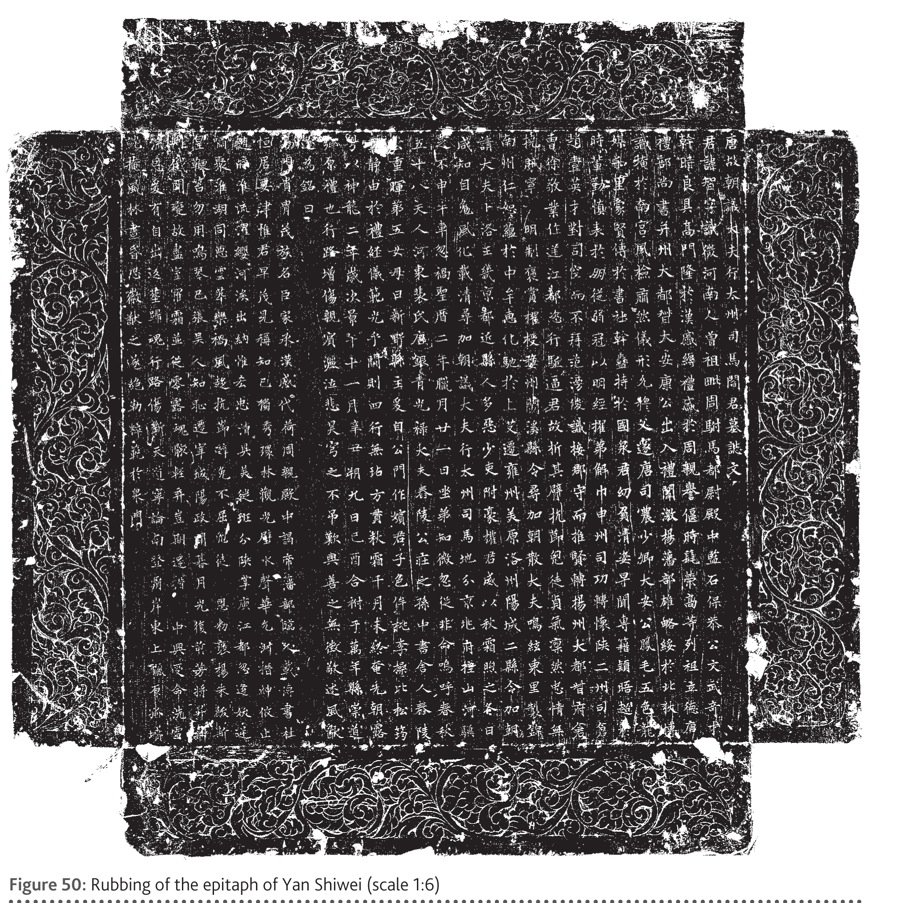

Located within a cave, the tomb contains the remains of Yan Shiwei and his wife, Lady Pei. While little is left of the individual's skeletons, archaeologists found colorful ceramic figurines, a mirror with a gold plaque and, most importantly, epitaphs inscribed on bluestones.

The tomb and its epitaphs were described recently in the journal Chinese Cultural Relics by researchers from the Xi'an Municipal Institute of Archaeology and Conservation of Cultural Heritage. [See Photos of the Chinese Tomb Site and Treasures]

A woman comes to power

Wu Zetian started out as a concubine of Emperor Gaozong (649-683), eventually becoming his empress and gaining a high degree of influence over him.

After the emperor's death, Wu Zetian declared that she would rule China as Empress Dowager with her son, Emperor Ruizong. The epitaphs say that shortly after her declaration, a duke named Xu Jingye led a rebellion in Jiangdu (modern-day Yangzhou).

At this time, according to the translated epitaphs, Yan Shiwei was serving as a military official in Jiangdu; the duke, Jingye, tried to persuade Shiwei to join the rebels, but Shiwei refused and fought against the duke.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"The lord [Yan Shiwei] intentionally broke his own arm to resist the coercion from the rebel, showing that his loyalty to the imperial court had not been shaken," the epitaphs read in translation. It's unknown why Shiwei had to intentionally break his own arm. It could have been during hand-to-hand fighting while trying to get out of a hold. It's also possible that the phrase is metaphorical. [In Photos: Gladiators of the Roman Empire]

In the ensuing conflict the duke's forces were defeated. Wu Zetian claimed power as Empress Dowager, and Yan Shiwei was promoted.

"After the rebels were defeated, the lord received his reward. He was promoted to magistrate of Lanxi County of Wuzhou Prefecture and given the title of grand master for closing court," the epitaphs say.

In 690, Wu Zetian declared herself emperor in her own right and founded her own dynasty, which she called the "Zhou."

As Wu Zetian's power increased, Yan Shiwei became one of her favorite officials, taking on those who challenged her authority. The epitaphs say that at one point Yan Shiwei was charged with confronting "powerful families" near the capital city of Luoyang. The texts say that civil disorder was occurring.

"There were more spoiled young bullies in the counties near the capital, and the local officials feared those powerful families," the epitaphs say. Yan Shiwei resolved the situation, although the epitaphs are vague on how he did it, saying that "the lord was strict as the autumn frost, as well as warming as the winter sun, and got the people to learn self-control, and civil order was established."

Betrayal and downfall

By 699, Yan Shiwei had become a senior official who "was stationed in the capital area and controlled mountains and rivers," the texts alluding to his great power.

The epitaphs say that Yan Shiwei had little time to enjoy his power before he was executed. "Before he started galloping, a tragedy descended upon him," the epitaphs say, explaining that his younger brother, Zhiwei, turned against the female emperor. The epitaphs don't specify precisely what Zhiwei did, but the consequences for Yan Shiwei and his family were severe.

"Due to guilt by association for the crime of his brother Zhiwei, he [Yan Shiwei] was executed under collective punishment," the epitaphs say, adding that "the entire family suffered collective punishment, and all were executed."

Yan Shiwei's wife, Lady Pei, had died a few years earlier, in 691, so she was not killed in the mass execution.

The epitaphs also suggest that murder was not enough of a punishment for Yan Shiwei's supposed betrayal. "The corpse and soul were carelessly buried, it being thought it would never be possible to move them for proper burial."

However, the female emperor was thrown out of power in 705, and died shortly afterward, bringing an end to her short-lived "Zhou" dynasty. The dynasty that had preceded her, called the "Tang," was restored to power.

"The resurrection of the Tang Dynasty brought exoneration [for Yan Shiwei]. Therefore, his remains were exhumed to be buried at his birthplace," the epitaphs say. The "tomb [that the archaeologists found] was built to house his remains," the writings say.

The tomb was excavated in 2002. The finds were first reported in Chinese in 2014 in the journal Wenwu. Recently, the Wenwu article was translated into English and published in the journal Chinese Cultural Relics.

Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus