Worst Megadroughts in 1,000 Years Threaten US

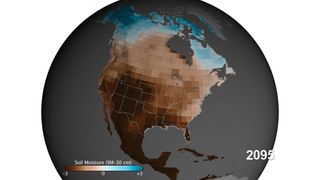

Before this century ends, the Southwest and Central Plains states are likely to shrivel under a decades-long megadrought worse than those that ended the Ancestral Pueblo civilization in the last millennia, a new study finds.

Based on tree-ring records, scientists know that severe droughts coincided with the collapse of the Ancestral Pueblo culture. Great droughts struck in the 1100s and 1200s, at the same time as the abandonment of the stone villages at Mesa Verde, Chaco Canyon and elsewhere on the Colorado Plateau.

Now, researchers have used the same tree-ring records to divine the future of drought in the United States. After analyzing climate models that include historical records and looking at drought trends revealed in tree rings over the last 1,000 years, scientists predict a strong possibility of megadroughts before 2100 in the Southwest and Central Plains. There is an 85 percent chance of a drought lasting 35 years or more between 2050 and 2100, said study co-author Toby Ault, a climate scientist at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. [The Worst Droughts in US History]

"The future of drought in western North America is likely to be worse than anybody has experienced in the history of the United States," said lead study author Benjamin Cook, a climate scientist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies in New York City. "These are droughts that are so far beyond our contemporary experience that they are almost impossible to even think about," Cook said.

The findings were published today (Feb. 12) in the journal Science Advances.

Too hot, hot, hot

A megadrought is a prolonged dry spell that lasts for a decade or more. The worst megadroughts to strike the West preceded European settlement, such as the great droughts in the 1100s and the 1200s. Tree ringsare time capsules for drought because they grow wider during wet years and narrower during dry years.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Climate models have already indicated that megadroughts threaten the Southwest this century. The models predict the Southwest will become drier in the future as climate change shifts global weather patterns. In the Central Plains, the northern areas may become wetter and the southern areas may become drier.

However, the new study finds that rising temperatures are a bigger threat than a lack of rain and snow. Compared with the great dry spells that hit 1,000 years ago, this century will see higher temperatures in the Southwest because of greenhouse gas emissions, the researchers said. The warmth will increase drought severity by speeding the loss of moisture from the soil to the air, a process called evapotranspiration, Cook said. Global temperatures in 2014 were the hottest on record since the 1850s, according to four independent groups.

The rising temperatures will favor longer, more severe droughts. This will happen even in those areas of the West and Central Plains that may actually see more, not less, winter rain and snow in the future, the study researchers report.

"This is an amazing result," said David Stahle, a paleoclimatologist at the University of Arkansas. "The precipitation is not so dire. It is the escalation in temperature that is driving the model simulations toward dramatic aridity," added Stahle, who was not involved in the study.

However, both Stahle and Cook note that the results are more conclusive for the Southwest than for the Central Plains. One reason for the uncertainty is that tree-ring records in the West are exquisitely detailed compared with the history available for the Plains states.

The drying problem

In California, record-high temperatures last year worsened the state's exceptional drought, according to a separate study published in December 2014. California's current dry spell is part of an ongoing 15-year drought plaguing much of the Southwest.

The new findings reveal future droughts will arise from different causes than previous droughts, the researchers said. The megadroughts during the 1100s and the 1200s were triggered by natural ocean-atmosphere cycles, such as cooler temperatures in the Pacific Ocean that shifted weather patterns toward drier conditions in the Southwest. But the drying effect from warming will eventually overwhelm those cycles in these regions, Cook said. [The 10 Most Surprising Results of Global Warming]

"Those [historical] droughts eventually ended, and we moved on to wetter periods," Cook said. "This future drying represents a fundamental change and shift toward drier average conditions in western North America. There's little evidence we're going to bounce back to what we had, because of greenhouse gases."

A huge mistake on water

The coming megadroughts will have profound effects on water resources and agricultural productivity. Water rights in the West were carved up during the 1920s, one of the wettest periods in the past 500 years. "It's kind of bad luck that we based our water accounting on those really wet decades," Cook said. And the West's population explosion between 1980 through 2000 also coincided with wetter than normal decades. Now, with nearly every drop of surface water legally claimed, cities and famers make up any deficit by tapping nonrenewable underground aquifers, which are already straining to meet current demands.

"The future of the United States west of the Mississippi is hot and it is dry," said Kevin Anchukaitis, a paleoclimatologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, who was not involved in the study.

Follow Becky Oskin @beckyoskin. Follow LiveScience @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Originally published on Live Science.

Most Popular