New Super-Heavy Element 117 Confirmed by Scientists

Atoms of a new super-heavy element — the as-yet-unnamed element 117 — have reportedly been created by scientists in Germany, moving it closer to being officially recognized as part of the standard periodic table.

Researchers at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research, an accelerator laboratory located in Darmstadt, Germany, say they have created and observed several atoms of element 117, which is temporarily named ununseptium.

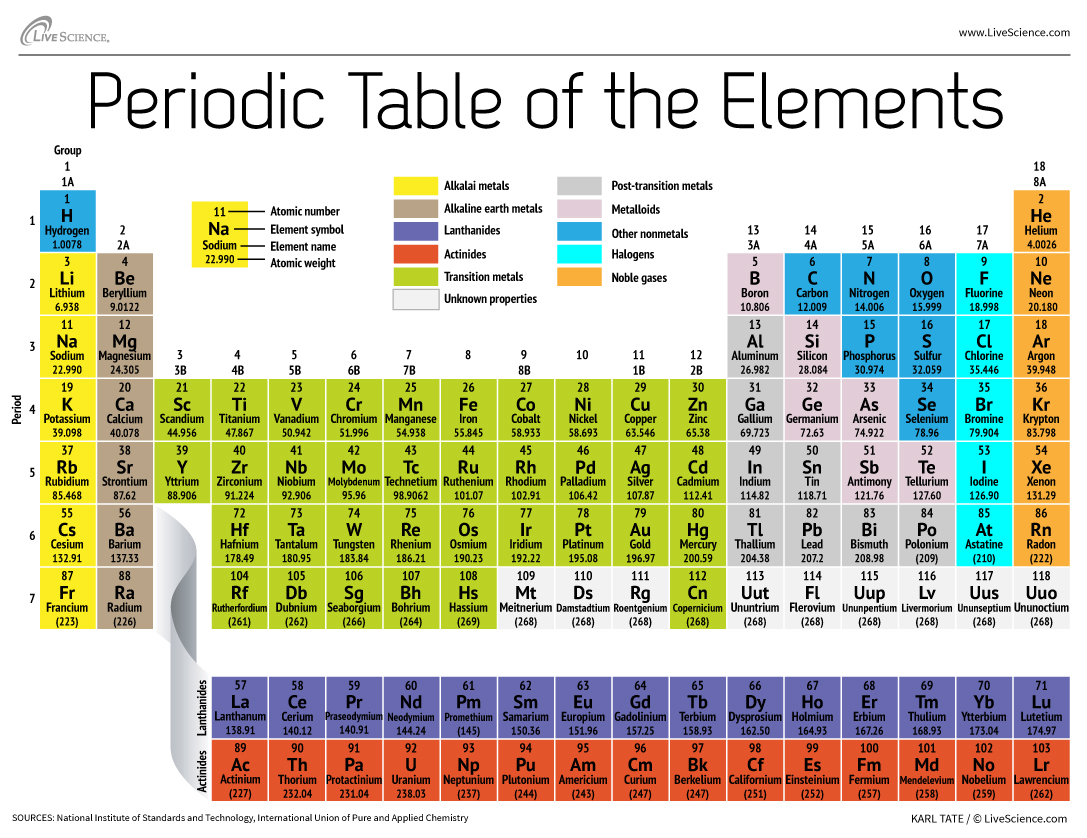

Element 117 — so-called because it is an atom with 117 protons in its nucleus — was previously one of the missing items on the periodic table of elements. These super-heavy elements, which include all the elements beyond atomic number 104, are not found naturally on Earth, and thus have to be created synthetically within a laboratory. [Elementary, My Dear: 8 Elements You Never Heard Of]

Uranium, which has 92 protons, is the heaviest element commonly found in nature, but scientists can artificially create heavier elements by adding protons into an atomic nucleus through nuclear fusion reactions.

Over the years, researchers have created heavier and heavier elements in hopes of discovering just how large atoms can be, said Christoph Düllmann, a professor at the Institute for Nuclear Chemistry at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz. Is there a limit, for instance, to the number of protons that can be packed into an atomic nucleus?

"There are predictions that super-heavy elements should exist which are very long-lived," Düllmann told Live Science. "It is interesting to find out if half-lives become long again for very heavy elements, especially if very neutron-rich species are made."

Typically, the more protons and neutrons are added into an atomic nucleus, the more unstable an atom becomes. Most super-heavy elements last just microseconds or nanoseconds before decaying. Yet, scientists have predicted that an "island of stability" exists where super-heavy elements become stable again. If such an "island" exists, the elements in this theoretical region of the periodic table could be extremely long-lived — capable of existing for longer than nanoseconds — which scientists could then develop for untold practical uses, the researchers said. (A half-life refers to the time it takes for half of a substance to decay.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Düllmann and his colleagues say their findings, published today (May 1) in the journal Physical Review Letters, are a step in the right direction.

"The successful experiments on element 117 are an important step on the path to the production and detection of elements situated on the 'island of stability' of super-heavy elements," Horst Stöcker, scientific director at the GSI Helmholtz Center for Heavy Ion Research, said in a statement.

Element 117 was first reported in 2010 by a team of American and Russian scientists working together at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia. Since then, researchers have performed subsequent tests to confirm the existence of the elusive new element.

A committee from the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), the worldwide federation charged with standardizing nomenclature in chemistry, will review the findings to decide whether to formally accept element 117 and grant it an official name.

Live Science news editor Megan Gannon contributed reporting to this article.

Follow Denise Chow on Twitter @denisechow. Follow Live Science @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on Live Science.

Denise Chow was the assistant managing editor at Live Science before moving to NBC News as a science reporter, where she focuses on general science and climate change. Before joining the Live Science team in 2013, she spent two years as a staff writer for Space.com, writing about rocket launches and covering NASA's final three space shuttle missions. A Canadian transplant, Denise has a bachelor's degree from the University of Toronto, and a master's degree in journalism from New York University.