Dinosaur Bone Damaged in WWII Revealed with 3D Printing

The identity of a mislabeled fossil damaged in a World War II era bombing has finally been revealed as part of an enormous long-necked plant-eating dinosaur.

The fossil, tucked inside the plaster jacket paleontologist wrapped around it more than 100 years ago, belongs to the Museum of National History in Berlin. During World War II, a bomb fell on the museum's east wing, collapsing the basement where dinosaur fossils were stored.

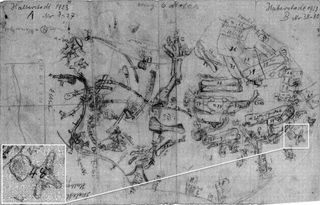

Many fossils were reduced to dust in the bombing, and the ones that survived were scattered and mixed up. Making matters worse, bones from two separate expeditions had been housed in the same area. One expedition, in Tanzania, ran from 1909 to 1913 and brought back 235 tons of fossils, labeled with letters based on their locations. The other fossils came from a 1909 discovery in Halberstadt, Germany. Those bones also used a letter-based label system — but the letters referred not to locations, but to individual animals. [See Photos of Amazing Dinosaur Fossils]

In other words, it was a mess.

"It is still difficult for them to sort out some of the objects, because some of the labeling was destroyed," said study researcher Ahi Sema Issever, a radiologist at the Charité hospital in Berlin.

Mystery bone

Museum paleontologists approached Issever for her help identifying one of the mystery fossils. The fossil was labeled as coming from the Tanzania dig, but members of the museum staff weren't so sure. Using the computed tomography (CT) scans that are usually used to diagnose sick patients, researchers can peer inside the plaster and rock that surrounds the fossils to identify the bones inside.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

CT scanning is a boon for paleontologists, because preparing fossils is slow, painstaking work, Issever told LiveScience. Fossil prep can also be risky, as fragile bones can easily crumble or break under a preparator's chisel.

The scans revealed a dinosaur vertebra that was 8 inches (21 centimeters) long and 6 inches (17 cm) wide. It belonged to Plateosaurus, an herbivore that could grow to be 33 feet (10 meters) long.

By comparing the scans to sketches of the long-ago digs, the researchers determined that the vertebra came from the Halberstadt dig in Germany. In the chaos of the museum basement after the war, it had been mislabeled as Tanzanian.

Printing a dinosaur

The scans showed a fractured bone. Some of the cracks were no doubt from fossilization, Issever said. But one crunched-up corner was likely the result of the bombing. To recreate the bone as it was before the bombing, the researchers took data from the CT scan and built a blueprint to 3D print the fossil. Three-dimensional printing is an emerging method in paleontology, with researchers using the tech to create perfect scale models of bones.

To do so, the researchers used a technique called laser sintering. In this technique, a laser is programmed to heat a plastic powder, melting it layer by layer into the desired shape. When the process was done, the unheated powder was brushed away, revealing a dino bone copy, accurate down to a micrometer (one-thousandth of a millimeter). The researchers were even able to print the bone chip from the bombing damage, which fit into the rest of the vertebra like a puzzle piece.

"I'm just happy that it really worked out," said Issever. She and her colleagues will likely work with the museum in the future to scan other unknown fossils, she said.

The researchers reported their findings today (Nov. 20) in the journal Radiology.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Most Popular