'Meat Mummies' Kept Egyptian Royalty Well-Fed After Death

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Care for some ribs? The royal mummies of ancient Egypt apparently did, as a new study finds that "meat mummies" left in Egyptian tombs as sustenance for the afterlife were treated with elaborate balms to preserve them.

Mummified cuts of meat are common finds in ancient Egyptian burials, with the oldest dating back to at least 3300 B.C. The tradition extended into the latest periods of mummification in the fourth century A.D. The famous pharaoh King Tutankhamun went to his final resting place accompanied by 48 cases of beef and poultry.

But meat mummies have been mostly unstudied until now. University of Bristol biogeochemist Richard Evershed and his colleagues were curious about how these cuts were prepared. They also wondered if the mummification methods for meat differed from how Egyptians mummified people or pets.

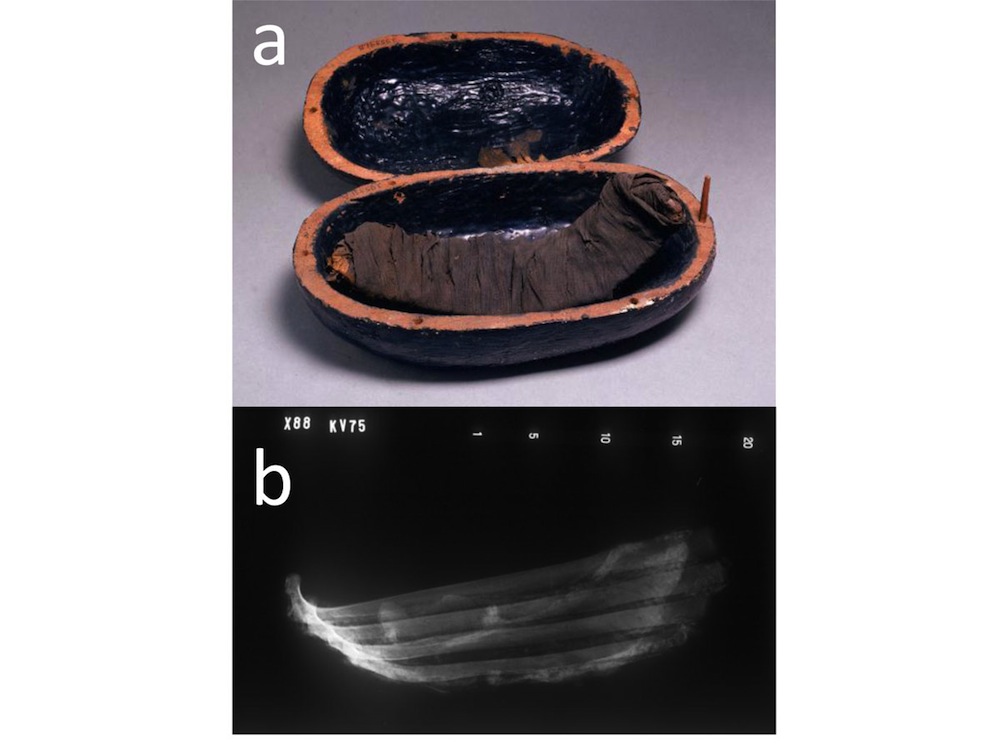

The team analyzed four samples from meat mummies archived at the Cairo and British museums. The oldest was a rack of cattle ribs from the tomb of Tjuiu, an Egyptian noblewoman, and her courtier Yuya. The beef dates back to between 1386 B.C. and 1349 B.C. [Gallery: Scanning Mummies for Heart Disease]

The second sample dated to between 1064 B.C. and 948 B.C. and consisted of meat from a calf found in the tomb of Isetemkheb D, a sister and wife to a high priest in Thebes. The final two samples were from the tomb of a Theban priestess, Henutmehyt, who died around 1290 B.C. One of the meat mummies found in Henutmehyt's tomb was duck, and the other was probably goat.

The researchers conducted a chemical analysis of the bandages or the meat itself in all four samples. They found that animal fat coated the bandages of the calf and goat mummies; in the case of the calf, the fat was on bandages not in contact with the meat, suggesting it had been smeared on as a preservative rather than seeping through as grease.

The most intriguing chemical profile appeared on the beef mummy, however. The bandaging around the mummy contained remnants of an elaborate balm made of fat or oil and resin from a Pistacia tree, a shrubby desert plant. This resin was a luxury item in ancient Egypt, Evershed and his colleagues report today (Nov. 18) in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. It was used as incense and varnish on high-quality coffins, but it was not used as a human mummification resin for at least 600 years after the deaths of Tjuiu and Yuya.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Nevertheless, it makes sense to see a sophisticated embalming substance on the beef cut, the researchers wrote. Yuya and Tjuiu were an Egyptian power couple and the parents of the wife of pharaoh Amenhotep III. As the queen's parents, they would have merited a no-expenses-spared burial.

Follow Stephanie Pappas on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus