Tectonic Plates’ Patterns Revealed

The biggest jigsaw puzzle in the solar system has a split personality: The number and sizes of Earth's tectonic plates can flip, according to a new study.

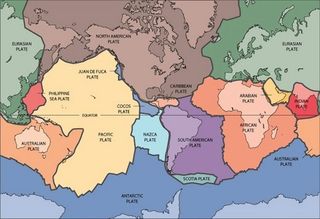

Today, the pieces of Earth's broken shell are unequal in size. Of about 50 plates, a mere seven account for 94 percent of the surface. The biggest, the Africa and the Pacific plates, are antipodal, meaning they sit on opposite sides of the Earth.

But about 100 million years ago, the tectonic plates tiled the planet as evenly as a real-life jigsaw puzzle.

"The distribution of the large plates has not always been the same," said lead study author Gabriele Morra, a geodynamicist at the University of Louisiana in Lafayette. "The large plates have really oscillated between different patterns. This has strong implications for what is driving Earth's mantle convection," Morra told LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Morra also found that the number of small plates was about the same for the past 60 million years. "This means that if you want to understand Earth's evolution, the interesting part is the large plates," Morra said. "The large plates will tell us what's really going on."

Earth's alternating plate engine

Plate tectonics theory holds that Earth's crust is divided into plates, which move across the underlying mantle at a rate of inches (centimeters) a year. The model helps explain Earth's changing surface now and in the past, from the tallest mountains to the deepest earthquakes. But geoscientists actively debate whether the slow shuffle of tectonic plates comes from either pulling by sinking slabs of crust or pushing by convection currents in the hot, rocky mantle — or both. [Infographic: Tallest Mountain to Deepest Ocean Trench]

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Morra and his colleagues put together a detailed reconstruction of Earth's plates for the past 200 million years. To explain the switch in plate sizes, they suggest Earth's plate tectonic engine may alternate between the plate- and mantle-driven models.

When large plates dominate, then "top-down" tectonics prevails, with big, sinking plates running the show, the researchers said. This was the case about 200 million years ago, when the supercontinent Pangaea covered the planet. It's also today's tectonic setting, with the giant Pacific plate diving down into the mantle. But when the puzzle pieces are evenly spaced, then "bottom-driven" mantle forces dominate, the researchers said. Computer models of bottom-driven convection produce similar results, Morra said. "When you do these experiments, you tend to have this constant plate size," he said.

"I think what this work helps us understand is that plate tectonics is not simply driven by one process," Morra said. "Clearly this poses more questions than answers, but it reinforces the view that the Earth goes through radical global changes," he said.

Open question

Geophysicist Scott King, who was not involved in the study, said that whether the pattern of plates is controlled by the mantle and or by plates themselves remains an open question for the field.

"It is a pretty important question and I'm not sure that we have explored the depths of that question the way we need to," said King, a geophysicist at Virginia Tech. "This study strikes me as a very interesting and creative attempt to actually look at what we can say about the Earth through time."

The findings were published July 1 in the journal Earth and Planetary Letters.

Email Becky Oskin or follow her @beckyoskin. Follow us @OAPlanet, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience's OurAmazingPlanet.

Most Popular