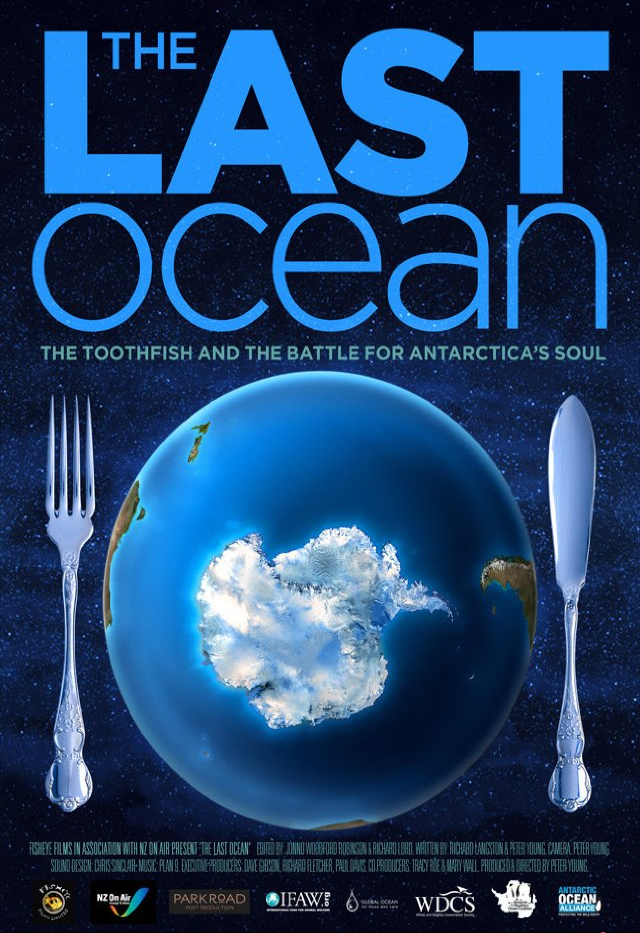

The Last Wild Ocean

The Ross Sea, a bay in the Antarctic, is so clear of particular matter that you can see 500 feet in all directions. Weddell seals float by divers with little fear. It has little pollution, invasive species and so far, has not been overfished. It is so cold that if you drop a steel spanner on concrete, it’d shatter. A quarter of the world’s emperor penguins and 40 percent of Adélie penguins live there and rely on this ocean.

That’s the sense of wonderment conveyed by The Last Ocean, a documentary by filmmaker Peter Young that is playing at film festivals. Using stunning visuals from Antarctica, the documentary is at its most convincing when it lays out its central conflict.

In the Ross Sea exists the Antarctic toothfish (Dissostichus mawsoni), best known to American consumers as Chilean sea bass or White Gold. The fish can grow two meters, weigh 140 kilograms, and it cooks well, chefs say. There’s little you can do to make bad Chilean sea bass.

Whole Foods Seafood Ban: Meet the Fish: Photos

Beginning in the 1997, fishing vessels led by New Zealand went into the icy Ross Sea in search of the toothfish. The nation now catches 55 percent of the fish and Americans consume 40 percent of whatever they catch. Illegal fishing is thriving as well. The net result is that the catch per unit area, which measures the abundance of a species, has been declining since 2001.

As Pogo would say, we’ve met the enemy and it is us. The fish occupies an important ecological role in the Antarctic, and its loss will affect food webs that include killer whales and Weddell seals.

The toothfish dilemma is reminiscent of other debates about our role in the planet. There are very few truly wild places left in our world. Environmentalism in its original form would seek to protect these places from humans by setting them apart. That’s what Young wants for the Ross Sea.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

But a newer type of environmentalism has taken hold in Washington, DC and other power centers of the world where sustainability has become the goal, as activist Paul Kingsnorth wrote last year in the Orion Magazine. He described sustainability as the need to maintain our lifestyle, in all its comfort, without entirely destroying the natural world. It is a delicate balance that means getting to eat Chilean sea bass while knowing that the fish will not entirely die out.

Sustainability, it appears, is what the nations regulating fishing in the Ross Sea are aiming for. The Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources or CCAMLR regulates fishing in the Antarctic and it has allowed industry to harvest half the toothfish population by 2035. The Marine Stewardship Council has certified some toothfish fisheries as sustainable. Young suggests in the documentary that this is problematic given the lack of knowledge about the species, and he casts doubt on the council’s independence.

Seeking Protection for Antarctic Waters: Analysis

This is a drawback of the documentary. It portrays New Zealand, the Marine Stewardship Council, and the fishing companies as somehow uniquely villainous. It treads lightly on the moral culpability of the rest of us who consume the fish or who prefer to remain ignorant of this fight over the last ocean.

The CCAMLR will meet next month to consider to debate the future of the sea. It is unlikely they will enforce a complete ban on fishing because 25 nations have to agree on it. The United States and New Zealand have proposed a marine protected area that covers large parts of the sea while still allowing for some fishing. For now, it’s time to wait and perhaps debate the merits of sustainability.

This story was originally published on Discovery News.