Should you really pee on a jellyfish sting?

Is it fact or folklore that peeing on a jellyfish sting is a good way to treat it?

It's an iconic scene: A beachgoer is stung by a jellyfish and is writhing in pain. Desperate, the victim allows someone to do the unthinkable — pee on them.

Urinating on a jellyfish sting to relieve the pain is infamous thanks to TV shows like "Friends." But does pee really help relieve the ache of a jellyfish sting? It turns out, urine is likely to make the sting worse, not better.

Experts agree that peeing on a jellyfish sting doesn't offer any real benefit. The myth likely started because urine contains ammonia and urea, giving it a slightly basic pH, Jessica Colla, director of education at the Maui Ocean Center in Hawaii, told Live Science in an email.

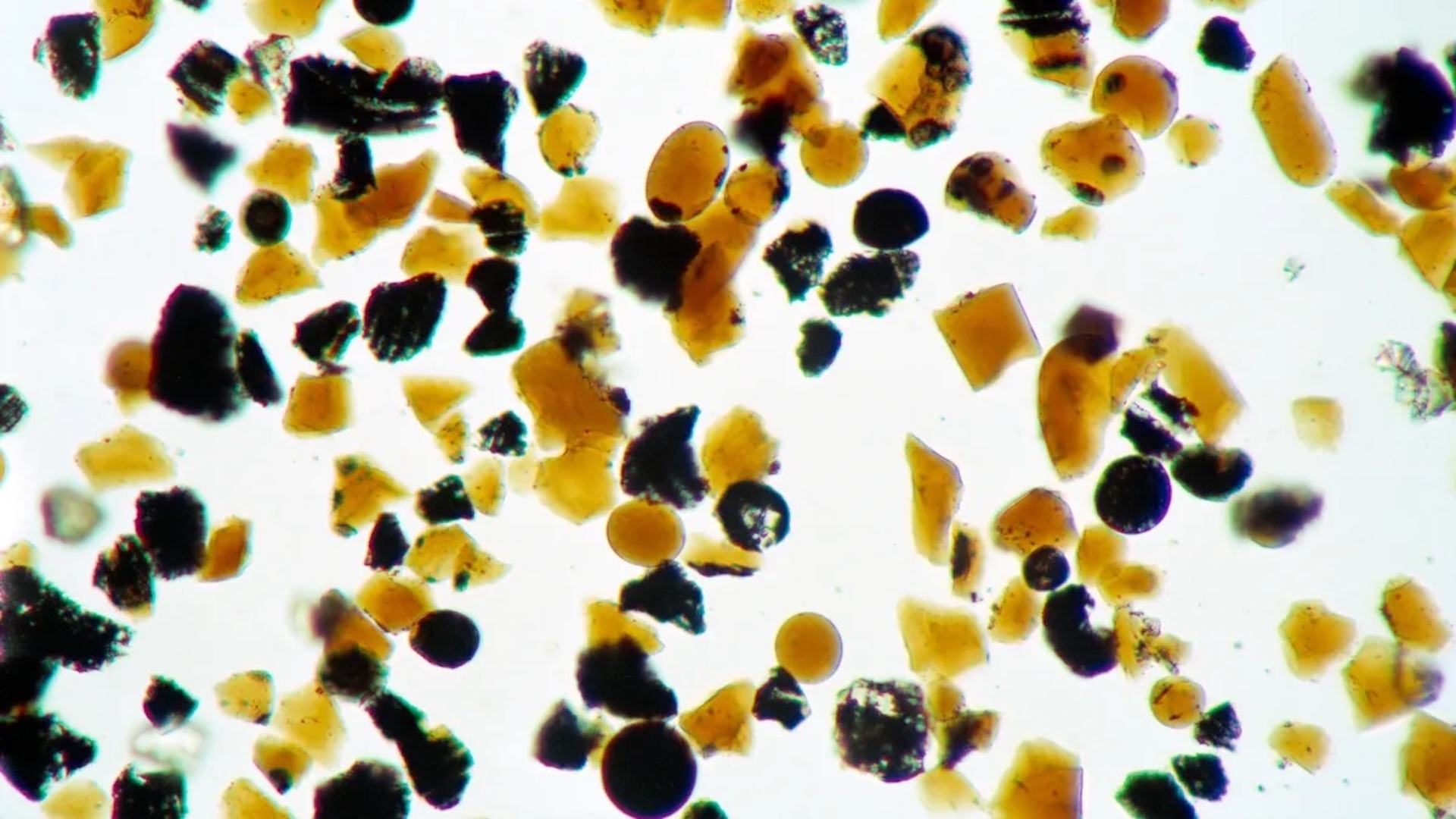

Jellyfish are gelatinous marine creatures that sting in response to pressure that activates venom cells lining the animal's tentacles. These venom cells, called nematocysts, deploy tiny, harpoon-like structures to inject their venom into the skin and then continue to hang on like a prickly burr. What the injured person does next is critical, because pouring the wrong liquid on the injury — something with a drastically different pH or salt balance — can cause the nematocysts on the skin to discharge more venom.

Related: Do bees really die if they sting you?

The urine-jellyfish myth is based on the idea that pee with its basic pH "could be more indicative of seawater," the nematocysts' natural environment, Richard Clark, medical director of the San Diego division of California Poison Control System, told Live Science. The rationale is that urine could rinse away the nematocysts without stimulating them, he said. But that's not what happens.

Since urine is often diluted, it can resemble fresh water more than seawater. And you never want to rinse a sting with fresh water, because it makes the pain worse. The dramatic difference in dissolved salt between fresh and seawater causes the nematocysts to release more venom. The same is true for urine. If it's too dilute, it will cause the nematocysts to keep firing.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The far better option is to just use seawater, Clark told Live Science. Studies have also shown vinegar (5% acetic acid) can neutralize nematocysts from some jellyfish species.

True jellyfish first aid can be surprisingly simple. Here are some better — and less disgusting — ways to manage discomfort after a jellyfish encounter, according to Colla.

- 1. Rinse with sea water or vinegar: Copious amounts of sea water is the best way to rinse the sting. Vinegar is also a reliable option for stings by most jellyfish species, helping to inactivate nematocysts and prevent further venom release. However, If the type of jellyfish is unknown, it's best to stick with sea water, Colla said.

- 2. Remove the tentacles: Removing tentacles and nematocysts is important to prevent further envenomation and pain. Do not try to scrape off the tentacles with your hands. Instead, carefully remove them with tweezers, then remove the nematocysts with the edge of something flat and stiff, like a credit card.

- 3. Seek medical attention: Some jellyfish stings can be severe or fatal. If you experience "swelling, nausea, confusion, body aches or difficulty breathing — see a doctor right away," Colla said. A sting from a box jellyfish (endemic to the Indo-Pacific region and Australia) may require antivenom medication.

This article is for informational purposes only, and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Donavyn Coffey is a Kentucky-based health and environment journalist reporting on healthcare, food systems and anything you can CRISPR. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired UK, Popular Science and Youth Today, among others. Donavyn was a Fulbright Fellow to Denmark where she studied molecular nutrition and food policy. She holds a bachelor's degree in biotechnology from the University of Kentucky and master's degrees in food technology from Aarhus University and journalism from New York University.