New Foot-long Tapeworms Identified

A major group of tapeworms, parasitic flatworms that can grow to more than 30 feet long in the digestive tracks of humans, fish and other animals while absorbing their nutrients, has been discovered by Canadian researchers.

The new tapeworm group, an order now dubbed Rhinebothriidea and that includes worms that parasitize stingrays and grow up to a foot long, was established as new to science by Claire J. Healy, a curator at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, and her colleagues.

Infection with a tapeworm is rare in the United States. People are often unaware they are infected, via an animal or water, but symptoms can include abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite and malnutrition. The treatment is a pill that kills the worm and helps the body expel it.

The discovery of the order Rhinebothriidea, which includes five genera new to science, represents a significant step forward in terms of understanding the evolutionary interrelationships of tapeworms, Healy said. The order is detailed in the March 2009 issue of the International Journal for Parasitology.

"This study illuminates an important part of the backbone of the tapeworm tree of life," Healy said. "It sets the stage for further research into the evolutionary relationships among tapeworms."

Catch-all category re-examined

The research started with a comprehensive study of a group of tapeworms that parasitize batoid fishes (stingrays and their relatives). Scientists previously had classified these worms classified within a subfamily of the Tetraphyllidea, an order that has lost credibility over the last two decades and is now viewed as a catch-all category for species that did not clearly fall within other orders, Healy said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

To clear things up, Healy and her colleagues obtained genetic sequences of 58 species of tapeworms, representing 30 genera in 5 tapeworm orders, the majority of these sequences having been obtained for the first time as part of this study.

Analysis of these data resulted in an evolutionary tree that strongly supports a lineage of tapeworms, including the study species, which is distinct from the Tetraphyllidea.

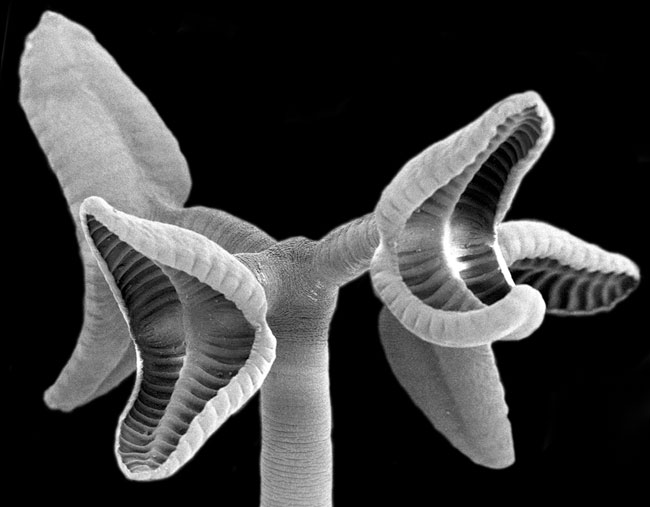

Using light and scanning electron microscopy, as well as histology, the research team found that the members of this lineage of tapeworms displayed physical characteristics that demonstrated a shared common ancestry.

Gripping details

Tapeworms use muscular pads or cups called bothridia to grip the surface of the host’s intestine. The bothridia in members of the newly identified lineage were borne on stalks, rather than being directly attached to the scolex (head part of body) proper. Based on this morphological feature, members of this lineage can be identified as belonging to the new order, the Rhinebothriidea, separate from the Tetraphyllidea.

The proposed new order includes 13 genera, five of which are new to science, having been discovered in the course of Healy and her colleagues' research.

More than 200 species, many of them undescribed, fall into this order with more being discovered as study continues. Future research on the Tetraphyllidea and its relatives may elucidate how these worms made the evolutionary transitions from marine to freshwater and terrestrial lifestyles.

- Maggot Therapy Gains in Popularity

- Video – The Dirt on Staying Clean

- Top 10 Mysterious Diseases