Maya Blue Paint Recipe Deciphered

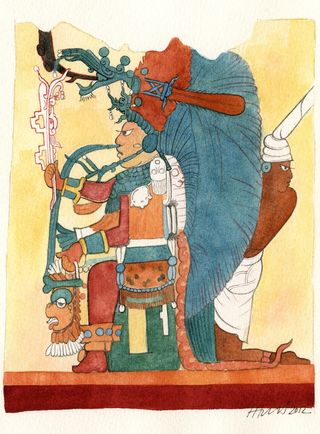

The ancient Maya used a vivid, remarkably durable blue paint to cover their palace walls, codices, pottery and maybe even the bodies of human sacrifices who were thrown to their deaths down sacred wells. Now a group of chemists claim to have cracked the recipe of Maya Blue.

Scientists have long known the two chief ingredients of the intense blue pigment: indigo, a plant dye that's used today to color denim; and palygorskite, a type of clay. But how the Maya cooked up the unfading paint remained a mystery. Now Spanish researchers report that they found traces of another pigment in Maya Blue, which they say gives clues about how the color was made.

"We detected a second pigment in the samples, dehydroindigo, which must have formed through oxidation of the indigo when it underwent exposure to the heat that is required to prepare Maya Blue," Antonio Doménech, a researcher from the University of Valencia, said in a statement.

"Indigo is blue and dehydroindigo is yellow, therefore the presence of both pigments in variable proportions would justify the more or less greenish tone of Maya Blue," Doménech explained. "It is possible that the Maya knew how to obtain the desired hue by varying the preparation temperature, for example heating the mixture for more or less time or adding more of less wood to the fire."

American researchers in 2008 claimed that copal resin, which was used for incense, may have been the third secret ingredient for Maya Blue. Their research was based on a study of a bowl that had traces of the pigment and was used to burn incense. But Doménech's team didn't buy those findings. [Image Gallery: Stunning Mayan Murals]

"The bowl contained Maya Blue mixed with copal incense, so the simplified conclusion was that it was only prepared by warming incense," Doménech said in a statement.

The Spanish researchers say they are now investigating the chemical bonds that bind the paint's organic component (indigo) to the inorganic component (clay), which is key to Maya Blue's resilience.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Among the more remarkable discoveries of the paint in context was a 14-foot thick (4 meters) layer of blue mud at the bottom of a naturally formed sinkhole, called the Sacred Cenote, at the famous Pre-Columbian Maya site Chichén Itzá in the Yucatán Peninsula of Mexico. When the Sacred Cenote was first dredged in 1904, it puzzled researchers, but some scientists now believe it was probably left over from blue-coated human sacrifices thrown into the well as part of a Maya ritual.

The research was detailed this year in the journal Microporous and Mesoporous Materials.

Follow Megan Gannon on Twitter and Google+. Follow us @livescience, Facebook & Google+. Original article on LiveScience.com.