Greenland Ice Sheet Holds Record of Fossil Fuels

Greenland's ice cores hide the chemical fingerprints of decades of fossil fuel burning, a researcher says.

Scientists have documented a decline in the levels of a nitrogen isotope (an atom of the same element with a different number of neutrons) called nitrogen-15 in layers of Greenland's ice sheet starting around the time of the Industrial Revolution, and a new study points to changes in acidity in the atmosphere as the culprit.

Increased acidity can be traced to sulfur dioxide, a byproduct of coal burning and a major cause of acid rain. Nitrogen-oxygen compounds, which are known as NOx and linked to high-temperature fuel combustion, also contribute to the buildup of acid in the atmosphere. And part of the chemical signature of NOx is an abundance of nitrogen-15.

Scientists say NOx from man-made emissions (such as those from coal-fired power plants and cars) likely carry more nitrogen-15 than NOx produced by natural sources, such as lightning-sparked forest fires. Therefore, the isotope levels in nitrate deposits (like those found in Greenland's ice cores) might be expected to go up after the onset of the Industrial Revolution. But Lei Geng, a University of Washington researcher, says those levels went down in the late 1800s because increasing sulfuric acid levels in the atmosphere allowed less nitrogen-15 to remain in vaporized nitrate.

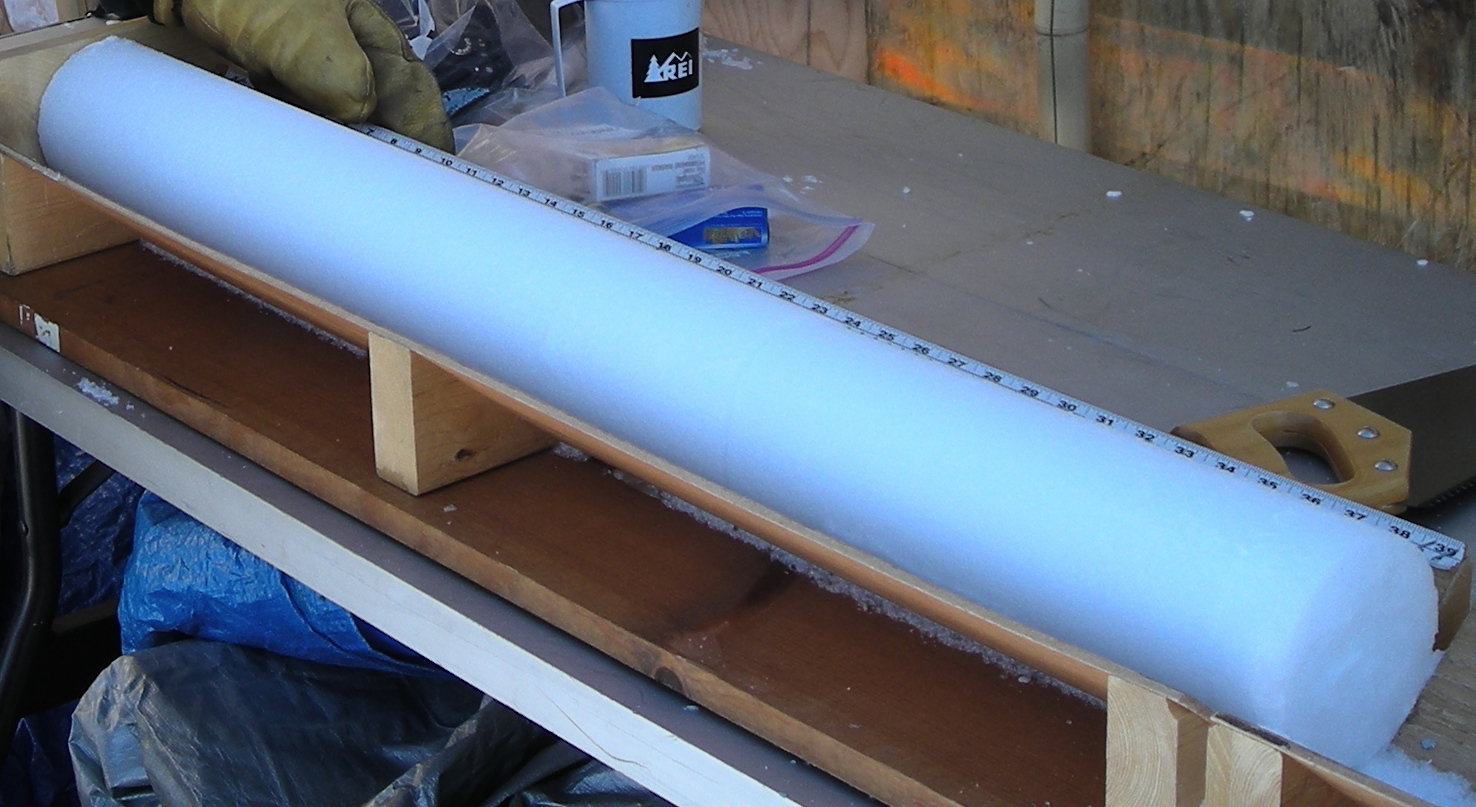

Geng said in a statement that the ice core he studied reveals a decline in NOx and sulfur dioxide emissions in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, followed by an increase up until the early 1970s, during a period of economic downturn and oil shortage for Western nations.

"We've seen a huge drop in sulfate concentrations since the late 1970s," Geng said. "By 2005, concentrations had dropped to levels similar to the late 1800s."

The Clean Air Act in the United States as well as a decrease in emission levels from individual vehicles may have contributed to this stabilization, Geng said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Geng presents these findings today (Dec. 7) at the fall meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience. We're also on Facebook & Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus