Warped Light Reveals Most Massive Distant Galaxy Cluster

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

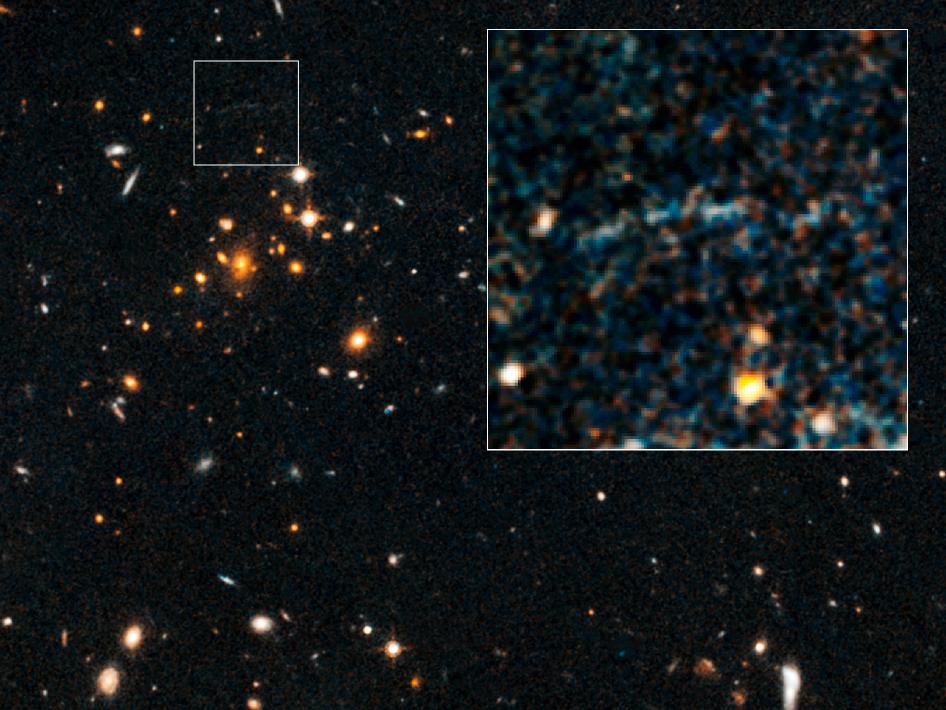

The most massive faraway cluster of galaxies has been found, thanks to a fortuitous astrophysical alignment that helped astronomers detect the mammoth grouping.

The galaxy cluster, named IDCS J1426.5+3508, is located a staggering 10 billion light-years away from Earth, and researchers spotted the behemoth because its gravitational field is so strong that it is warping the light coming from a galaxy behind it. Galaxy clusters are the most massive structures in our universe, and are made up of hundreds to thousands of galaxies that are bound together by gravity.

"When I first saw it, I kept staring at it, thinking it would go away," study lead author Anthony Gonzalez, an astronomer at the University of Florida in Gainesville, said in a statement. "The galaxy behind the cluster is a typical run-of-the-mill galaxy with a lot of young stars, but the galaxy cluster in front of it is a whopper for that range. However, it's really the way that the two systems are lined up that makes the occurrence truly remarkable."

This fluke alignment created what's called a gravitational lens, which occurs when a massive object, such as a black hole or galaxy cluster, lies directly between an observer (or telescope), and a more distant target in the background.

The powerful gravitational force of the object in the foreground warps the light being emitted by the more distant target, bending and twisting it on its path to the telescope.

Gravitational lensing from the faraway galaxy has never been observed behind a cluster at such an enormous distance, the researchers said.

Since this galaxy cluster is so distant — 10 billion light-years away — it existed when the universe was only one-quarter of its present age. The universe is estimated to be roughly 13.7 billion years old. Current theories for how the universe evolved suggest that relatively few of these galaxy clusters were present when the universe was in its infancy, the researchers said. [The Universe: Big Bang to Now in 10 Easy Steps]

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Still, finding this galaxy cluster represents a serendipitous astrophysical discovery in itself, since the astronomers were scanning only a small 9-square degree section of the sky. For comparison, if you extend your arm in front of you and hold up your index finger, you will be covering approximately 1 square degree of the sky with your finger, Gonzalez explained.

"So finding a massive cluster at that range that is also gravitationally lensing is a real long shot, even if you were looking at the whole sky," he said.

The astronomers originally found the galaxy cluster using NASA's infrared Spitzer Space Telescope, but evidence of the gravitational lensing was seen in images taken by the Hubble Space Telescope in 2010.

To follow up on this find, and to narrow down the cluster's mass and distance, the researchers used data from the Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-wave Astronomy (CARMA) radio telescope in the Inyo Mountains in California, and NASA's Chandra X-ray Observatory in space.

The discovery of a massive galaxy cluster at such a great distance, in a limited field of observation, could indicate that current models of clusters in the early universe may need to be reworked, Gonzalez said. But right now, it is too soon to tell.

"We just don't know," Gonzalez said. "We need to find more clusters at this range so that we can get more data. So far we only have one example to study."

The study's detailed findings are published in the July 10 issue of The Astrophysical Journal.

This story was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. Follow SPACE.com on Twitter @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus