The Profound History of Coins

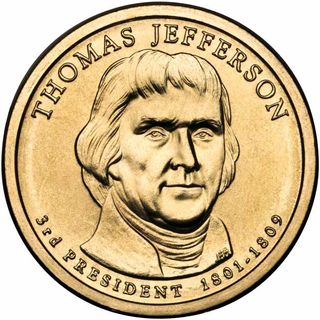

More than 1.4 billion $1 coins featuring the likenesses of U.S. presidents from George Washington to James Garfield sit in a warehouse in Washington, D.C. Few people even know they exist.

The coins are part of a series the United States Mint started in 2007. The program was discontinued in 2011 because nobody was apparently interested. Coins featuring other presidents have been minted for collectors, but most of them have not been circulated.

Americans are attached to their paper bills, and prefer using them instead even if it costs the government more money.

It's a far cry from the social and political upheaval caused by the introduction of the first coins more than 2,500 years ago, said Tom Figueira, professor of Classics at Rutgers University in New Jersey.

"Mental changes with the introduction of coins were profound," Figueira said. "It was a whole new way of thinking about value."

The first coins

The world's first coins appeared around 600 B.C., jingling around in the pockets of the Lydians, a kingdom tied to ancient Greece and located in modern-day Turkey. They featured the stylized head of a lion and were made of electrum, an alloy of gold and silver.

The concept of money had been around awhile. Shells were used as currency in ancient China and, about 5,000 years ago, Mesopotamians had even developed a banking system where people could "deposit" grains, livestock and other valuables for safekeeping or trade.

But it wasn't until the actual coins appeared—money for money's sake—that the social effects of having a currency really started to take hold, Figueira explains. Keeping things tidy in a society that had gradually become very complex was the catalyst for minting those first pieces, he thinks.

"Coins allowed the processes of city-states to be organized in a way that was elegant and just," Figueira told LiveScience. "They made people feel that things like war subsidies were orderly and transparent."

Greek labs

Shiny new coins began sprouting up throughout the Mediterranean just a few decades later, as the Lydian experiment appeared to be going well.

"It's pretty clear that it worked," Figueira said, "and Greek city-states were a laboratory for all kinds of social experiments like this."

Athens, Aegina and Corinth and Persia all developed their own coins by the 6th-century B.C, expanding trade networks with a newfound ease. Gold and silver replaced electrum as the material of choice, with coin values reflecting the actual value of the metal and not an arbitrary amount imposed on the coin, as in the case with modern currencies. Roman and then Celtic coins later followed the same traditions.

Coins provided social mobility to those who didn't have it, everywhere they appeared. People could move around with something to show for it, aside from just the clothes on their backs, Figueira said.

There were some early kinks to iron out, said Figueira, mostly to do with the sheer variety of coins around Europe. The majority of cities had their own design to reflect local pride.

"The pictures were a way to communicate social solidarity," he said, "letting people know who we are, who our heroes are." Romans commemorated their emperors, while the Celts engraved their money with runes, animals and important kings.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.