Censorship of 16th-Century Big Thinker Erasmus Revealed

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

More than 400 years before modern-day governments tried shutting down blogs or blocking tweets, two people tasked with censoring a sometimes-critic of the Catholic Church in Renaissance Europe took to their duties in very different ways: one with great beauty, the other with glue and, it appears, a message.

Now, two books, housed at separate libraries at the University of Toronto, illustrate two unusual approaches censors took when dealing with the same author, Erasmus.

Born in Rotterdam around 1466, Erasmus was a prolific writer who sought out wisdom in ancient Greek and Latin texts. His writings, mass produced thanks to the printing press, were at times critical of the Catholic Church.

By the time he died in 1536 the church was breaking apart, with splinter groups known as Protestants coming into conflict with the Catholics. English king Henry VIII was one of the most famous examples of a Protestant, creating a Church of England separate from church authorities in Rome. [In Photos: A Journey Through Early Christian Rome]

The conflicts that ensued between Catholics and Protestants were fought, not just with guns and swords, but with ideas, especially the printed word. Erasmus was considered by some to be a Protestant sympathizer, and in 1559 his texts were put on a Roman index of forbidden books. Both sides tried to censor each other whenever they could, with the Catholics being somewhat more effective, at least during the 16th century.

"They had the agents to be able to do it," said Pearce Carefoote, a librarian at the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto and author of "Forbidden Fruit: Banned, Censored, and Challenged Books from Dante to Harry Potter" (Lester, Mason & Begg, 2007).

"Protestants didn't have that same ability in the 16th century," Carefoote added, noting that Protestantsdidn't have the same level of organization.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Censoring with glue ... and words

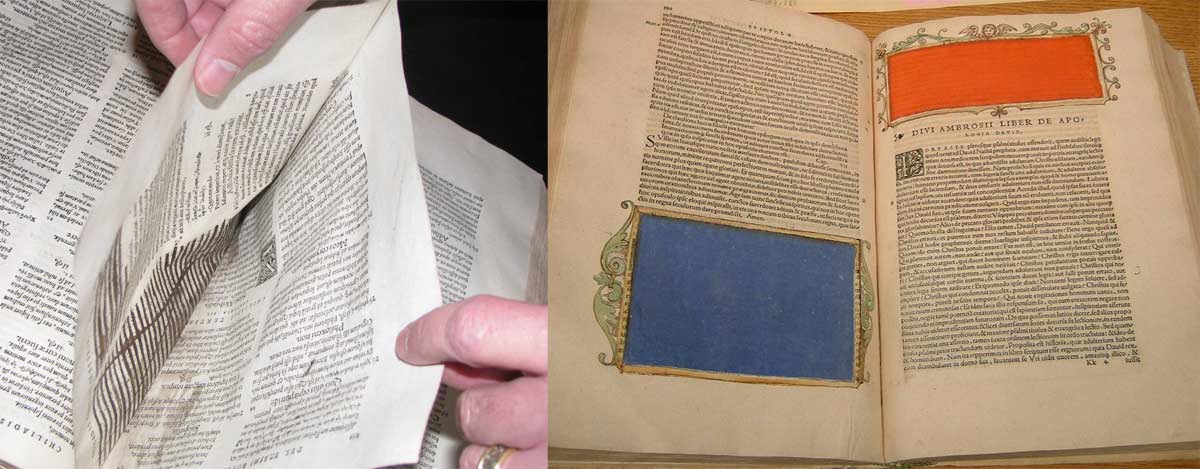

One book, "Adagorium," was published in 1541 in Lyon, France, and was cataloged this month in the Thomas Fisher Library. The book contains ancient proverbs written in Latin and Greek along with commentary by Erasmus.

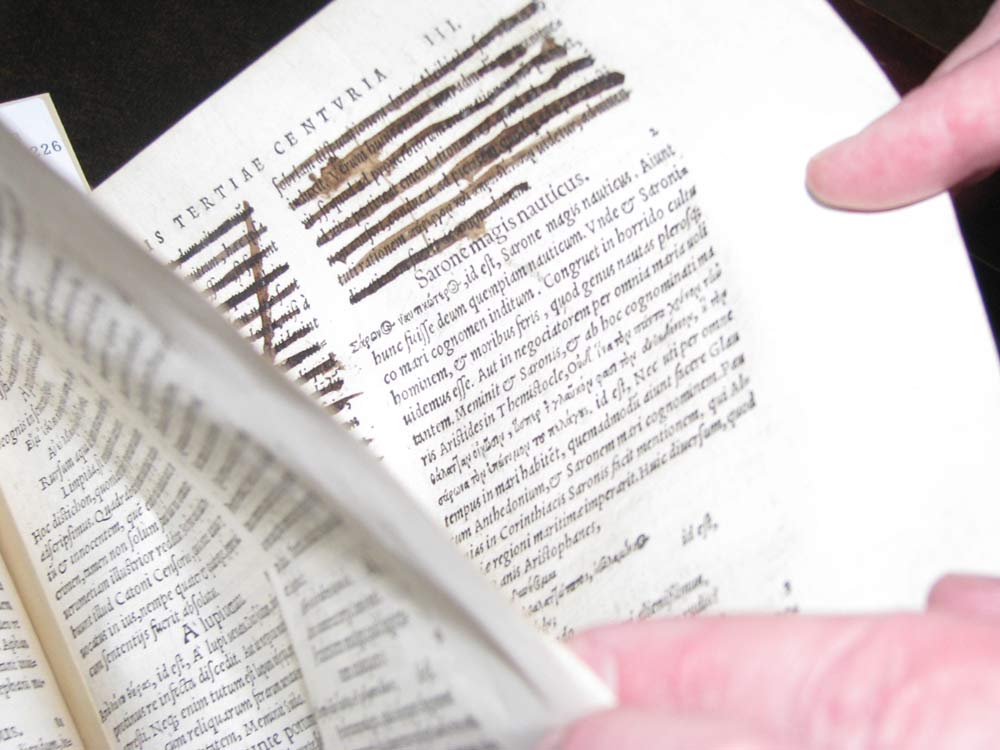

Parts of it are blotted out with ink, a practice not unusual for the time. However, one section was treated with particular disdain, having pages ripped out, sections inked out and two of the pages actually glued together, still stuck after more than 400 years. [See Photos of the Censored Books]

"They've censored it, and then just to make sure they glued the page together," Carefoote told LiveScience. "This is the first time I've ever seen that (the use of glue)."

If that wasn't enough, the censor appears to have left a message on the front, written in Latin, blasting Erasmus. It reads (in translation), "O Erasmus, you were the first to write the praise of folly, indicating the foolishness of your own nature." One of Erasmus' works was called "The Praise of Folly."

Carefoote cautioned that the message could've been written by another person, though the ink seems to match that of the censor. From the style of writing Carefoote thinks the censorship may have occurred late in the 16th century but more research is needed to firm up that date.

Erasmus' ideas on war seem to have gotten lots of ink; that section of the book begins with the adage "Dulce bellum inexpertis," or "war is sweet to those who haven't experienced it." The censorship starts out slow at first with just a sentence blotted out here and there, but picks up later with entire sections being inked over. Carefoote suspects some Catholics would not have been amused by these ideas on war.

"He would not have gone along with the basic 'just war' theories that the scholastics (a group of thinkers) had developed," Carefoote said of Erasmus. [The History of Human Aggression]

After it was censored, the book was likely kept in a restricted library called an inferno, Carefoote suggests. That would've made reading it difficult. "Say this was kept in a cathedral library, in a Catholic town, what you would have to do is, you would have to put in a petition to one of the church officials," he said. "They would examine your reasons for why you need to see this book and they would give permission to let you read it."

The book was bequeathed to the library by the late Ralph Stanton, an avid collector of books and a mathematics professor at the University of Waterloo in Canada.

Censoring with beauty

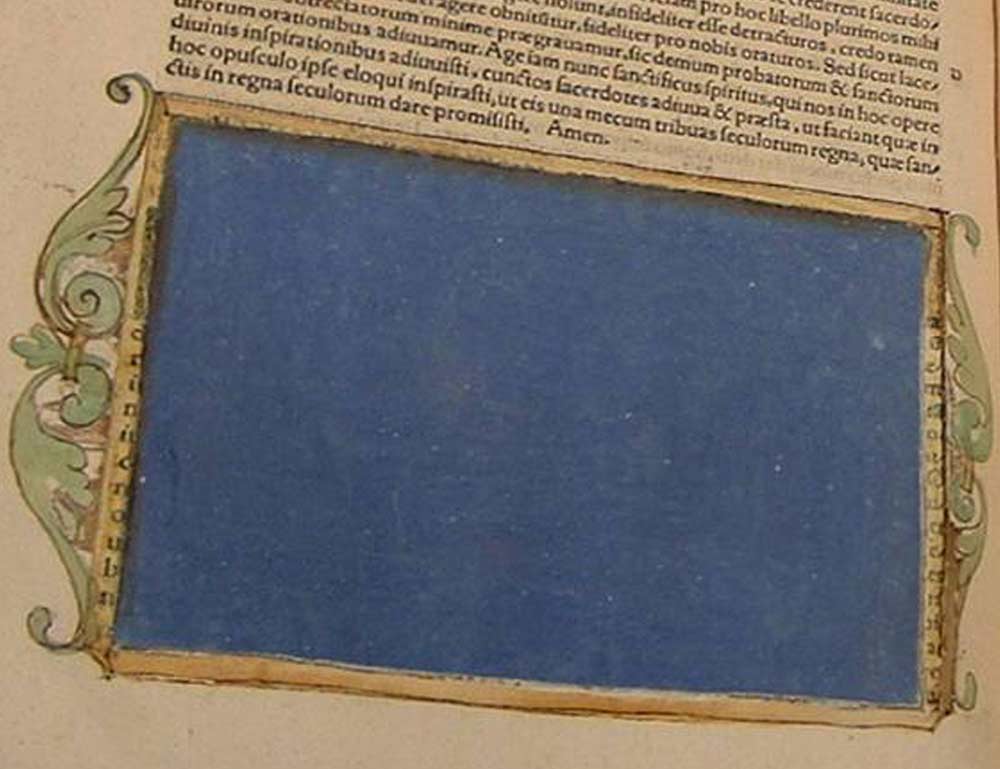

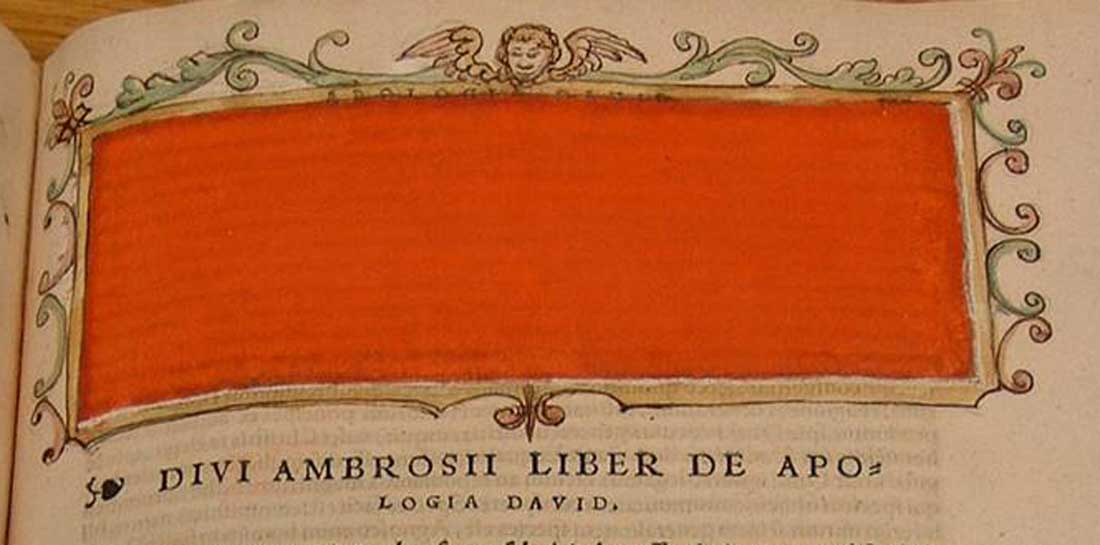

In contrast to the newly discovered glued-up book, another example of Erasmus' writing, held at the Centre for Renaissance and Reformation Studies at the University of Toronto, reveals a censor who took to his task with an artistic flourish.

Published in Basel, Switzerland, in 1538 this book contains essays by Erasmus introducing the writing of St. Ambrose, a fourth-century saint who was the bishop of Milan.

"It is one of the most exquisitely beautiful examples of censorship, with the offending passages obliterated using vibrant watercolors framed in baroque scroll frames with attending putti (an image of a male child)," Carefoote writes in his 2007 book. While the censor blanked out the prefaces by Erasmus he left the saint’s work alone. It's not known what Erasmus said that got him censored.It's also not known why the censor, probably a librarian, approached his job with such artistry.

"You have some librarians who just love books and so it could have been that the book itself he wanted to preserve in as good a state as he possibly could, so therefore he complied with the law but he did it in such a way that it was not offensive to the book," Carefoote said.

Or perhaps, deep down, the censor actually sympathized with Erasmus' work. "Maybe he sympathized with Erasmus and so he wasn't going to the extremes that (the other person) did," Carefoote added.

Whatever the reasons, these censors have left researchers with two remarkable 16th-century artifacts, now within walking distance of each other. Two works by the same author, both of which were censored, one with glue and the other with artistic beauty.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus