A failed Russian Mars probe came crashing back to Earth Sunday (Jan. 15) in a death plunge over the Pacific Ocean, according to Russian news reports.

After languishing in Earth orbit for more than two months, the 14.5-ton Phobos-Grunt spacecraft fell at around 12:45 p.m. EST (1745 GMT) Sunday, apparently slamming into the atmosphere over a stretch of the southern Pacific off the coast of Chile, Russian officials told the Ria Novosti news agency.

"Phobos-Grunt fragments have crashed down in the Pacific Ocean," Alexei Zolotukhin, an official with Russia's Defense Ministry, was quoted by Ria Novosti as saying. Zolotukhin said that the spacecraft crashed about 776 miles (1,250 kilometers) west of the island of Wellington, the news agency reported.

Before the crash, Russia's Federal Space Agency, known as Roscosmos, released a map that estimated a potential crash zone in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean sometime between 12:50 p.m. and 1:34 p.m. EST (1750-1834 GMT) on Sunday.

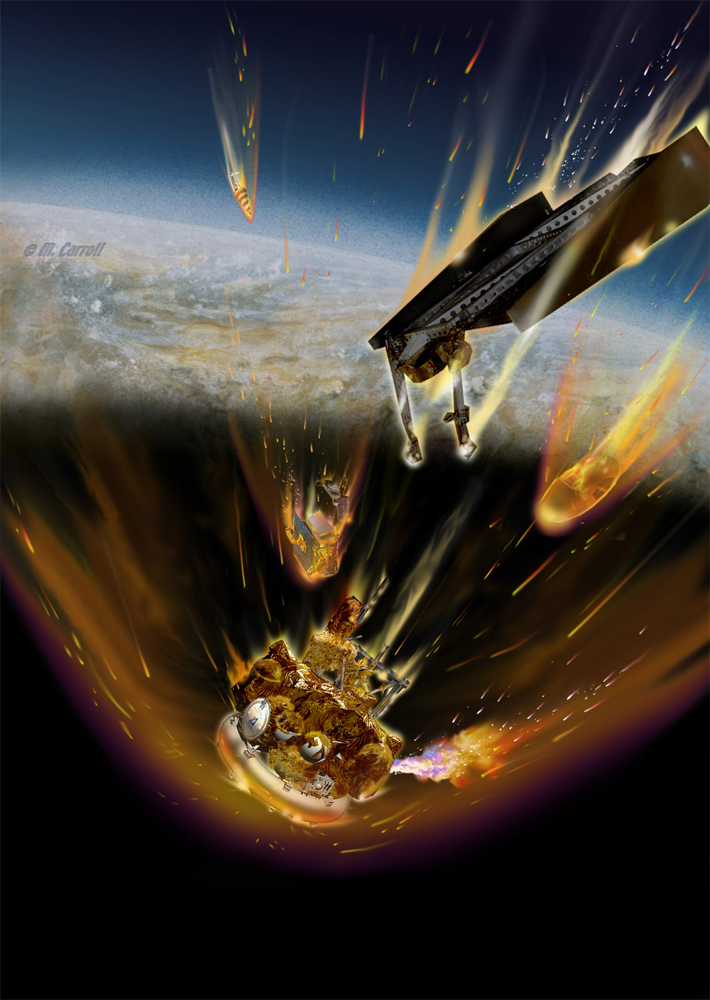

The huge probe likely broke apart as it re-entered, with the vast majority of the pieces burning up in the atmosphere, but some big componets were expected to survive the fiery fall. At the moment, it's not clear how many chunks of Phobos-Grunt survived, or exactly where this hail of hardy debris touched down.

Roscosmos had estimated that 20 to 30 chunks of Phobos-Grunt, weighing a total of no more than 440 pounds (200 kilograms), might hit the Earth's surface. Officials also stressed that the probe's huge reservoir of toxic fuel would burn up high over Earth. [Photos of the Phobos-Grunt mission]

While it can be tough for observers in the West to vet such claims from the Russians, fears that Phobos-Grunt's fall would cause dangerous chemicals to rain from the sky are probably unfounded, experts say.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They did acknowledge early on that the [fuel] tanks are made of aluminum," Nick Johnson, chief scientist of NASA's Orbital Debris Program Office at the Johnson Space Center in Houston, told SPACE.com. "Aluminum rarely survives re-entry, so there's no reason to really doubt them."

Russian officials have also repeatedly stated that there's little danger of contamination from a tiny amount of radioactive material onboard Phobos-Grunt, about 10 micrograms of Cobalt-57 that forms part of a science instrument on the craft.

Failed mission to Mars

The crash marked a dramatic end to Phobos-Grunt's brief and troubled life. The $165 million probe launched Nov. 8 on a mission to collect soil samples from the Martian moon Phobos and send them back to Earth in a return capsule ("grunt" means "soil" in Russian).

Phobos-Grunt's main engines were supposed to fire shortly after liftoff to send the spacecraft on its way to the Red Planet. That never happened, however, and the probe got stuck in Earth orbit.

Russian officials still aren't sure what went wrong. They hinted recently that some form of sabotage may be responsible for Phobos-Grunt's problems, and perhaps for the other four embarrassing space failures Russia suffered in 2011 as well.

Phobos-Grunt was also carrying China's first attempt at a Mars orbiter, along with an experiment run by the United States-based Planetary Society designed to study how a long journey through deep space affects micro-organisms.

China wrote off its orbiter, a tiny craft called Yinghuo-1, as a total loss in mid-November. But the Planetary Society has said that its project — the Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment, or LIFE — may survive re-entry, since it was tucked inside Phobos-Grunt's return capsule.

It may even be possible to salvage some science out of LIFE, researchers say, but only if the return capsule survives and is recovered.

The sky is falling

Phobos-Grunt's fall may add to a growing perception that the sky is falling, for it was the third uncontrolled re-entry of a big spacecraft in the last four months.

NASA's 6.5-ton UARS satellite came down in September, and the 2.7-ton German satellite ROSAT followed one month later. Both crashed over stretches of empty ocean, causing no casualites. (Nobody is known to have ever been injured by a piece of man-made space debris.)

While they're temporally linked, the three spacecraft falls differ in significant ways. UARS and ROSAT, for example, were decommissioned satellites that finished their science work years ago and then spiraled downward in slowly decaying orbits. Phobos-Grunt, by contrast, lived fast and died young without accomplishing its mission.

Also, Phobos-Grunt was much heavier than either UARS or ROSAT. At 14.5 tons, the Russian Mars probe was the most massive satellite to fall uncontrolled to Earth since NASA's 85-ton Skylab space station in 1979.

Russia's 135-ton Mir space station remains the largest single man-made object to re-enter our atmosphere. Engineers de-orbited Mir in a controlled fashion in 2001.

This article was provided by SPACE.com, a sister site to LiveScience. You can follow SPACE.com senior writer Mike Wall on Twitter: @michaeldwall. Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.