A Graying Population Reduces Global Warming

You can help the environment by getting old. A demographer has profiled the relationship between age and a person's carbon dioxide emissions, showing that after retirement age, our individual contributions to global warming decline.

"We expect age structure in the longer term to reduce carbon dioxide emissions," said Emilio Zagheni, a research scientist with the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research in Germany, who conducted the study."This study is specifically for the United States, but the trend is expected to hold at the global level."

The importance of age

Population factors heavily into greenhouse gas-emission projections, however, the influence of the age composition of a population is not included in calculations, like those used by the U.N.'s International Panel for Climate Change. This was part of the motivation for the research, Zagheni said.

The age of the U.S. population is changing; the past four censuses have shown steadily increasing numbers of Americans heading into the 65-and-older category. This segment of the global population is also growing.

Societies with growing elderly populations and consumption patterns similar to the U.S. may see their carbon dioxide emissions drop, Zagheni's research suggests.

But in the U.S., this reduction won't show up immediately. Zagheni estimates that until about 2050, the aging of the U.S. population will, on average, cause our carbon dioxide emissions to rise slightly.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The green elderly

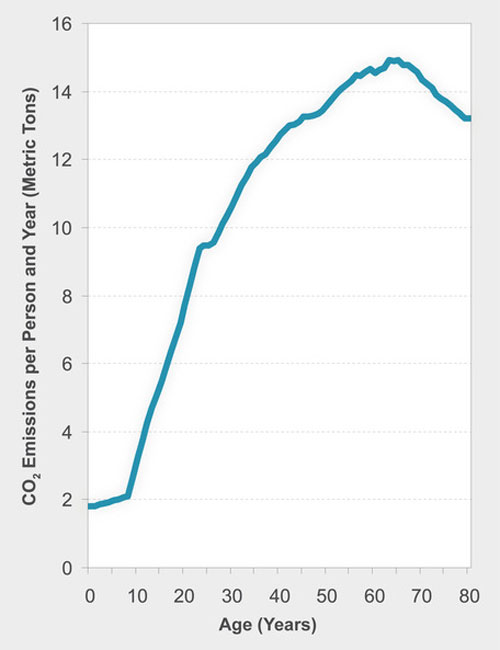

Using data available for U.S. residents, Zagheni compiled how much Americans of different ages spend on nine energy-intensive products and services, including electricity, gasoline and air travel. He then assigned carbon dioxide emissions weights to these and combined them into a single carbon dioxide emissions profile.

He found that as they age, Americans consume more and more of these things, producing more carbon dioxide as a result. This trend peaks around age 65, and then much of it reverses. Older people tend to spend more on their health, which generally produces lower levels of greenhouse gas emissions. This also reduces the money they have to spend on other, more energy-intensive things.

However, since they are spending more time at home, the use of electricity and natural gas continues to rise among people until they reach 80.

A delay

However, aging is expected to continue to increase emissions for at least several decades, perhaps until 2050, according to a model Zagheni created of an aging, but not growing, U.S. population.

This is because the last members of the post-World War II population bulge, the Baby Boomers, will hit retirement age around 2030. As they continue to age in the years afterward, they will contribute less and less to carbon dioxide emissions, and eventually that reduction will become noticeable. However, rising life expectancy will mean more older people, and so this is expected to contribute to short-term increases in carbon emissions, according to Zagheni. [7 Population Milestones]

He also investigated the effect of population growth in the U.S, and found it will more than counteract aging and will increase emissions overall.

"However, thanks to the changing age structure, in the long term emissions will not increase as much as we would expect based on population growth only," he wrote in an email to LiveScience.

Zagheni's research appears in the journal Demography.

You can follow LiveScience senior writer Wynne Parry on Twitter @Wynne_Parry. Follow LiveScience for the latest in science news and discoveries on Twitter @livescience and on Facebook.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus