Fallen Stars: A Gallery of Famous Meteorites

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

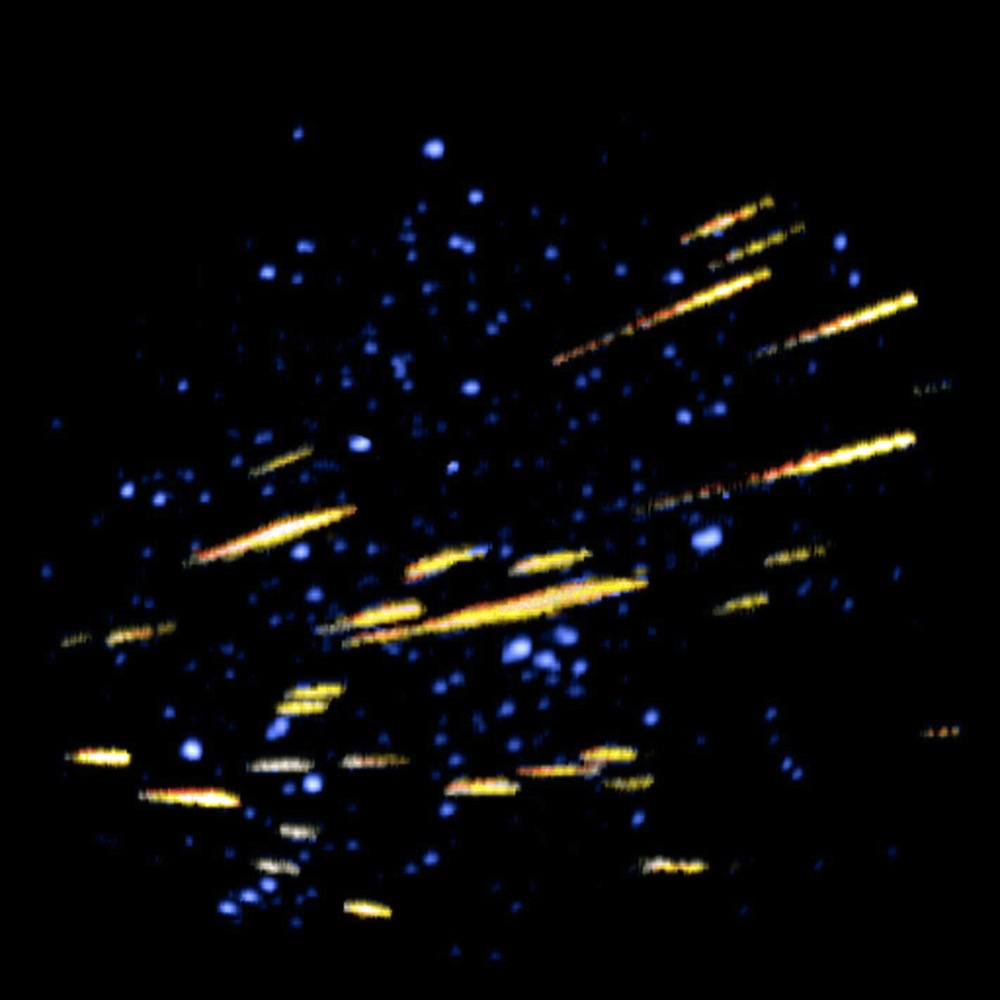

Stones from the Sky

Earth gets alien visitors all the time, in the form of space debris that makes it through our atmosphere. The terms can be confusing, so here's a glossery: Meteoroids are defined by the International Astronomical Union as "a solid object moving in interplanetary space, of a size considerably smaller than an asteroid and considerably larger than an atom." When a meteoroid enters a planet's atmosphere, its bright path across the sky is called a meteor. When a meteor makes it through the atmosphere without burning up entirely, the remnants found on earth are called meteorites.

Above, a meteor outburst during the Perseid meteor showers of 1995. Friction in the atmosphere turns rocks into fireballs.

Allende Meteorite

This 3-inch (8 centimeter)-wide meteorite fragment is part of the Allende meteorite, the most-studied meteorite ever. This car-sized chunk of rock flamed through Earth's atmosphere in February, 1969. It broke into thousands of smaller pieces, found strewn over the desert in the northern Mexico state of Chihuahua.

The Allende meteorite is a carbonaceous chondrite, a rare type of meteorite that makes up only about 4 percent of known meteorites. The Allende meteorite contains components that are more than 4.5 billion years old, making the rock a snapshot of the conditions present in the earliest days of the solar system.

Car Crash

Not every meteorite falls in a near-empty desert. The Peekskill meteorite crashed into this unlucky car in New York in 1992. The meteorite itself was unremarkable, but more than a dozen people caught its entry into the atmosphere on video, providing scientists with a plethora of data on the meteorite's behavior before it hit the ground.

The car has found fame, too. It's now owned by R.A. Langheinrich Meteorites, and has been put on display around the world.

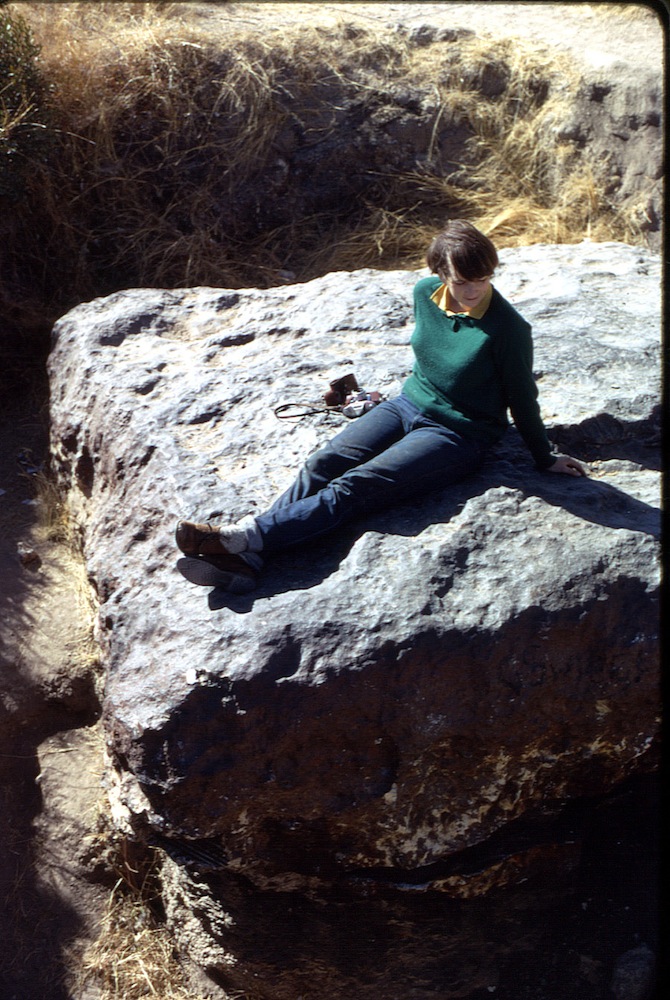

Moon Meteorite

Until the 1980s, scientists believed that all meteorites came from the asteroid belt between Mars and Jupiter. This white-speckled rock changed all that. Researchers found it in Antarctica in 1981 and noticed its similarity to the moon rocks that Apollo astronauts brought back to Earth. Sure enough, tests showed that this rock came from the moon. In the next 15 years, 11 other moon rocks would be found on Earth.

Willamette Wonder

The Willamette meteorite is the largest ever found in North America. A settler named Ellis Hughes found the meteorite in Oregon in 1902 and moved the 15.5-ton iron rock to his own property. It wasn't the meteorite's first terrestrial journey: Because no impact crater was found at the meteor's original resting site, researchers suspect it landed elsewhere and was transported to Oregon via glacial action during the Ice Age. The meteorite is now on display at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Buried Iron

The Hoba meteorite in Namibia is the largest-known single meteorite piece on Earth. A farmer discovered the gigantic iron mass while plowing his field in the early 1900s. It was soon excavated and estimated to weigh about 66 tons. Because of its huge mass, the meteorite has never been moved.

Tagish Lake

In January 2000, a meteoroid exploded over Tagish Lake in southwestern Canada, scattering the frozen lake with at least 22 pounds (10 kg) of meteorites. A June 2011 study published in the journal Science found significant geological variation among fragments, with some containing amino acids and other biochemical building blocks of life.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

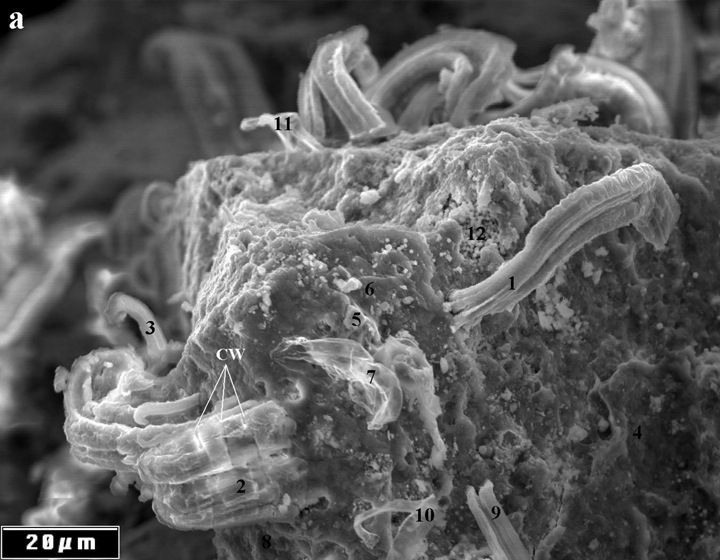

Life in a Meteorite?

The Orgueil meteorite fell in France in 1864 and caused a firestorm in scientific circles in 2011. NASA scientist Richard Hoover claimed in March 2011 in the Journal of Cosmology that filaments in the meteorite, seen under a scanning electron microscope, could be evidence of extraterrestrial bacteria.

Other scientists, however, called foul, pointing out that the structures could be created by non-organic processes.

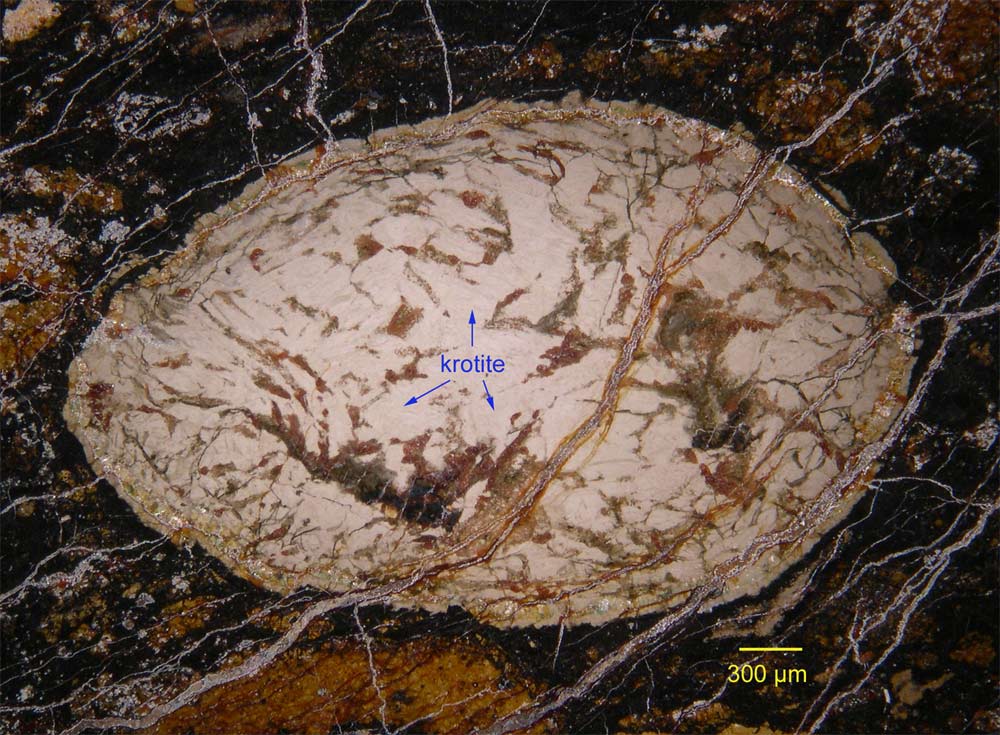

Old Rock, New Mineral

Occasionally, meteorites bring something new to Earth. This 4.5-billion-year-old meteorite landed in northwest Africa. Inside, scientists discovered a mineral called krotite, which had never been found in nature before. Krotite forms at high temperatures and low pressure, and was likely one of the first minerals in the newly emerging solar system.

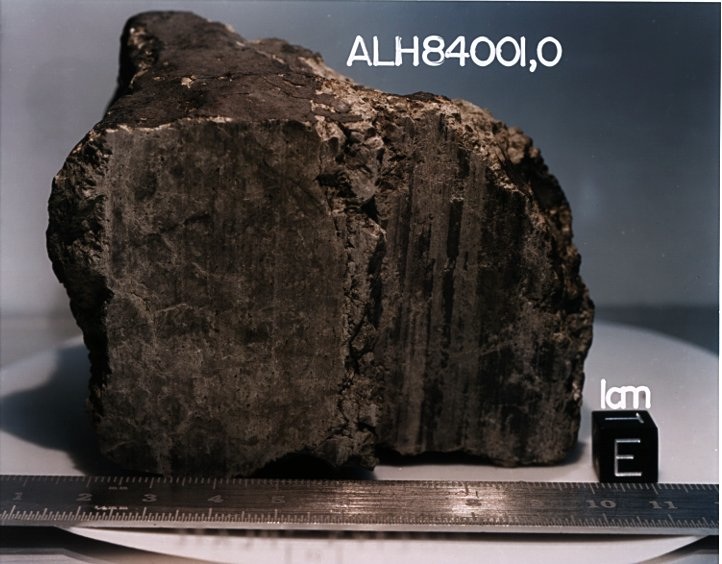

Martian Meteorite

Another controversial chunk of rock, this meteorite from Mars was found in 1984 in the Allan Hills ice field in Antarctica and dubbed ALH84001. In 1996, researchers announced in the journal Science that structures in the meteorite might be fossilized microbial life, setting off the kind of media storm that you'd expect from a story about potential life on Mars. But most scientists remain skeptical that the Allan Hills specimen is evidence of life, and studies since 1996 have been unable to conclusively prove that the original claims are true.

Otherworldly Meteorite

Earth isn't the only planet with alien rocks. NASA's Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity found this iron meteorite on the Red Planet, the first meteorite ever found on another world.

The basketball-sized rock, dubbed "heat shield rock" because it sits near the debris of Opportunity's heat shield, is mostly nickel and iron.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus