11,500-Year-Old Remains of Cremated 3-Year-Old Discovered

An archaeological dig in Alaska has uncovered the oldest human remains ever found in Arctic or Subarctic North America – the cremated skeleton of a 3-year-old.

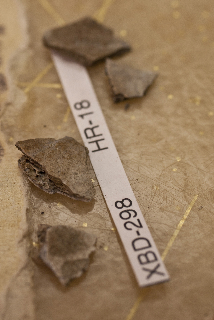

The chlid's burned bone fragments were found in a fire pit in the remains of an ancient house near the Tanana River in central Alaska. Researchers date the cremation to 11,500 years ago. After the child's body was burned, researchers report in the Feb. 25 issue of the journal Science, the house and hearth were buried and abandoned.

"The fact that the child was cremated within the center of the house … this was an important member of society," said study author Ben Potter, an archaeologist at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Cooking and cremation

The child's remains aren't the only thing about the find that excites Potter and his colleagues. The Paleoindian inhabitants of Alaska left few structures behind; usually, archaeologists discover outdoor hearths and specialized tools that suggest temporary work sites or hunting camps. The house that became a child's grave is the first house structure found from this time period in northern North America. The most similar site found is on the Kamchatka Peninsula in far eastern Russia, Potter said during a press conference.

The cremated child lived and died at the very end of the "last cold snap of the last Ice Age," Potter said. The Bering Land Bridge that once connected eastern Siberia and Alaska still may have been open, or was only recently inundated by rising sea levels. The newly discovered house sits in an area called the Upward Sun River site, which would have been well vegetated, Potter said. The inhabitants stoked their cooking fires with poplar wood.

Within the fire pit, the researchers discovered the cooked bones of small animals, including salmon, rabbits, ground squirrels and birds. The presence of salmon (and young ground squirrels), peg the site as a summer settlement, Potter said. The presence of the child, who could have been as young as 2 or as old as 4 based on the development of the adult teeth, suggests that women were present as well, said study researcher Joel Irish, a dental anthropologist at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"In prehistoric times, weaning would come as late as maybe 3 years old," Irish said. "So this child was probably still breastfeeding."

The researchers also found four used stone tools at the site, along with stone flakes left over from tool-sharpening.

Native son (or daughter)

By sifting through the layers in the fire pit, the researchers were able to reconstruct the house's inhabitants' summer. They fished and hunted small game, either cooking it in the hearth or disposing of bones and other leftovers there. When the child died, he or she – researchers can't say for sure, though they're hoping to find out – was placed on his or her back in the hearth and burned for one to three hours.

The child's cremation site may have been a former cooking pit, but Potter and Irish don't suspect cannibalism. The child's body wasn't disturbed during the burn, they said, and no limbs were carted off to the dinner table. The house's foundation was filled in after the cremation, suggesting a respectful burial, Potter said.

The child's cause of death can't be determined, and only about 20 percent of the skeleton survived the fire (Potter first realized he'd found human remains when he uncovered a molar tooth). The teeth do provide some clues as to the child's ancestry, Irish said. He or she had shovel-shaped front teeth, a genetic trait common in northeast Asian and Native American populations.

"This child does have some affinity to native populations," Irish said.

As such, the researchers worked with native groups in every step of the scientific process. When Potter found the first molar, he immediately halted the dig to consult with local native communities and the owner of the land. The researchers plan to try to extract DNA from the bones, both to see if they can tell the child's gender and to see if they can genetically link him or her to living or ancient native populations. What will happen to the bones after that has not yet been decided, Potter said.

The find is a "very significant discovery and contribution to North American archaeology," said E. James Dixon, an anthropologist at the University of New Mexico who was not involved in the dig. The find fits a pattern, Dixon said, in that 25 percent of remains found that are older than 10,000 years are children.

"It suggests that there is a relatively high infant mortality rate across North America at the time, and this reinforces that pattern," Dixon told LiveScience.

The child's young age hit close to home for the research team, Potter said.

"We both have young children around the same age," Potter said of himself and Irish. "That was quite remarkable for both of us to be thinking, beyond the scientific aspect, that yes, this was a living breathing human being that died."

You can follow LiveScience Senior Writer Stephanie Pappas on Twitter @sipappas.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.