Ancient 8-Foot Sea Scorpions Probably Were Pussycats

Ancient sea scorpions included the largest and arguably most frightening bug-like creatures known to have lived on Earth, but despite their fearsome claws, these giants might actually have been creampuffs, scientists think.

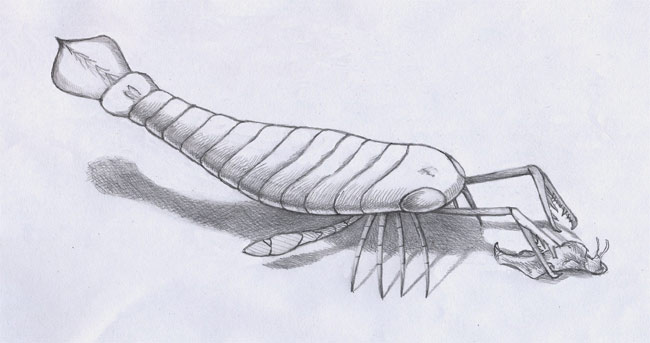

Sea scorpions, known as pterygotid eurypterids, were arthropods, a group that includes insects and crabs. Though not actually scorpions, many of the animals had tails ending in spikes, hence the name.

These monstrous pterygotids were believed to be terrors of the seas 470 million to 370 million years ago, long before the dinosaurs appeared, reaching more than 8 feet (2.5 meters) long with large claws laden with sharp spines. [Dangers in the Deep: 10 Scariest Sea Creatures]

"We have a group that in many cases was perceived as big, bad animals, sort of the Tyrannosaurus rex of the seas of their time," researcher Richard Laub, a paleontologist at the Buffalo Museum of Science in New York, told LiveScience. "Frankly, that was my view when we began our work."

Now, however, Laub and his colleagues in New York and New Jersey find these claws might not have possessed much crushing power at all.

"Our results derail the image of these imposing-looking animals, the largest arthropods yet known to have existed, as fearsome predators," Laub said. "It opens the possibility that they were scavengers or even vegetarians."

The scientists analyzed claws from a group of one of the largest sea scorpions, Acutiramus, which lived about 416 million to 419 million years ago in what is now New York and Ontario, Canada. They calculated that the pincers could only safely apply no more than 5 newtons of force without damaging themselves. This would make them incapable of penetrating even a medium-size horseshoe crab's armor, which needs 8 to 17 newtons to crack open. (For comparison, research has suggested T. rex's lower jaw could apply 200,000 newtons of force, or enough strength to lift a tractor-trailer.)

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

As such, the pincers could not have attacked anything with a hard shell, or any creature that could have put up a significant struggle.

"These impressive claws could not have functioned as I and others had thought," Laub said.

Moreover, the absence of an "elbow joint" between the claws and the body of Acutiramus would have limited claw movement. This would have made it better at grasping prey on the seafloor than at hunting anything fleeing fish or other swimming creatures.

"I have long been suspicious of prevailing popular interpretations," said paleobiologist Roy Plotnick at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who was not involved in the study. "This is a welcome contribution that strongly supports an alternative interpretation of claw function."

"What always worried me about their claws was that their little barbs never looked as if they were strong enough to grab anything really hard or muscular," Plotnick said in an interview. "I don't question that they could have been used in a predatory manner, but they certainly couldn't have been used to crush anything."

All in all, the researchers suggest that sea scorpion pincers could have been used to entrap and slice soft-bodied and relatively weak prey.

"The impression I get was that the claws were used to grasp and manipulate food, and not the violent attacks I had assumed they were capable of," Laub said. "Instead of moving over food and tearing it up with appendages close to their mouth, they could cover a wide area without moving their bodies around much."

The arrangement of the spines and the serrations on the claws suggest "they might have been used in tandem — one would grasp food, and the other would pull them along the serrations, tearing and shredding that way, like tearing a piece of paper," he added.

Although the work suggests this group of sea scorpions might have been a gentler giant than first assumed, future research should analyze other pterygotids to see if they were indeed fierce predators. "We cannot be confident what we conclude here applies to all others as well," Laub said.

The scientists detailed their findings Dec. 20 in the Bulletin of the Buffalo Society of Natural Sciences.

- 25 Amazing Ancient Beasts

- Top 10 Beasts and Dragons: How Reality Made Myth

- Gallery: The World's Biggest Beasts

You can follow LiveScience on Twitter @livescience.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus