Woolly mammoths survived on mainland North America until 5,000 years ago, DNA reveals

Environmental reconstructions reveal that mammoths persisted long after they disappeared from the fossil record.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Woolly mammoths may have survived in North America thousands of years longer than scientists previously thought, vials of Alaskan permafrost reveal.

The hairy beasts might have persisted in what is now the Yukon, in Canada, until around 5,000 years ago — 5,000 years longer than experts previously estimated, a new study suggests. That conclusion comes from snippets of mammoth DNA that were found in vials of frozen dirt that had been stored and forgotten in a laboratory freezer for a decade.

Related: Mammoth resurrection: 11 hurdles to bringing back an ice age beast

"Organisms are constantly shedding cells throughout their life," said study lead author Tyler Murchie, a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Anthropology at McMaster University in Ontario. For instance, He explained thata person sheds roughly 40,000 skin cells per hour, on average, meaning we are constantly ejecting bits of our DNA into our surroundings.

That's also true of other life-forms; nonhuman animals, plants, fungi, and microbes are constantly leaving microscopic breadcrumb trails everywhere. Most of this genetic detritus doesn't linger in the environment, though. Soon after being discarded, the vast majority of the DNA bits are consumed by microbes, Murchie said. The fraction of the shed DNA that does remain might bind to a small bit of mineral sediment and be preserved. Though only a tiny proportion of what was initially shed remains centuries later, it can nevertheless provide a window into a vanished world teeming with strange creatures.

"In a tiny fleck of dirt," Murchie told Live Science, "is DNA from full ecosystems."

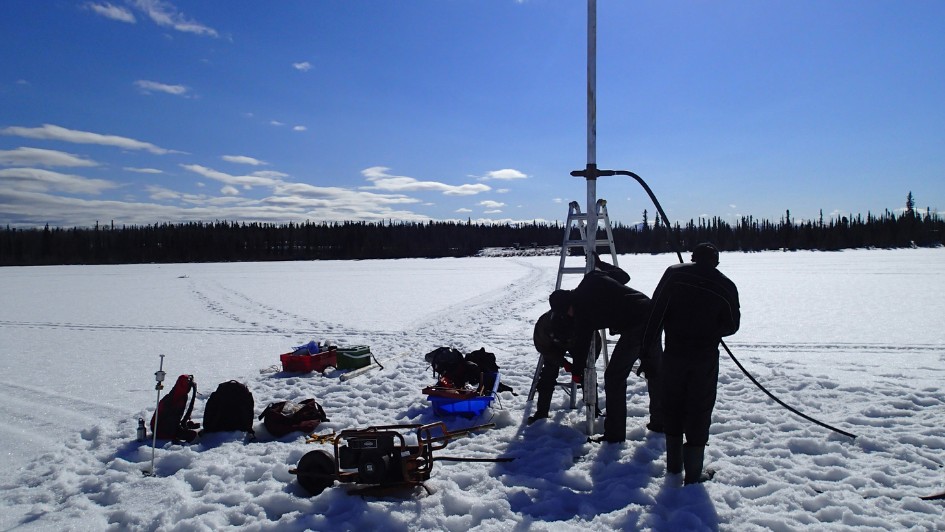

Murchie analyzed soil samples taken from permafrost in the central Yukon. Many of the samples dated to the Pleistocene-Holocene transition (14,000-11,000 years ago), a period marked by rapidly changingclimatic conditions in which many large mammals — such as saber-toothedicats, mammoths and mastodons — vanished from the fossil record.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The DNA fragments in Murchie's samples were small — often no larger than 50 letters, or base pairs. However, on average, he was able to isolate roughly 2 million DNA fragments per sample. By analyzing DNA from soil samples of known ages, he indirectly observed the evolution of ancient ecosystems over this turbulent period.

The main advantage to studying ancient DNA is that researchers can observe organisms that tended not to fossilize well. "An animal has only one body," said Murchie, and the odds of it fossilizing are not that great. On top of that, you have to find it. But that same animal constantly ejected innumerable amounts of DNA into the environment throughout its lifetime.

The soil samples — which span a period of time from 30,000 years ago to 5,000 years ago — revealed that mammoths and horses likely persisted in this Arctic environment much longer than previously thought. Mammoths and horses were in steep decline by the Pleistocene-Holocene transition, the DNA data suggest, but they didn't disappear all at once due to changes in climate or overhunting.

An earlier study, published in October in the journal Nature, suggested that some mammoths survived on isolated islands away from human contact until 4,000 years ago. However, the new study is the first to determine that small populations of mammoths coexisted with humans on the mainland of North America well into the Holocene, as recently as 5,000 years ago.

. Megafauna extinctions from this era have largely been blamed on one of two explanations: human paleo-hunters or climate catastrophe, said lead author Hendrik Poinar, an evolutionary geneticist and director of the McMaster Ancient DNA Centre.

However, the new study "changes the focus away from this two-pitted debate that has plagued [paleontology] for so long," Poinar said.

The team's research provides evidence that the extinction of North American megafauna is much more nuanced, he said. There's no doubt that the animals were under pressure from both human hunters and a rapidly changing climate. The question is, "how much were they hunted and whether or not that was truly the tipping point," Poinar told Live Science.

Analyzing ancient DNA from dirt has the potential to tell us a lot about ancient life; Poinar and Murchie said Arctic permafrost is ideal for these types of ancient DNA studies because freezing preserves ancient DNA very well. But that might not be possible forever: As ice in the Arctic melts due to rapid increases in temperature, "we're going to lose a lot of that life history data," Murchie said. "It's just going to fall away before anyone gets a chance to study it."

This study was published Dec. 8 in the journal Nature Communications.

Originally published on Live Science.

Cameron Duke is a contributing writer for Live Science who mainly covers life sciences. He also writes for New Scientist as well as MinuteEarth and Discovery's Curiosity Daily Podcast. He holds a master's degree in animal behavior from Western Carolina University and is an adjunct instructor at the University of Northern Colorado, teaching biology.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus