Viking ship in Norway buried near cult temple, feast hall and funeral mounds

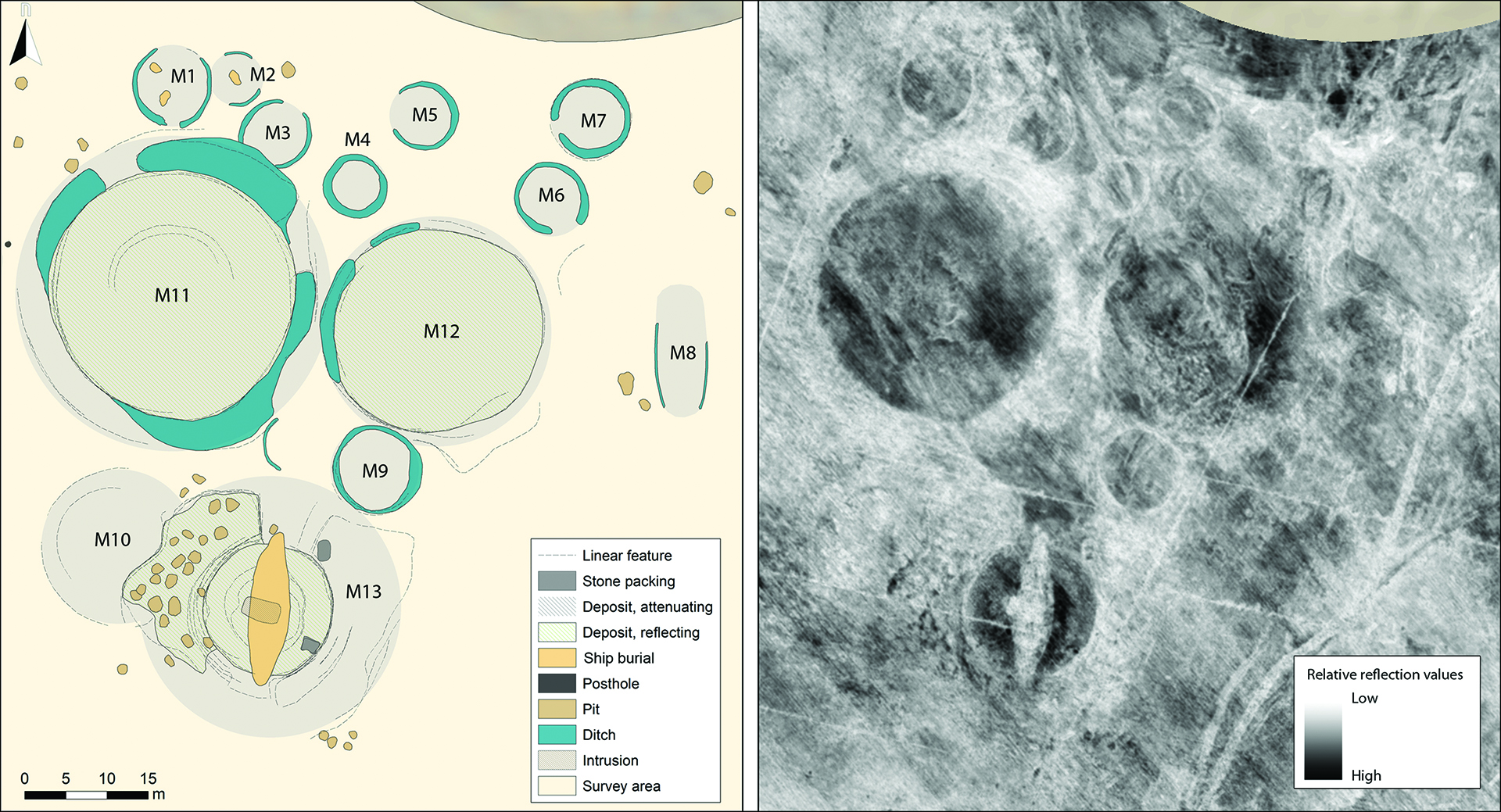

Ground penetrating radar found subterranean ritual structures.

A Viking ship that was laid to rest centuries ago wasn't alone underground. A feast hall and a cult temple were also buried at the cemetery site, hinting at the elite standing of the community that conducted the burials.

Archaeologists discovered the ship in 2018, after conducting surveys with ground-penetrating radar (GPR) at Gjellestad in southeastern Norway. Since then, further scans and excavations uncovered more clues about the site and the people who created it centuries ago.

GPR scans revealed a total of 13 burial mounds including the ship grave; some of these circular mounds were 98 feet (30 meters) wide. Other burials included buildings that may have been used in rituals, scientists reported in a new study.

Related: Photos: Vikings accessorized with tiny metal dragons

The researchers found the mound cluster to the north of a large, previously excavated Iron Age mound — Jell Mound — which dates to about 1,500 years ago (radiocarbon dating revealed that the ship was buried hundreds of years later, likely around the ninth century). Linking Jell Mound to a larger network of burials suggests that Gjellestad was an important cemetery that stood for centuries, according to the study.

In 2017, a gold ornament found near Jell Mound hinted that Gjellestad was a site of some significance. Pendants such as these were often included in burials of high-status women during the Iron Age, around A.D. 1 to A.D. 400, according to the study.

Numerous funerary mounds once studded the landscape around Gjellestad, but many of these were plowed up by farmers during the 19th century, the scientists wrote. However, even after a mound has been destroyed, GPR can still reveal its former location — and what was buried there.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Near the ship grave, GPR located two large circular mounds, with seven smaller mounds clustered to the north. Four rectangular "settlement structures" lay to the west; the longest was 125 feet (38 m) in length. One of the smaller buildings may have been a farmhouse; another may represent a temple; and the largest building was similar in structure and size to feasting halls found in other Viking settlements, the scientists reported.

"The only structure that can be securely dated to the Viking Age at Gjellestad is the ship burial but, taking the whole site into consideration, we can probably say that it was important for the elite to exhibit their status through lavish and carefully planned burial rituals," said lead study author Lars Gustavsen, an archaeologist with the Norwegian Institute for Cultural Heritage Research (NIKU).

"We believe that the inclusion of a ship burial in what was probably an already existing — and long-lived — mound cemetery was an effort to associate oneself with an already existing power structure," Gustavsen told Live Science in an email.

A grave situation

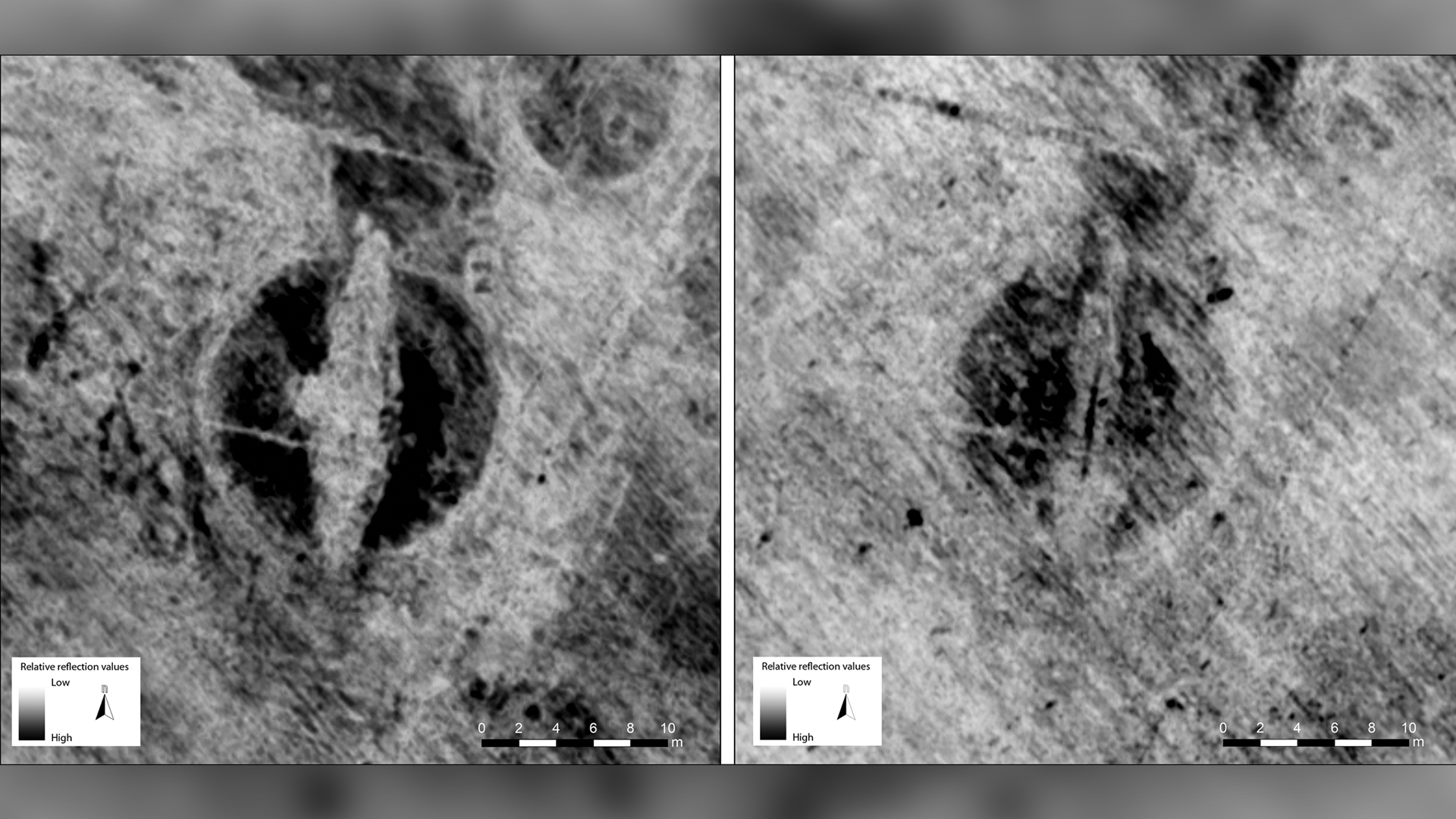

The ship burial itself was highly unusual. Viking burials of boats measuring under 39 feet (12 m) are common, but finding a ship this large — 66 feet (20 m) in length — is exceptionally rare. In fact, only a handful of such burials are known across Norway, Gustavsen said.

The last excavations of large Viking ships took place more than a century ago, during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. This is the first such ship to be found through GPR-scanning technology, which bodes well for discovering more ship burials that are still hidden, according to the study.

But why did Vikings bury their ships? "We do not really know for certain," Gustavsen said. "Since these were societies whose identity was closely tied to the sea and seafaring, the ship could, in this specific context, be seen as a vessel transporting the dead from the realm of the living to the realm of the dead," he said.

"Or it could simply be a display of wealth, or to demonstrate that one belonged to a certain social and political class."

After the ship's discovery in 2018, the team partially excavated the ship and quickly realized that damp conditions combined with periods of drought had left the ship badly decomposed and riddled with fungus, Live Science previously reported.

Over the summer of 2020, archaeologists mounted a full excavation to recover and preserve what they could of the decaying ship. In October, the team found something unexpected: animal bones, according to a statement published by the University of Oslo's Museum of Cultural History.

"The animal bones are relatively large in size, so we think that they are the remains of an ox or a horse that has been sacrificed to be part of the burial," museum representatives said in the statement. "Although the topmost layers of the bones are heavily decomposed, they seem to be better preserved further down. This indicates that it is quite likely that things are better preserved deeper into the ship burial."

Work on the site is still underway, and is expected to be completed in December, according to Gustavsen.

The findings were published online Tuesday (Nov. 11) in the journal Antiquity.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus