Adorable, bug-size sunfish babies grow up to be giant 'swimming heads'

Sunfish in the Molidae family are among the biggest fish in the world.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

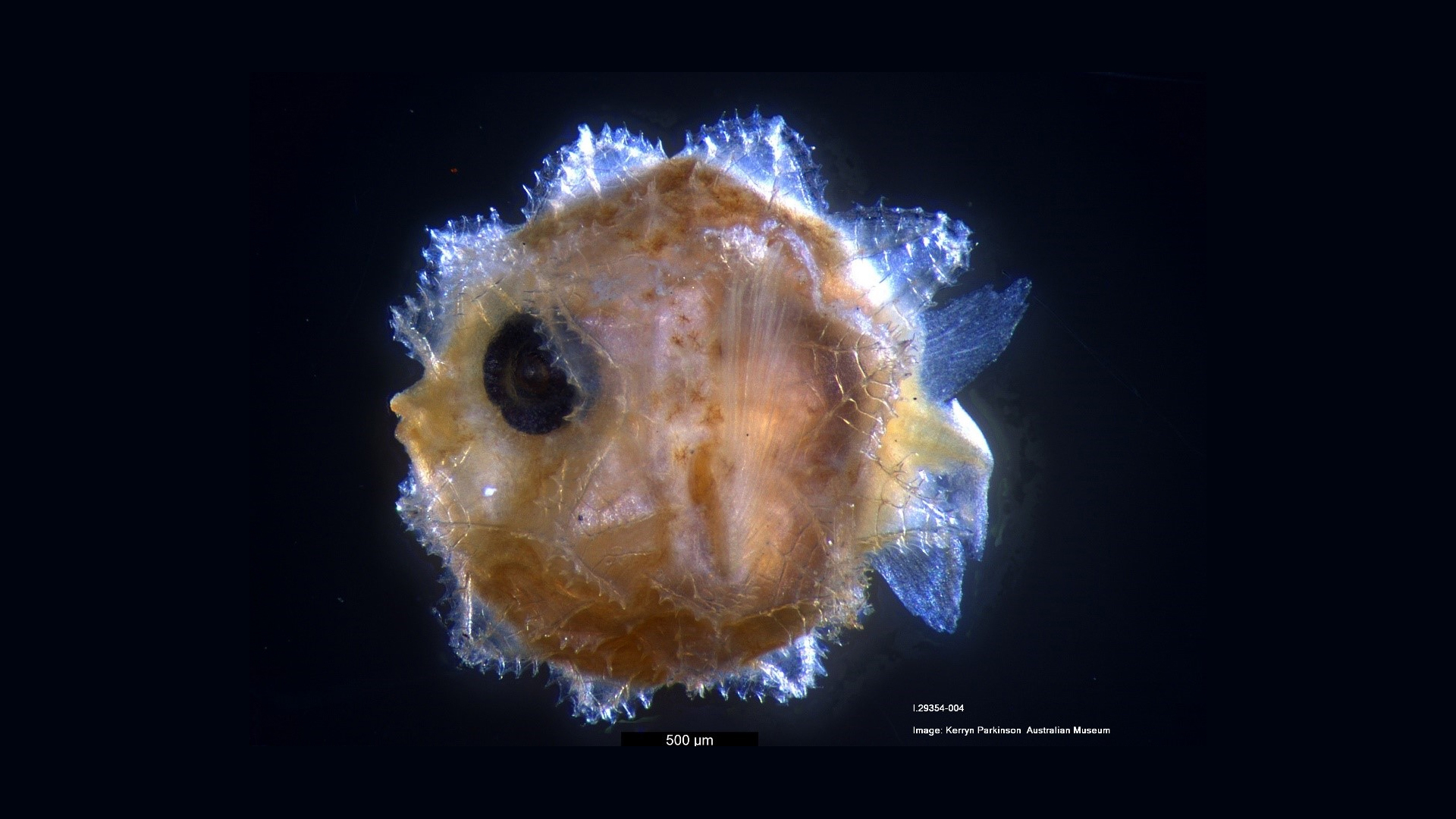

Scientists have identified the babies of one of the world's biggest fishes — the mola, or sunfish — and the youngster is so small that you could easily fit a dozen of them on your fingertip.

Adult sunfish are the heaviest bony fish in the world, measuring up to 10 feet (3 meters) long and weighing more than 4,400 lbs. (2,000 kilograms). They are also bizarrely shaped; adults resemble enormous, flattened pancakes topped by a massive dorsal fin like a shark's. Their bodies are unusually short and have no tail fin, as most fish do. Instead, sunfish have a long structure at their rear end known as a clavus, which extends downward and resembles a boat's rudder.

But mola babies are a different story. As larvae, they measure just a few millimeters in length and their bodies look nothing like those of adults. Because of that, scientists struggle to match larvae with the correct species of mola. But for the first time, DNA sequencing identified the larvae of the bump-head sunfish (Mola alexandrini), representatives of the Australian Museum said in a statement.

Related: In photos: The world's largest bony fish

There are six sunfish species in the family Molidae; they are found in oceans throughout the world and have many whimsical names reflecting their peculiar shape. Sunfish are also known as "poisson lune" (French for "moon fish"); "klumpfisk" (Danish for "lumpfish"); and "schwimmender kopf" (German for "swimming head"), according to FishBase, a global online database of fish species.

Because sunfish larvae are so tiny, they are extremely difficult to find, let alone identify. But in 2017, researchers working off the coast of New South Wales in southeastern Australia managed to collect tiny sunfish larva measuring about 0.2 inches (5 mm) long. By carefully removing one of a larva's eyeballs for genetic sequencing, the scientists were able to minimize damage to the precious specimen and extract usable DNA, according to the statement. They compared the DNA to genetic samples collected from adult sunfish, and found a match to M. alexandrini.

Having identified this wee baby — a youngster that is about 600 times smaller than a full-grown sunfish — scientists can now compare the larva to unidentified Mola larvae in the collections of the Australian Museum and the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation in Hobart, Australia to see if there are more matches, said Marianne Nyegaard, a research associate at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and one of the scientists who analyzed the tiny fish.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

In addition to the bump-head sunfish, four more species of sunfish live in waters around Australia: the oceanic sunfish (Mola mola), the hoodwinker sunfish (Mola tecta), the point-tailed sunfish (Masturus lanceolatus) and the slender sunfish (Ranzania laevis). Further research into sunfishes' bug-size babies will help scientists piece together clues about early life for this group of unusual fish, Nyegaard said in the statement.

"If we want to protect these marine giants we need to understand their whole life history, and that includes knowing what the larvae look like and where they occur," Nyegaard said.

Originally published on Live Science.

Mindy Weisberger is a science journalist and author of "Rise of the Zombie Bugs: The Surprising Science of Parasitic Mind-Control" (Hopkins Press). She formerly edited for Scholastic and was a channel editor and senior writer for Live Science. She has reported on general science, covering climate change, paleontology, biology and space. Mindy studied film at Columbia University; prior to LS, she produced, wrote and directed media for the American Museum of Natural History in NYC. Her videos about dinosaurs, astrophysics, biodiversity and evolution appear in museums and science centers worldwide, earning awards such as the CINE Golden Eagle and the Communicator Award of Excellence. Her writing has also appeared in Scientific American, The Washington Post, How It Works Magazine and CNN.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus