The Taliban may be hunting for Afghanistan's most famous treasure

The Bactrian treasure holds 20,000 golden artifacts.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

With the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan, the country's archaeological remains face a grim future even if the extremist Islamic group decides not to loot or intentionally destroy them.

Some news reports suggest the Taliban are already hunting for one of the country's most famous caches; the so-called "Bactrian Treasure" is a collection of more than 20,000 artifacts, many made of gold, that were found in 2,000-year-old graves at a site called Tillya Tepe in 1978. The treasure was kept in the National Museum of Afghanistan and was on display at the presidential palace, but reports indicate that its present location is unknown.

Other archaeological remains that could be threatened by the Taliban include Mes Aynak, a Buddhist city that flourished around 1,600 years ago. The city was located along the iconic Silk Road and was used for both trade and worship; numerous ancient Buddhist monasteries and other ancient Buddhist artifacts are buried there.

Related: Photos: Ancient Buddhist monastery in Mes Aynak

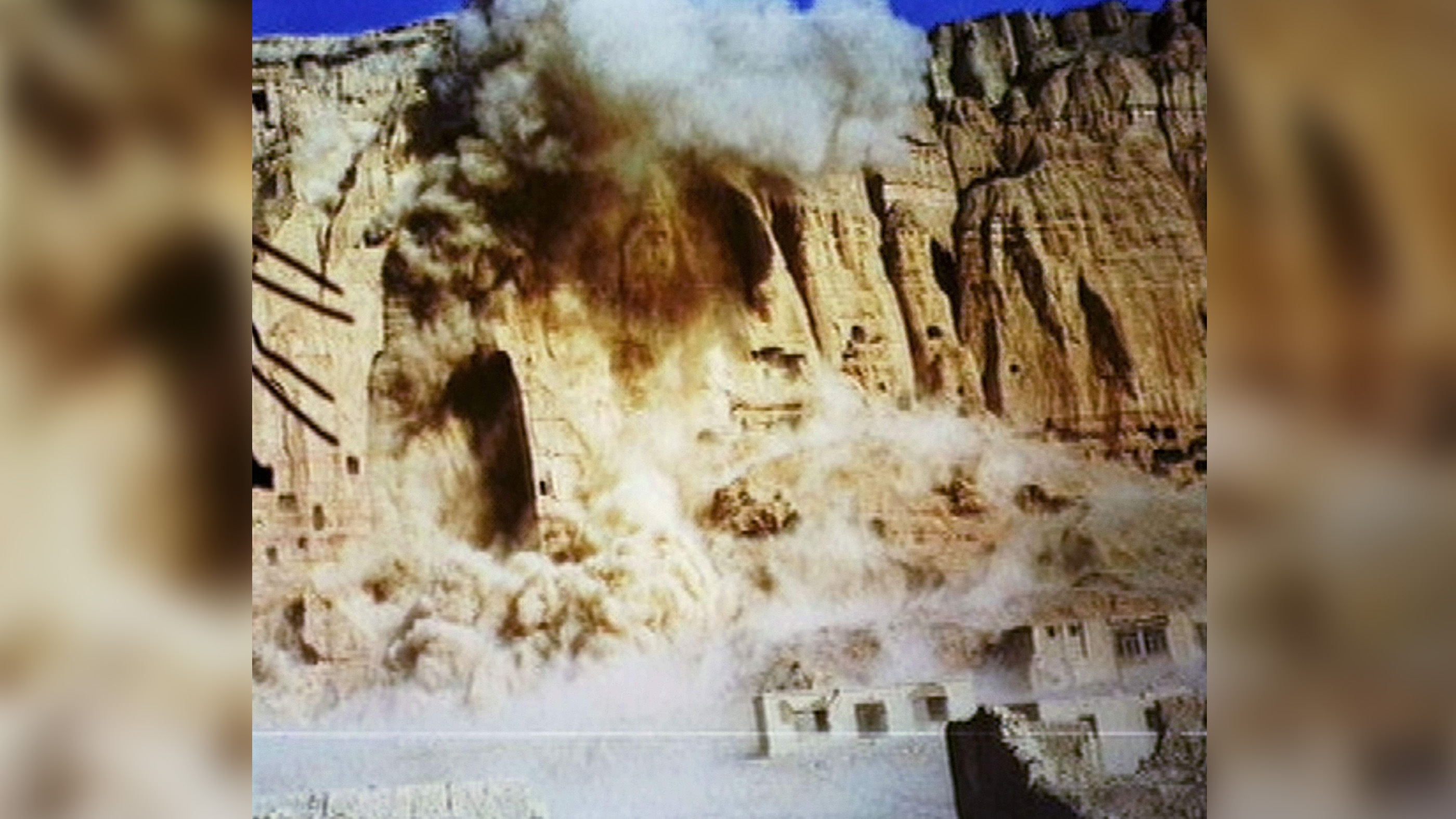

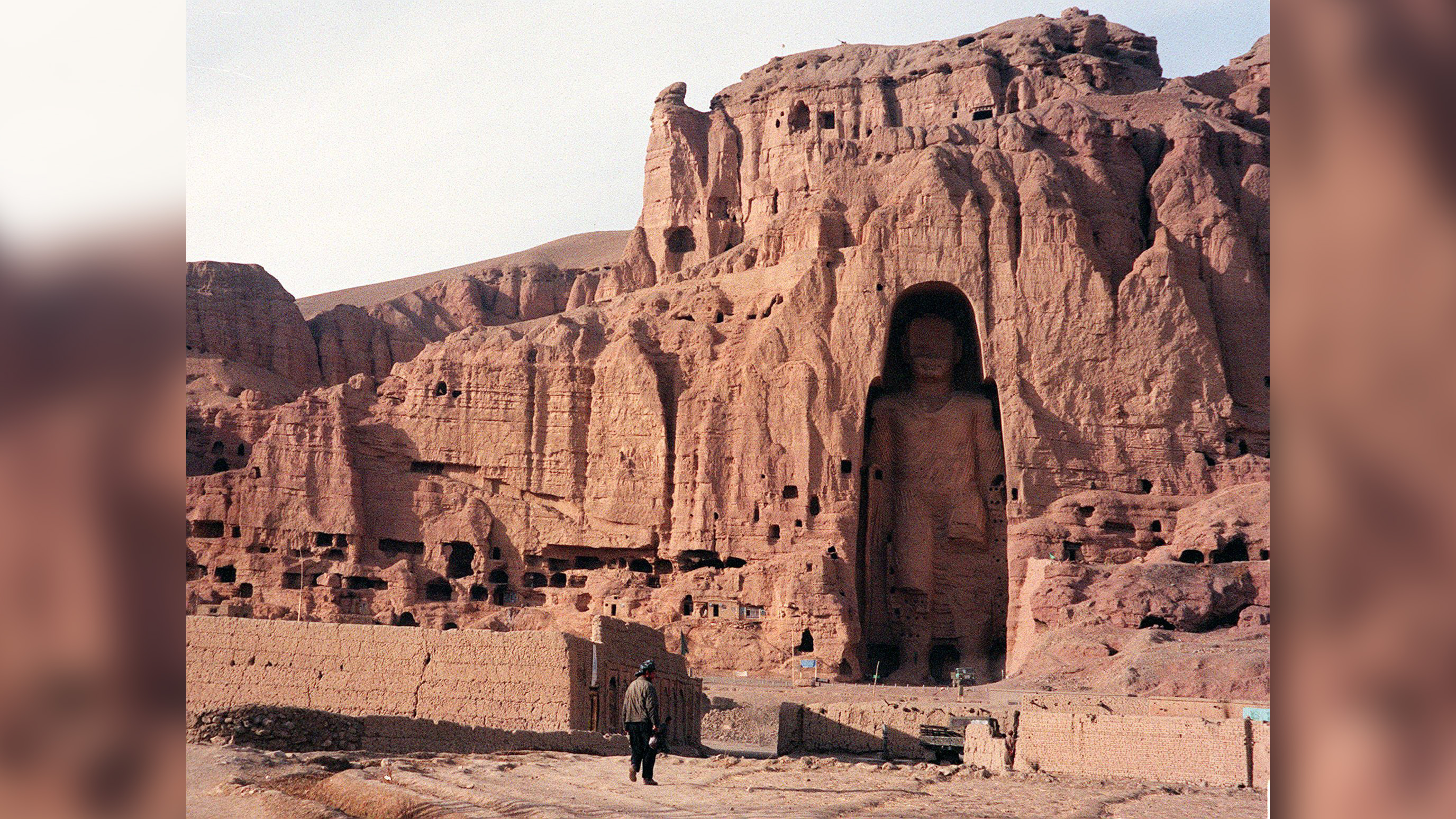

When the Taliban ruled Afghanistan between 1996 and 2001, they destroyed many of these Buddhist artifacts, including two massive sixth-century statues known as the "Buddhas of Bamiyan "that were carved into a cliff there. The extremist group used rockets, tank-fired projectiles and dynamite to take down the towering statues, according to news reports.

The future of Mes Aynak looks particularly bleak as sources told Live Science that all the equipment used for excavation and conservation at the site is gone; and the Taliban have been visiting the site for unknown purposes.

"The situation for culture heritage is not OK, because right now no one is taking care of the sites and monuments," said Khair Muhammad Khairzada, an archaeologist who led excavations at Mes Aynak. "All archaeological sites in Afghanistan are [at] risk," said Khairzada, noting that there is "no monitoring, no treatment and no care, all departments in all province [are] closed, without money and other facilities" that are needed to "take care [of] the sites and monuments." Recently, Khairzada was forced to flee to France to escape the Taliban.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Khairzada said that all the equipment that they had used for excavation and conservation at Mes Aynak is "gone." China holds mining rights in the nearby areas and even before the Taliban took over archaeologists feared that parts of the site could be destroyed if it were turned into a mine. After the Taliban took over Kabul they announced that they would seek economic support from China, but it is unclear if China intends to build a mine in the area.

Related: $1 trillion trove of rare minerals revealed under Afghanistan

Julio Bendezu-Sarmiento, who was director of the French Archaeological Delegation to Afghanistan, said that he has learned that the Taliban have visited Mes Aynak but is uncertain why. "It is difficult to say what the immediate objectives of this visit are," Bendezu-Sarmiento said. There had been plans to hold an exhibition of artifacts from Mes Aynak and other Afghanistan sites in France in 2022, but the Taliban captured Kabul before artifacts could be transported.

So far there have been no reports of the Taliban intentionally destroying artifacts, and the Taliban leadership has issued statements saying that they will protect archaeological sites; however, whether the Taliban will actually follow through on their promises is unknown.

Satellite imagery

Along with his team, Gil Stein, a professor at the University of Chicago's Oriental Institute who leads the Afghan Heritage Mapping Partnership, has been using satellite imagery to map and monitor thousands of archaeological sites in Afghanistan. Stein estimates that they have mapped out the location of about 25,000 archaeological sites in Afghanistan so far. Looting is a long-running problem in Afghanistan, but Stein said that so far he has found no evidence that the Taliban have been supporting it.

While the Taliban took control of Kabul and parts of northern Afghanistan recently, they have been in control of parts of southern Afghanistan for several years. Areas in the south that the Taliban have controlled for years don't have the large-scale looting that was seen in territories controlled by the Islamic State group (ISIS or ISIL) in Syria and Iraq, Stein told Live Science.

"Basically, the Taliban were not sponsoring looting as a source of income the way [ISIL] was doing," Stein said. However, the team has found many cases in southern Afghanistan where agricultural fields, which often grow opium, were built over archaeological sites. The Taliban "didn't need to sponsor looting because they have been making such an enormous amount of money from the opium trade," Stein said.

The northern areas of Afghanistan, which the Taliban has only recently taken over, hold far more archaeological sites than the southern areas. After examining recent satellite imagery of northern Afghanistan, Stein's team saw "battle-related damage" but not new cases of wide-scale looting.

Only time will tell if the Taliban will refrain from looting or destroying archaeological sites, he said. In one encouraging event, the Taliban posted guards outside the National Museum of Afghanistan, said Stein, noting that during the 2003 U.S. invasion of Iraq there were no guards posted outside the Baghdad Museum where looting took place during the chaos.

Even if the Taliban leadership in Kabul has decided to protect archaeological remains, there is no guarantee that Taliban groups in other parts of Afghanistan will follow those orders, Stein said.

In addition, many heritage professionals who are still in Afghanistan are afraid for their lives. "I know that the people engaged in heritage preservation are very, very, worried because nobody knows what's going to happen, and if you go by what the Taliban did in the past you would have really good reason to be extremely scared [for both their lives and Afghanistan's heritage]."

It is perilous for heritage professionals in the country to keep in touch with people outside of Afghanistan, Stein said; he has heard cases of Taliban stopping people in the streets and searching their cellphones to see if there are any foreigners in their contacts. In August the Taliban killed an Afghan folk singer but so far there are no recent reports of the Taliban killing archaeologists. Some heritage professionals had hoped to leave Afghanistan, Stein said, but they were not able to get out before the Americans withdrew from Kabul's airport at the end of August.

Over the last two decades, some artifacts that were looted or stolen from Afghanistan were found in the United States and repatriated to Afghanistan. As far as Stein knows, artifacts that were repatriated are still in the National Museum of Afghanistan, he said.

Live Science contacted U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement [ICE] to ask what their policy would be in future cases where stolen Afghanistan artifacts are found in the United States. They did not reply by the time of publication.

Originally published on Live Science.

Owen Jarus is a regular contributor to Live Science who writes about archaeology and humans' past. He has also written for The Independent (UK), The Canadian Press (CP) and The Associated Press (AP), among others. Owen has a bachelor of arts degree from the University of Toronto and a journalism degree from Ryerson University.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus