Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Running out of gas is annoying at the best of times, let alone if you're a satellite traveling at speeds of up to 17,500 mph (28,200 km/h) high above Earth's surface. At the moment, a satellite that burns through all its fuel simply becomes space junk, adding to the vast debris field surrounding our planet.

"It's the equivalent of buying a car with one tank of fuel in it, and you throw the car away when you run out of that fuel," Ray Fielding, head of space sustainability at the UK Space Agency, told Live Science. Often, the satellites are perfectly functional and just lack the fuel to maneuver around debris, he added.

However, the space industry is aiming to change this paradigm by investing in projects that will allow satellites to be refueled and serviced in orbit. In addition to mitigating the growing problem of space junk, this more sustainable approach could cut down on wasted resources and reduce the costs associated with operating satellites.

Related: Undiscovered 'minimoons' may orbit Earth. Could they help us become an interplanetary species?

Reviving the orbital 'dead'

Colorado-based startup Orbit Fab aims to provide an all-inclusive satellite refueling service by 2025. The company also plans to offer repositioning services, potentially allowing for both longer and more versatile satellite operations. In fact, fuel is already available for preorder. It costs $20 million for 100 kilograms (220 pounds) of hydrazine, a common rocket fuel.

To accomplish this, Orbit Fab proposes a network of fuel depots parked in orbit and a fleet of fuel shuttles to dock with and refuel client satellites. Key to the vision is the company's refueling interface, the Rapid Attachable Fluid Transfer Interface (RAFTI). By replacing the conventional fill and drain valves found on satellites, RAFTI provides a universal way to refuel satellites on the ground or in orbit.

Recognizing the importance of an international standard for refueling interfaces, Orbit Fab released the designs for RAFTI under an open license in 2021, meaning anyone can produce it. The design has already been incorporated into more than 100 commercial satellites, according to Orbit Fab. However, a vast majority of satellites in orbit are not compatible.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Fielding likened this situation to cellphone chargers, suggesting we could end up with a bewildering array of incompatible solutions. The UK Space Agency is investigating a range of interfaces, including RAFTI, to find the best solution and plans to share the findings with the international community to encourage the adoption of an international standard.

"The last thing I want to do in orbit is have the wrong connector and be unable to provide the service," Fielding said.

The results of the testing will also inform the space agency's choice of interface for an upcoming debris-removal mission, which will incorporate refueling technology. Working with industry partners such as ClearSpace and Astroscale and anticipated to launch in 2026, the mission aims to remove at least four derelict satellites from orbit by pushing them into the lower atmosphere with a robotic arm.

NASA's on the case

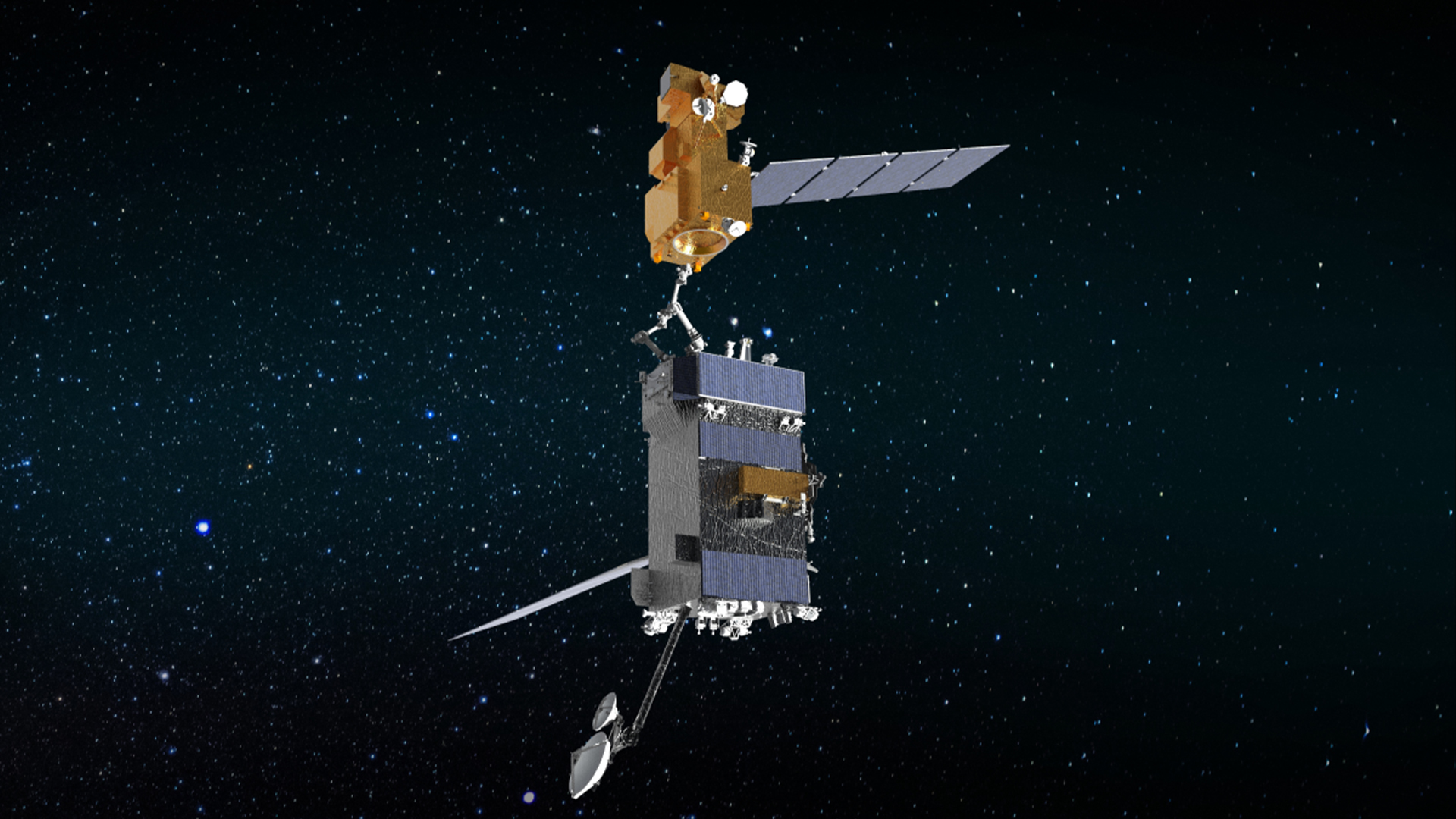

Meanwhile, NASA is also developing technology to make satellite refueling a reality through the ongoing On-orbit Servicing, Assembly, and Manufacturing 1 (OSAM-1) mission.

OSAM-1 is a craft designed to refuel satellites in space. Notably, these satellites include those that weren't designed to be refueled — something Orbit Fab doesn't plan to do. OSAM-1, which is part of NASA's Technology Demonstration Missions program, was planned to launch in 2026 but is reportedly delayed and over budget.

NASA plans to demonstrate OSAM-1's capabilities by refueling Landsat 7, an Earth-observing satellite launched in 1999. The mission hopes to showcase a suite of new technology, including advanced systems to enable reliable autonomous docking of OSAM-1 to other craft.

"The last thing you want is any sort of collision in any way, shape or form between the two objects," Fielding said. "So sensors, the recognition aspects, the ability to understand and then complete the interfaces needed autonomously are going to be crucial."

Ivan is a freelance science writer based in the UK. He enjoys covering a variety of topics within science, and holds a PhD in medicinal chemistry.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus