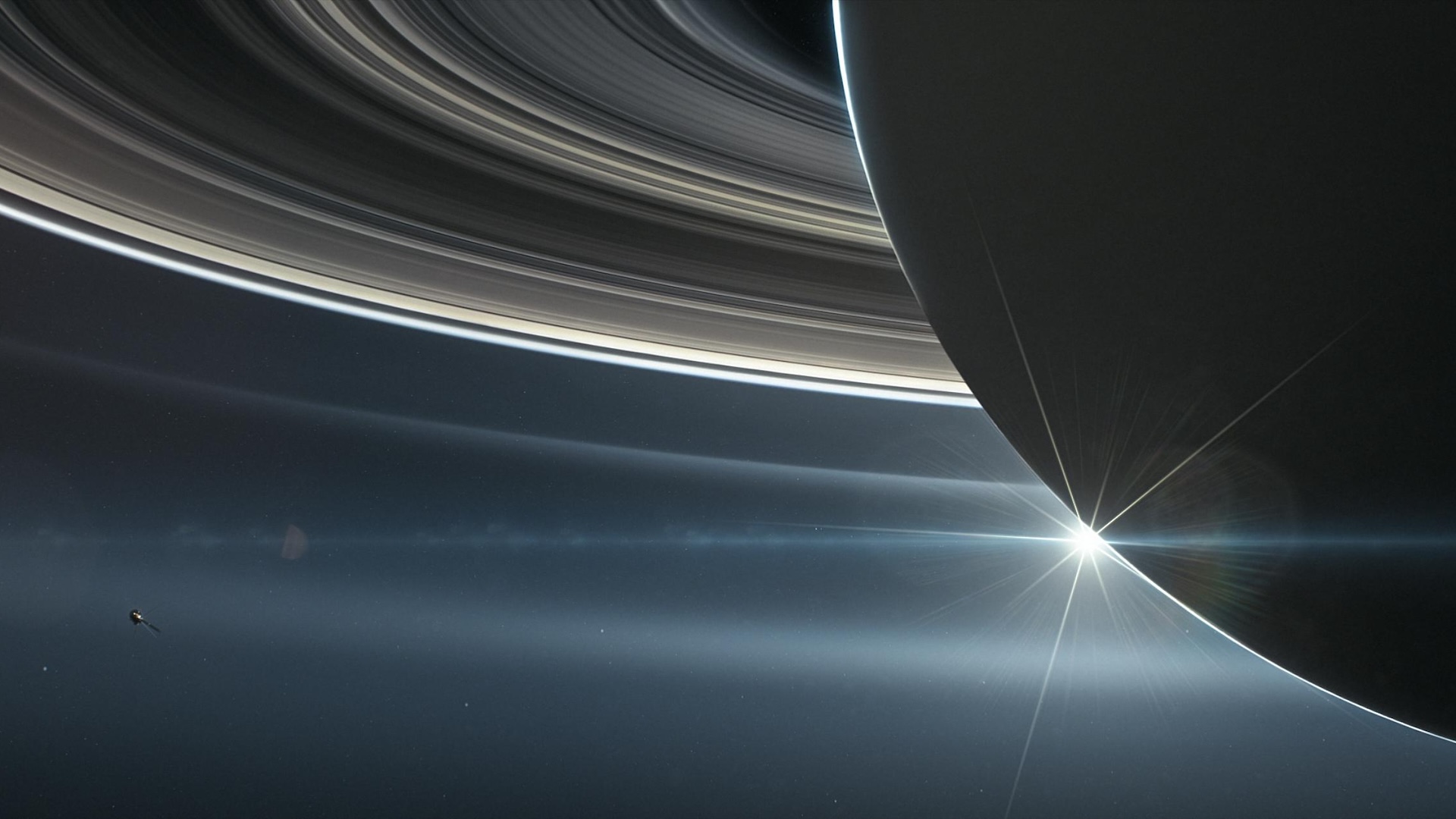

Saturn gains 128 new moons, giving it more than the rest of the solar system combined

Faint signatures detected by the Canada France Hawaii Telescope have revealed 128 new moons around Saturn, making it the indisputable frontrunner for having the most moons in our solar system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

Astronomers have discovered 128 never-before-seen moons orbiting Saturn — giving it almost twice as many moons as all the other planets in the solar system combined.

The findings have further bolstered Saturn's status as our solar system's "moon king." With an updated total of 274 known natural satellites orbiting the gas giant, it is leagues ahead of its main competitor Jupiter, which has just 95 confirmed moons.

This week, the International Astronomical Union officially recognized the team's discovery. The researchers published their findings March 10 in the journal arXiv, so they have not yet been peer-reviewed.

"Our carefully planned multi-year campaign has yielded a bonanza of new moons that tell us about the evolution of Saturn's irregular natural satellite population," study lead author Edward Ashton, an astronomer at Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics at Academia Sinica, Taiwan, said in a statement.

The newfound moons are situated within the Norse group of Saturn's moons — a group of moons that orbit in retrograde (travelling in the opposite direction to the planet’s rotation) along elliptical paths outside Saturn's rings. The 128 newly discovered objects are considered "irregular" moons, meaning they're only a mile or two in size and far from spherical.

Related: NASA finds key ingredient for life gushing out of Saturn's icy moon Enceladus

Their diminutive sizes and location means these moons are likely fragments of larger moons that were smashed apart by a cataclysmic collision — probably with Saturn's other moons or a passing comet. This collision could have occurred as recently as 100 million years ago, the astronomers said in the study.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The discovery was made using the Canada France Hawaii Telescope (CFHT), which combed the sky around Saturn between 2019 to 2021 and discovered an initial 62 additional moons in its orbit. The team also found faint signals of an even larger number of orbiting bodies but were unable to confirm them at the time.

"With the knowledge that these were probably moons, and that there were likely even more waiting to be discovered, we revisited the same sky fields for three consecutive months in 2023," Ashton said. "Sure enough, we found 128 new moons. Based on our projections, I don't think Jupiter will ever catch up."

The researchers say they are now finished moon-spotting for the foreseeable future, at least until telescopes capable of spotting even fainter signatures are developed.

"With current technology I don't think we can do much better than what has already been done for moons around Saturn, Uranus and Neptune," Ashton said.

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus