Russia's Ukraine invasion could imperil international science

Unfortunately, the scientific community could face ramifications due to the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has forced at least 1 million people to flee their homes, and has already seen thousands of Ukrainian civilians killed, could also have wide-reaching and prolonged ramifications for scores of industries and organizations, including many designed to be apolitical.

Global efforts that could suffer include international science collaborations, which focus predominantly on the pursuit of technological and scientific progress. They do this by harnessing knowledge from all corners of the globe: The intention is to create positive change through collaborative effort, and generally operate without political interference.

The unfolding crisis in Ukraine, however, has raised many questions about such partnerships. Should Russia continue to play a role in global projects? Will sanctions stretch to include scientific endeavors? And should international organizations focused on collaboration make a point of remaining politically agnostic?

Various scientific projects around the world — and a notable one beyond Earth's atmosphere — involve Russia, so let's take a look at how these collaborations have reacted to Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

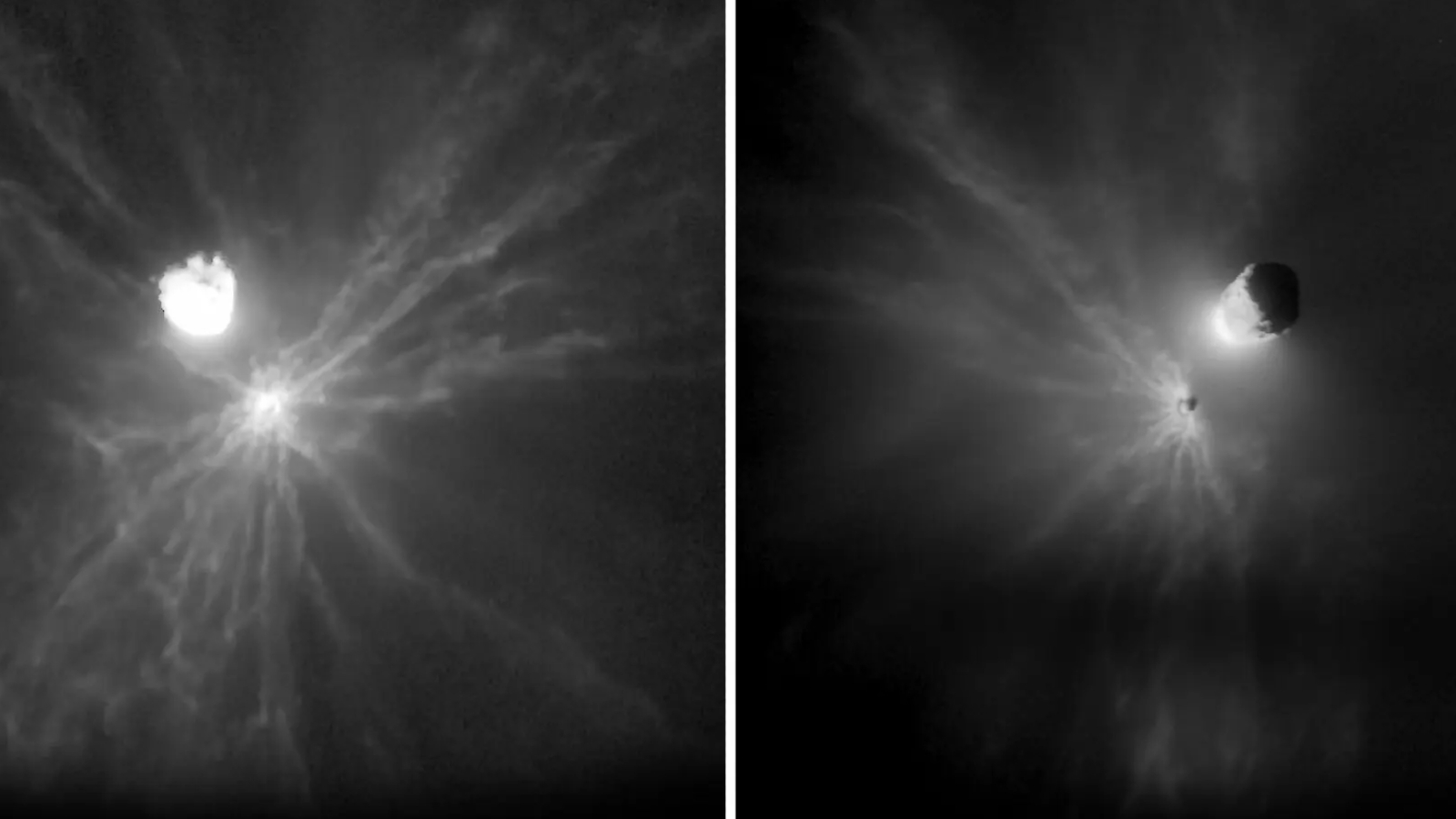

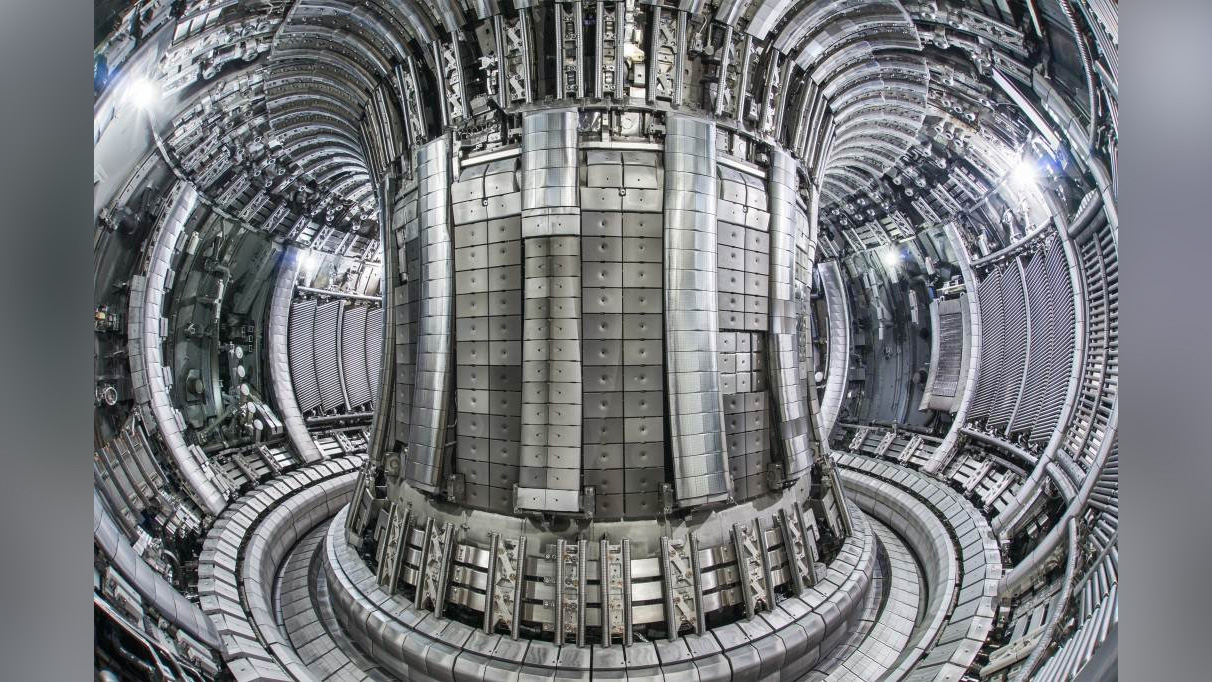

ITER

ITER is the world's largest fusion experiment. It involves 35 nations — including Russia, the United States and China — and since its inception, has focused on replicating the sun's fusion processes in a bid to create clean, almost limitless energy on Earth.

To date, Russia's invasion of Ukraine has not resulted in any notable changes to the organization's work. "To my knowledge, there have been no impacts so far," ITER spokesperson Laban Coblentz told Live Science.

ITER was launched as an international project during the Cold War. It has always been collaborative, not because its members are ideologically alike, but "because they share a common goal for a better future," Coblentz said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"Throughout ITER's history, political differences among its members — trade wars, border disputes and other disagreements — have never affected the collaborative spirit," Coblentz added. "It is a project of peace."

However, Coblentz was keen to highlight that though the project has not previously been disrupted by political strife, "the events of recent days are without precedent, so we don't know what the effect will be. It is too early to draw conclusions," he said.

He hopes all ITER members will remain "committed to collaboration" and will ultimately be able to focus on their potentially world-changing work.

The European Space Agency

The European Space Agency (ESA) was quick to condemn Russia in the wake of the Ukrainian invasion. In an official statement released Feb. 28, it highlighted the "tragic consequences of the war in Ukraine" and declared that it would give "absolute priority to taking proper decisions, not only for the sake of our workforce involved in the programmes, but in full respect of our European values."

Consequently, ESA stated it would be "fully implementing sanctions imposed on Russia by our Member States." As such, the agency admitted that the ExoMars program — a collaboration with Roscosmos (Russia's space agency) to look for signs of past life on Mars — will likely be delayed. "Sanctions and wider context make a launch in 2022 very unlikely," ESA said, adding that it will continue to monitor the situation "in close contact with its Member States."

The International Science Council

The International Science Council (ISC), a non-governmental organization dedicated to uniting scientific bodies with the aim of advancing science as a "global public good," also issued a swift rebuke following Russia's incursion into Ukrainian territory.

An official statement notes the ISC's "deep dismay and concerns regarding the military offensives being carried out" and suggests "the conflict in Ukraine and its consequences will hamper the power of science to solve problems when we should be harnessing it."

However, the ISC's statement also confirmed that the council will not be cutting ties with Russia. "The isolation and exclusion of important scientific communities is detrimental to all," the ISC said, adding that "to work collaboratively on global challenges, and on cutting edge research such as Arctic and space research, is only equal to our capacity to maintain strong collaboration amidst geopolitical turmoil."

The ISC "is committed to advancing the equal participation and collaboration between scientists in all countries in its activities and the principle of the free and responsible practice of science."

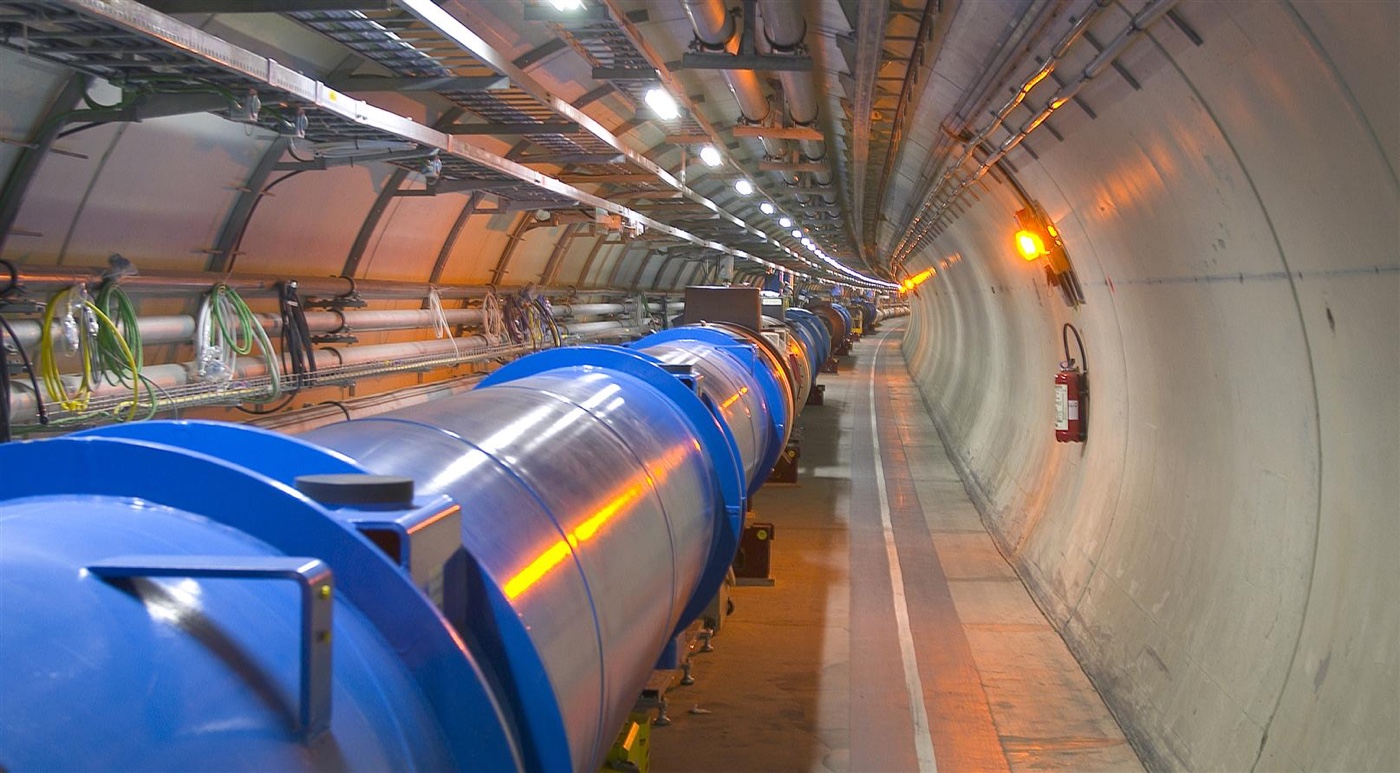

CERN

CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research — home to the world's largest atom smasher, the Large Hadron Collider — has yet to release an official statement regarding the conflict in Ukraine. A CERN spokesperson told Live Science they were "unfortunately not able to reply to questions regarding how Russia's invasion of Ukraine will impact international science/technology projects."

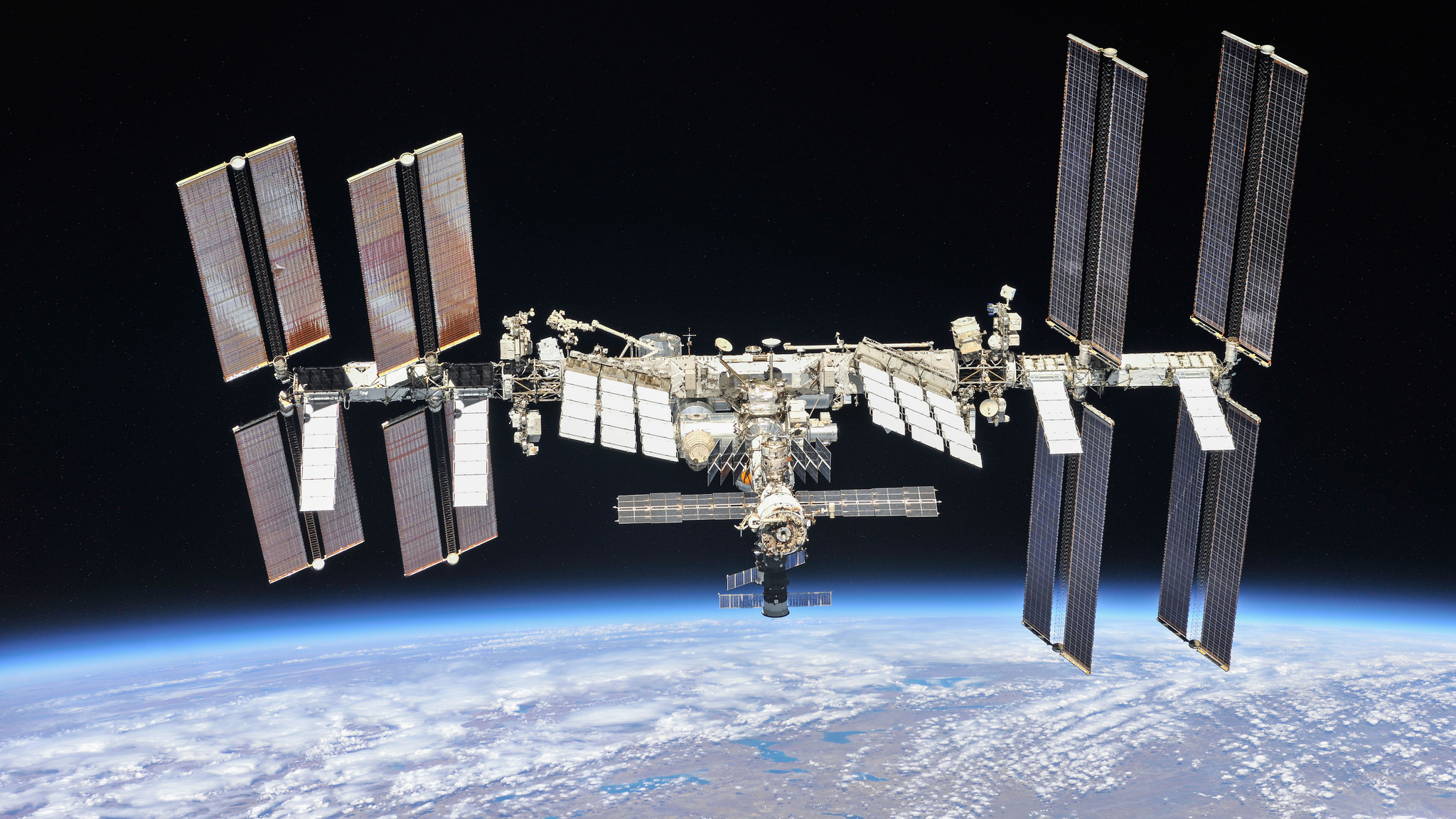

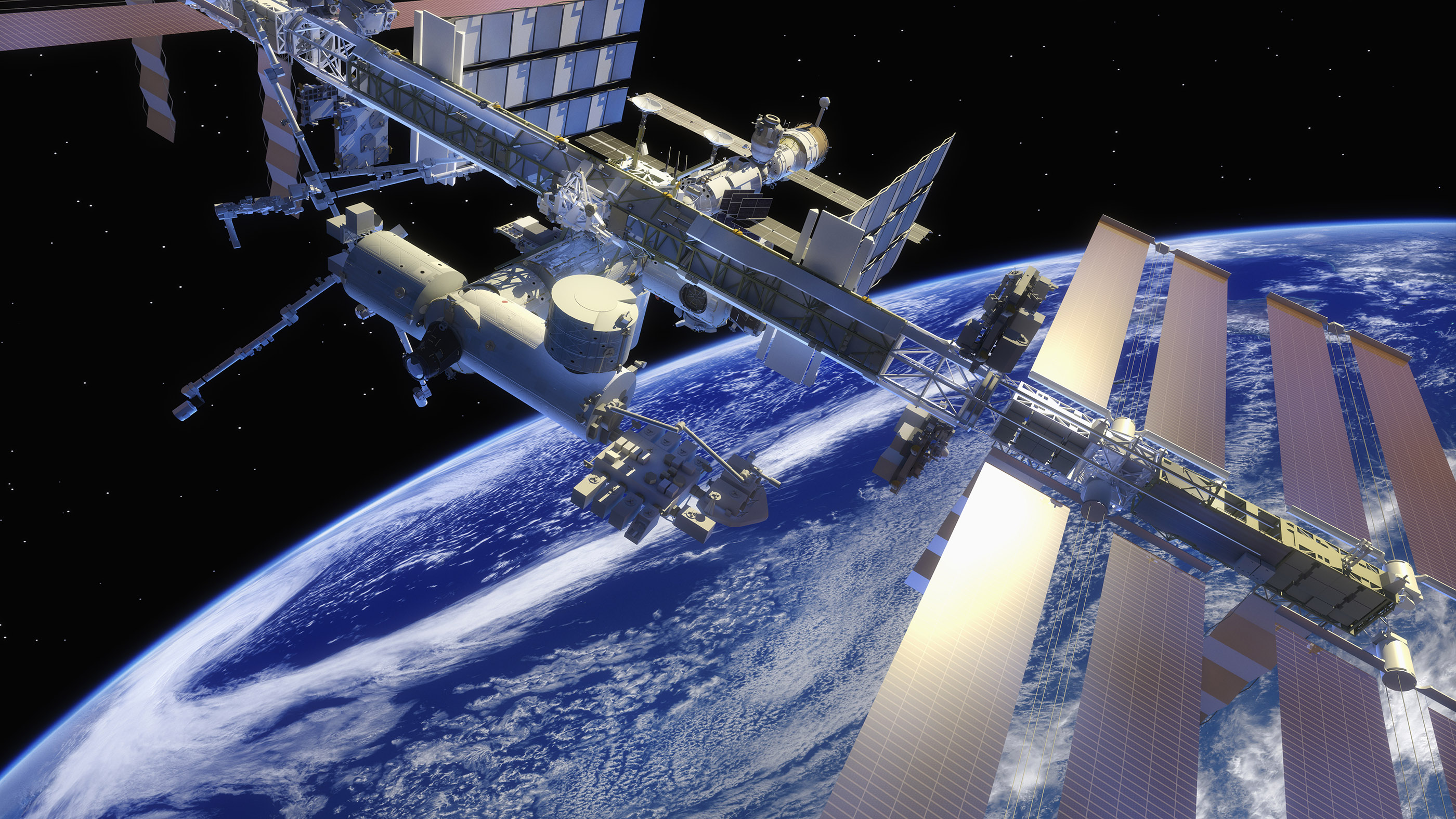

International Space Station

The International Space Station (ISS) has long been lauded for showcasing the value of collaboration and cross-border cooperation. Five space agencies participate in the orbiting space lab: NASA, Roscosmos, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, ESA and the Canadian Space Agency. Since its construction began in 1998, the ISS has conducted scientific research and carried out a host of valuable, nation-agnostic experiments.

The ongoing crisis in Ukraine, however, has created ripples.

Taking to Twitter on March 3, Roscosmos declared that it had canceled joint scientific experiments due to be conducted on the ISS in collaboration with Germany — a statement that arrived just days after Russia signaled that it may not continue to help operate the ISS. This could result in the station having to be decommissioned before its scheduled end date of 2031.

⚡ Госкорпорация не будет сотрудничать с Германией по совместным экспериментам на российском сегменте МКС. Роскосмос проведет их самостоятельно.⚡ Российская космическая программа на фоне санкций будет скорректирована, приоритетом станет создание спутников в интересах обороны. https://t.co/zl7CRNstGGMarch 3, 2022

The current crew of seven aboard the ISS consists of Russians Anton Shkaplerov and Pyotr Dubrov, Americans Kayla Barron, Mark T. Vande Hei, Raja Chari and Thomas Marshburn, and a solitary German, Matthias Maurer.

Speaking on Feb. 28, Kathy Lueders, Associate Administrator of the Space Operations Mission Directorate and NASA's most prominent official on human spaceflight, said: "We understand the global situation, but as a joint team, these teams are operating together." She added: "We are not getting any indications at a working level that our counterparts are not committed to ongoing operation of the International Space Station," according to Space.com.

However, it's clear that, on Earth, there is tension, and the situation is changing daily.

On March 3, Dmitry Rogozin, Director General of Roscosmos, said that Russia will stop — for the time being at least — its space cooperation with the United States. He said Russia will no longer deliver rocket engines to the U.S., nor will it provide maintenance, and suggested America instead uses “broomsticks” to power themselves into space.

However, Tony Bruno, CEO of United Launch Alliance, an American spacecraft launch service provider, has suggested that Russia’s actions may not have a significant immediate impact. "We like to be able to consult with them [Russia] in the event that the engine might do something unexpected," he said via his Twitter account. "But, we have been flying them for years and have developed considerable experience and expertise," he added.

The uncertainty around Russia's continued dedication to the ISS project encouraged billionaire Elon Musk to take to Twitter to suggest that, should Russia stop contributing, his company, SpaceX, will be capable of filling the void and can keep the ISS operational.

Musk was responding to a series of tweets posted by Rogozin in which the Russian asked “who will save the ISS from an uncontrolled deorbit into the United States or Europe,” before ominously adding “the ISS does not fly over Russia, so all the risks are yours.”

Currently, Russian spacecraft anchored to the ISS are used to alter the station’s trajectory and flightpath, which is necessary to ensure that it can continue to orbit the Earth effectively. Should Russia remove this capability, SpaceX’s “Dragon” capsules could, according to Musk, carry out this function.

SpaceX already has close ties with the ISS, regularly resupplying the station and delivering astronauts, and so this is a potential solution that will likely be assessed carefully.

Whether Musk's assistance will be required is, for the moment, still up in the air.

Originally published on Live Science.

Joe Phelan is a journalist based in London. His work has appeared in VICE, National Geographic, World Soccer and The Blizzard, and has been a guest on Times Radio. He is drawn to the weird, wonderful and under examined, as well as anything related to life in the Arctic Circle. He holds a bachelor's degree in journalism from the University of Chester.