1,500-year-old Roman 'flower pot' was actually a port-o-potty

The preserved eggs of a human intestinal parasite were embedded in the pot's interior.

Don't sniff the fifth-century Roman flower pot. A fifth-century Roman probably pooped in it.

This is the conclusion, more or less, of a new study in which researchers analyzed the crusty build-up found inside a conical ceramic pot dating back 1,500 years.

Once thought to be a flower pot, researchers unearthed the vessel in the bath complex of a Roman villa in Sicily, named the Villa of Gerace. But a microscopic analysis of the pot's internal crust revealed the preserved eggs of whipworm — a parasite that lives in humans’ large intestines.

According to the researchers, that means the pot must have contained human feces at one point. In other words, the flower pot is not a flower pot at all — it’s a chamber pot.

"Conical pots of this type have been recognized quite widely in the Roman Empire and in the absence of other evidence they have often been called storage jars," study co-author Roger Wilson, an archeologist at the University of British Columbia in Canada, said in a statement. "The discovery of many in or near public latrines had led to a suggestion that they might have been used as chamber pots, but until now proof has been lacking."

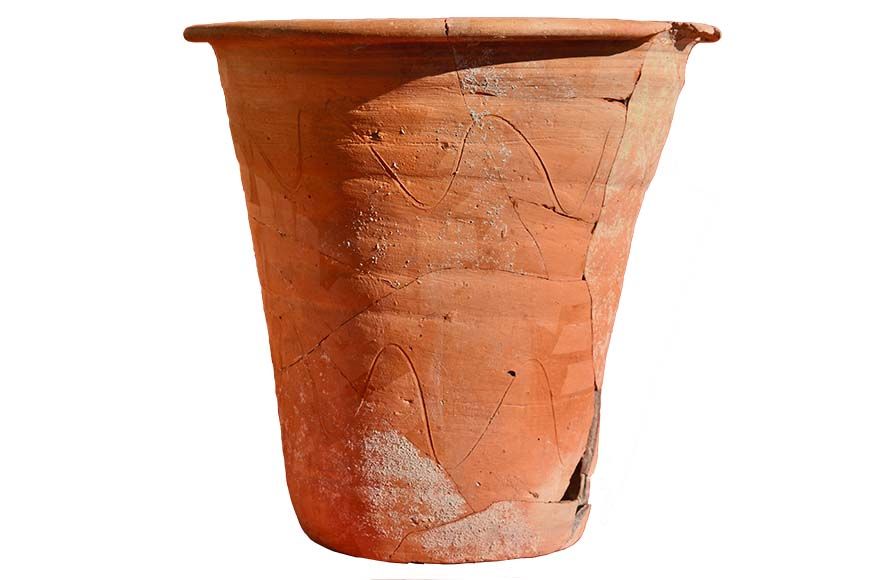

Measuring about 12.5 inches (32 centimeters) high and 13.5 inches (34 cm) wide at the rim, the small ceramic pot looks quite similar to the type you might pick up at a Home Depot to plant a few geraniums in. However, this portable pot would also have proven useful for bathhouse visitors who didn't want to trek to the other side of the villa when nature called. (The villa's bath complex didn’t have built-in latrines, the researchers noted.)

Given the vessel's size, it was likely used in conjunction with a wickerwork or timber chair, with the pot stashed conveniently underneath, the team said.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

After many, many uses, minerals from urine and feces built up in layers inside the chamber pot, forming hard, solid concretions. If any of the pot's users happened to be infected with intestinal parasites, whipworm eggs could have gotten mixed in with those people's feces, and therefore ended up embedded in the pot's concretions, the researchers said.

"We found that the parasite eggs became entrapped within the layers of minerals that formed on the pot surface, preserving them for centuries," study co-author Sophie Rabinow, a graduate student at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., said in the statement.

This study solves the mystery of one little Roman pot, but it could also provide a framework for identifying countless other chamber pots from the era, the researchers said. The key to identifying ancient Roman potties in this manner hinges on the presence of parasite eggs — meaning at least one person infected with intestinal worms would have had to use the pot in question.

Whether or not intestinal infections were a rare occurrence in ancient Rome remains to be discovered. However, the researchers noted, in developing countries today where such infections are endemic, roughly half the population is infected by at least one type of intestinal parasite. If similar trends held in the Roman Empire, then a veritable treasure trove of chamber pots may be out there just waiting to be identified.

This study was published Feb. 11 in the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports.

Originally published on Live Science.

Brandon is the space / physics editor at Live Science. With more than 20 years of editorial experience, his writing has appeared in The Washington Post, Reader's Digest, CBS.com, the Richard Dawkins Foundation website and other outlets. He holds a bachelor's degree in creative writing from the University of Arizona, with minors in journalism and media arts. His interests include black holes, asteroids and comets, and the search for extraterrestrial life.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus