Ripples in space-time could explain the mystery of why the universe exists

A new study may help answer one of the universe's biggest mysteries.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

A new study may help answer one of the universe's biggest mysteries: Why is there more matter than antimatter? That answer, in turn, could explain why everything from atoms to black holes exists.

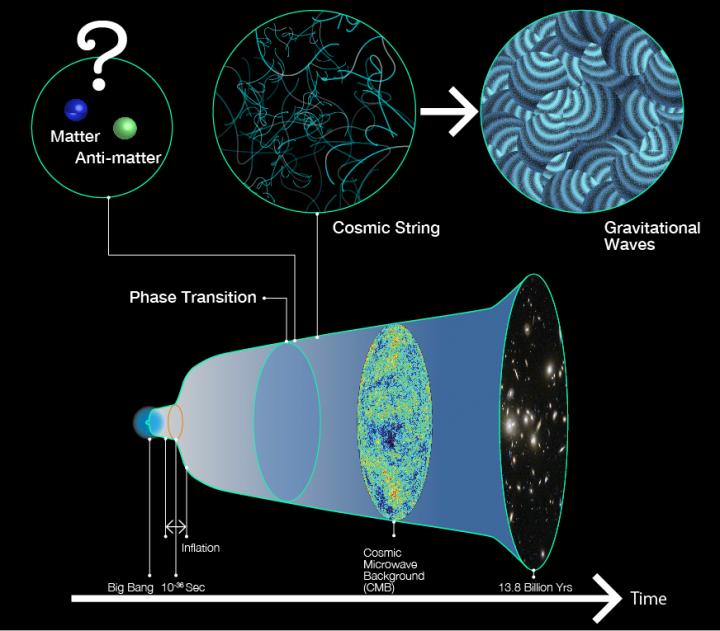

Billions of years ago, soon after the Big Bang, cosmic inflation stretched the tiny seed of our universe and transformed energy into matter. Physicists think inflation initially created the same amount of matter and antimatter, which annihilate each other on contact. But then something happened that tipped the scales in favor of matter, allowing everything we can see and touch to come into existence — and a new study suggests that the explanation is hidden in very slight ripples in space-time.

"If you just start off with an equal component of matter and antimatter, you would just end up with having nothing," because antimatter and matter have equal but opposite charge, said lead study author Jeff Dror, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of California, Berkeley, and physics researcher at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. "Everything would just annihilate."

Related: Twisted physics: 7 mind-blowing findings

Obviously, everything did not annihilate, but researchers are unsure why. The answer might involve very strange elementary particles known as neutrinos, which don't have electrical charge and can act as either matter or antimatter.

One idea is that about a million years after the Big Bang, the universe cooled and underwent a phase transition, an event similar to how boiling water turns liquid into gas. This phase change prompted decaying neutrinos to create more matter than antimatter by some "small, small amount," Dror said. But "there are no very simple ways — or almost any ways — to probe [this theory] and understand if it actually occurred in the early universe."

But Dror and his team, through theoretical models and calculations, figured out a way we might be able to see this phase transition. They proposed that the change would have created extremely long and extremely thin threads of energy called "cosmic strings" that still pervade the universe.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Dror and his team realized that these cosmic strings would most likely create very slight ripples in space-time called gravitational waves. Detect these gravitational waves, and we can discover whether this theory is true.

The strongest gravitational waves in our universe occur when a supernova, or star explosion, happens; when two large stars orbit each other; or when two black holes merge, according to NASA. But the proposed gravitational waves caused by cosmic strings would be much tinier than the ones our instruments have detected before.

However, when the team modeled this hypothetical phase transition under various temperature conditions that could have occurred during this phase transition, they made an encouraging discovery: In all cases, cosmic strings would create gravitational waves that would be detectable by future observatories, such as the European Space Agency's Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) and proposed Big Bang Observer and the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency's Deci-hertz Interferometer Gravitational wave Observatory (DECIGO).

"If these strings are produced at sufficiently high energy scales, they will indeed produce gravitational waves that can be detected by planned observatories," Tanmay Vachaspati, a theoretical physicist at Arizona State University who wasn't part of the study, told Live Science.

The findings were published Jan. 28 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Editor's note: This story was updated to correct the organizations in charge of LISA. It is run by the European Space Agency, not NASA, which is a collaborator on the project.

- 3 ways fundamental particles travel at (nearly) the speed of light

- 18 times quantum particles blew our minds in 2018

- 8 ways you can see Einstein's theory of relativity in real life

OFFER: Save at least 53% with our latest magazine deal!

With impressive cutaway illustrations that show how things function, and mindblowing photography of the world’s most inspiring spectacles, How It Works represents the pinnacle of engaging, factual fun for a mainstream audience keen to keep up with the latest tech and the most impressive phenomena on the planet and beyond. Written and presented in a style that makes even the most complex subjects interesting and easy to understand, How It Works is enjoyed by readers of all ages.

Originally published on Live Science.

Yasemin is a staff writer at Live Science, covering health, neuroscience and biology. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Science and the San Jose Mercury News. She has a bachelor's degree in biomedical engineering from the University of Connecticut and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus