Neptune's Wobbling Moons Are Locked in a Never-Before-Seen Orbital Dance

The twin moons keep each other at arm's length.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered Daily

Daily Newsletter

Sign up for the latest discoveries, groundbreaking research and fascinating breakthroughs that impact you and the wider world direct to your inbox.

Once a week

Life's Little Mysteries

Feed your curiosity with an exclusive mystery every week, solved with science and delivered direct to your inbox before it's seen anywhere else.

Once a week

How It Works

Sign up to our free science & technology newsletter for your weekly fix of fascinating articles, quick quizzes, amazing images, and more

Delivered daily

Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Join the club

Get full access to premium articles, exclusive features and a growing list of member rewards.

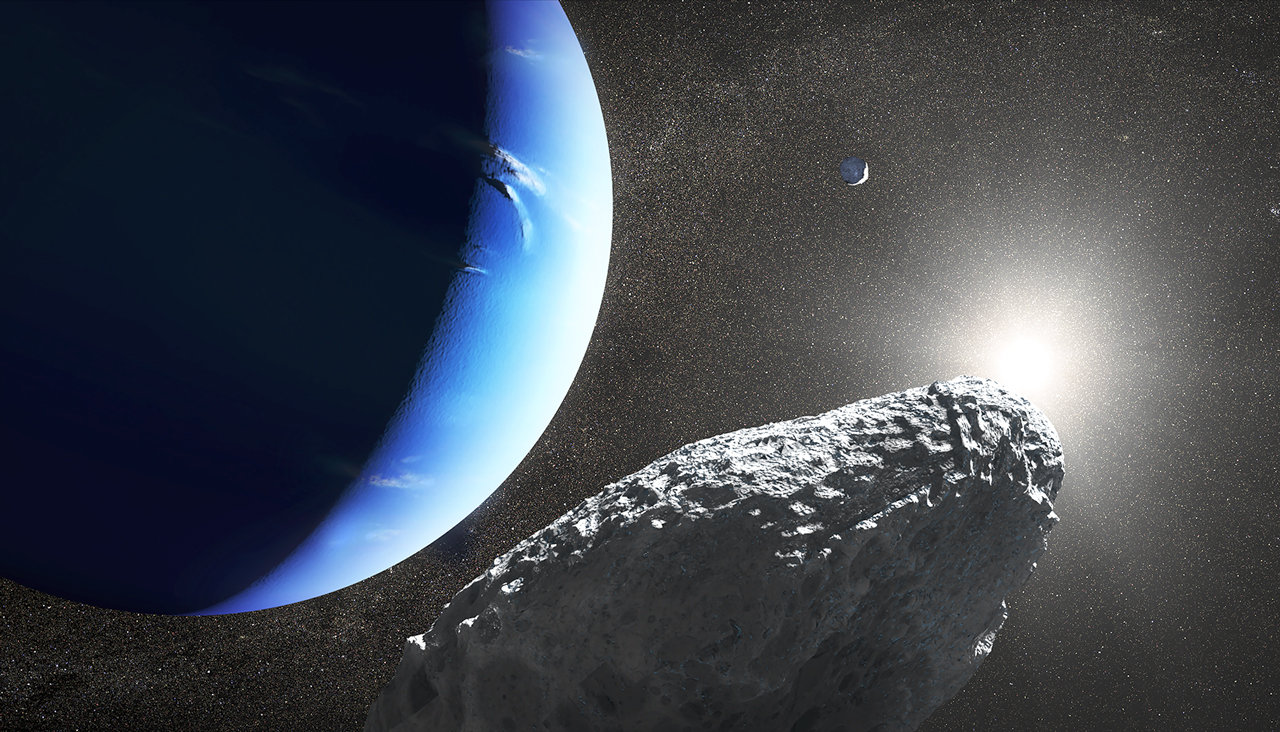

Astronomers have discovered an unusual pattern around Neptune. The gas giant's innermost moons are doing everything in their power to steer clear from one another in a weird, zigzagging pattern that astronomers are calling a "dance of avoidance."

Thalassa and Naiad's orbital paths sit no farther apart than Chicago and Miami, about 1,150 miles (1,850 kilometers). But their zigzagging path around each other as they orbit Neptune ensures that the moons themselves never get that close. Naiad moves faster than Thalassa, circling Neptune in 7 hours versus its twin's orbital time of 7.5 hours. Every time Naiad passes the slower moon, which is when the two would otherwise veer close together, they are in a distant spot in their zigzag dance. At that point, they're about 2,200 miles (3,540 km) apart, or the distance from Chicago to Costa Rica.

Related: What Does It Take to Be a Moon?

This bizarre dance results from a resonance in the twins' orbits that keeps the moons stable as they whirl above Neptune's frigid, blue clouds.

"Resonances work both ways; they can make orbits more or less stable," study co-author Marina Brozović, a NASA Jet Propulsion Laboratory astronomer, and co-author Imke de Pater, a University of California, Berkeley, astronomer, said in a joint email to Live Science. "For the case of Naiad and Thalassa, they are more stable because the resonance maximizes the distance between the moons every time they line up."

The researchers described this bizarre orbit in a paper to be published in a forthcoming issue of the journal Icarus.

Astronomers had never seen a dance quite like this around a planet before, the researchers said, likely because the choreography relies on Naiad's unusual, sharply tilted orbit. This weird pattern had remained hidden so long because it's quite difficult to study relatively little objects around the most distant planet in our solar system.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

"They are small and orbit very close to the planet, so they get lost in a bright glare of Neptune," Brozović and de Pater said. "The Hubble Space Telescope just returned a treasure trove of data that were published in February, 2019, in [the journal] Nature, so we were able to calculate the best orbits yet."

For a viewer standing on either moon, the other satellite would appear to wiggle crazily across the sky as it passed. From Thalassa's northern end, you'd seed Naiad zip overhead once before traveling over the north again on its next pass. Then, you could zoom around to the other side of the moon (if you had a superfast vehicle) and see the twin moon pass once and then twice over the south.

It's not clear how long the two little moons, much smaller than Earth's and influenced by the gravity of a much larger planet, have been locked in this pattern, the researchers said. Too much is unknown, most importantly the precise mechanics of how energy from the moons' orbits gets transfered down to Neptune. (On Earth, we see the effects of such a transfer in our tides.) But for the moment, the unusual resonance seems to protect the moons from one another, keeping them at a comfortable, stable arm's length.

- The 9 Biggest Unsolved Mysteries in Physics

- The Large Numbers That Define the Universe

- Twisted Physics: 7 Mind-Blowing Findings

Originally published on Live Science.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus