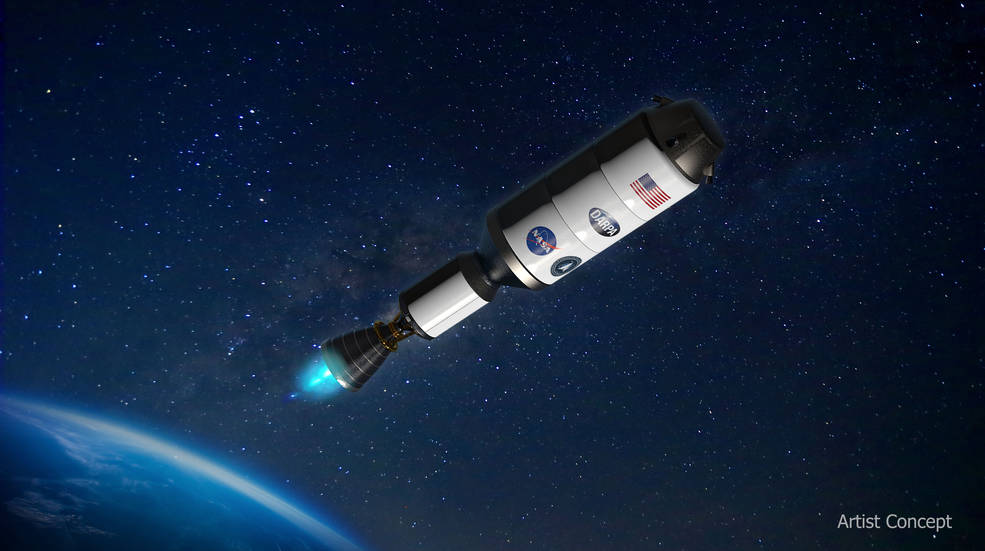

NASA to test nuclear rocket engine that could take humans to Mars in 45 days

This is the first time a nuclear powered engine has been tested in fifty years

NASA has revealed plans to create a nuclear-powered rocket that could send astronauts to Mars in just 45 days.

The agency, which has partnered with the Pentagon’s Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to design the rocket, announced on Tuesday (Jan. 24) that it could build a working nuclear thermal rocket engine as soon as 2027.

NASA’s current rocket systems (including the Space Launch System which last year sent the Artemis 1 rocket on a historic round-trip to the moon) are based on the century-old, traditional method of chemical propulsion — in which an oxidizer (which gives the reaction more oxygen to combust with) is mixed with flammable rocket fuel to create a flaming jet of thrust. The proposed nuclear system, on the other hand, will harness the chain reaction from tearing apart atoms to power a nuclear fission reactor that would be “three or more times more efficient” and could reduce Mars flight times to a fraction of the current seven months, according to the agency.

Related: To the moon! NASA launches Artemis 1, the most powerful rocket ever built

"DARPA and NASA have a long history of fruitful collaboration in advancing technologies for our respective goals, from the Saturn V rocket that took humans to the Moon for the first time to robotic servicing and refueling of satellites," Stefanie Tompkins, the director of DARPA, said in a statement. "The space domain is critical to modern commerce, scientific discovery, and national security. The ability to accomplish leap-ahead advances in space technology… will be essential for more efficiently and quickly transporting material to the moon and, eventually, people to Mars."

NASA began its research into nuclear thermal engines in 1959, eventually leading to the design and construction of the Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application (NERVA), a solid-core nuclear reactor that was successfully tested on Earth. Plans to fire the engine in space, however, were mothballed following the 1973 end of the Apollo Era and a sharp reduction of the program's funding.

Nuclear engines can fire more efficiently than their chemical counterparts, and for extended periods of time — propelling rockets faster and further. They are split into two types: Nuclear Electric Propulsion (NEP) reactors, which work by generating electricity that strips electrons from noble gases such as xenon and krypton before blasting them out of the spacecraft’s thruster as an ion beam; and Nuclear Thermal Propulsion (NTP) reactors, which is the type being investigated by NASA, uses the fission reaction to heat a gas (typically hydrogen or ammonia) so that it expands through a nozzle to provide thrust.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

The Artemis 1 flight was the first of three missions testing the hardware, software and ground systems intended to one day establish a base on the moon and transport the first humans to Mars. This first test flight will be followed by Artemis 2 and Artemis 3 in 2024 and 2025/2026, respectively. Artemis 2 will make the same journey as Artemis 1 but with a four-person human crew, and Artemis 3 will send the first woman and the first person of color to land on the moon's surface, at the lunar south pole.

"It's historic because we are now going back into space, into deep space, with a new generation." NASA Administrator Bill Nelson said following Artemis 1’s launch. "One that marks new technology, a whole new breed of astronauts, and a vision of the future. This is the program of going back to the moon to learn, to live, to invent, to create in order to explore beyond."

Ben Turner is a U.K. based writer and editor at Live Science. He covers physics and astronomy, tech and climate change. He graduated from University College London with a degree in particle physics before training as a journalist. When he's not writing, Ben enjoys reading literature, playing the guitar and embarrassing himself with chess.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus