NASA's Mars Helicopter Ingenuity is 'go' for historic 1st flight on Sunday

Humanity's first helicopter on Mars has been cleared for a historic takeoff.

Ingenuity will take to the skies above Jezero Crater Sunday (April 11) on a 40-second flight — roughly four times longer than the Wright brothers' first flight on Earth over 117 years ago. The first data, successful or not, should flow back to Earth on Monday (April 12) around 3:30 a.m. EDT (0830 GMT).

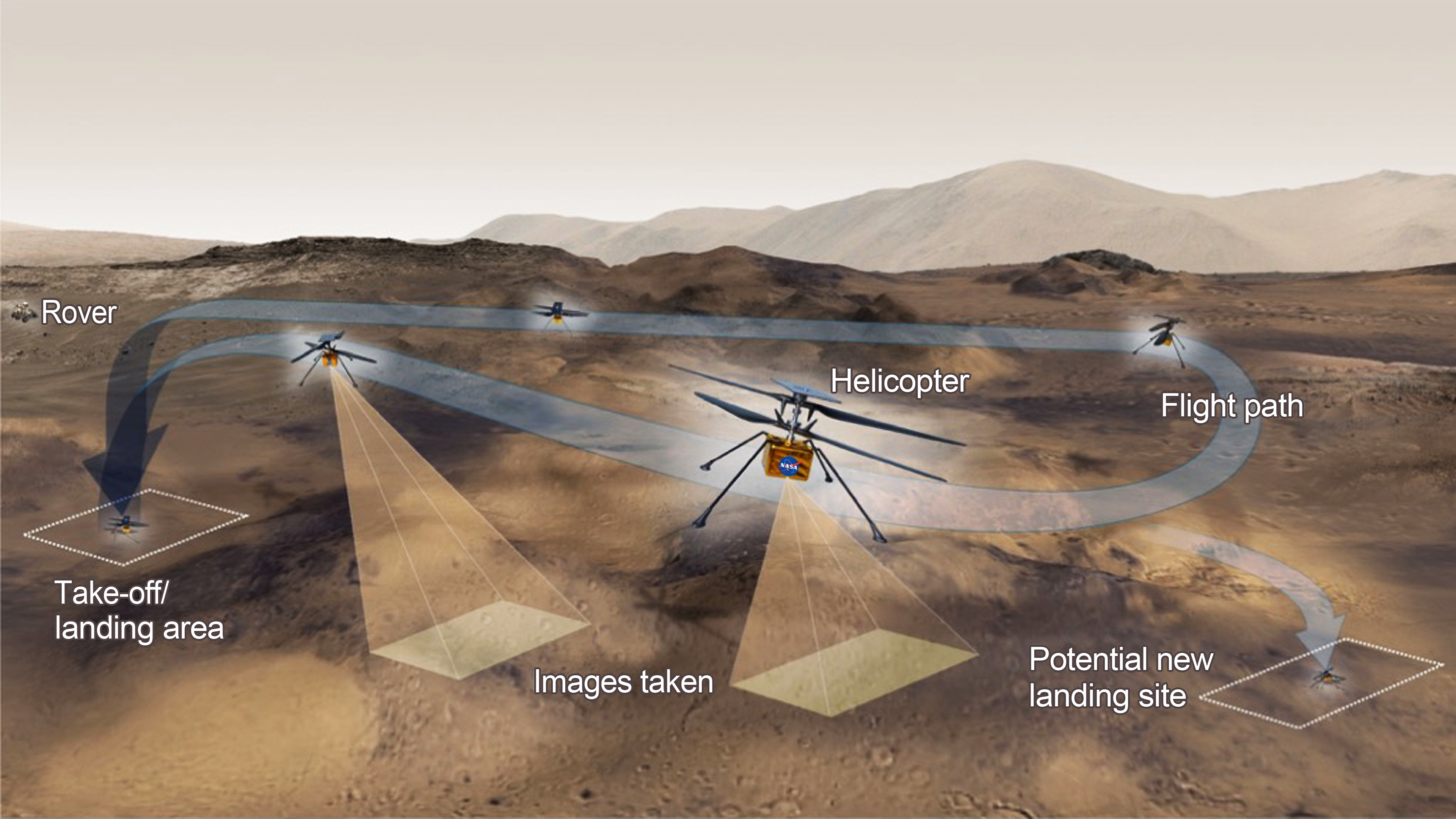

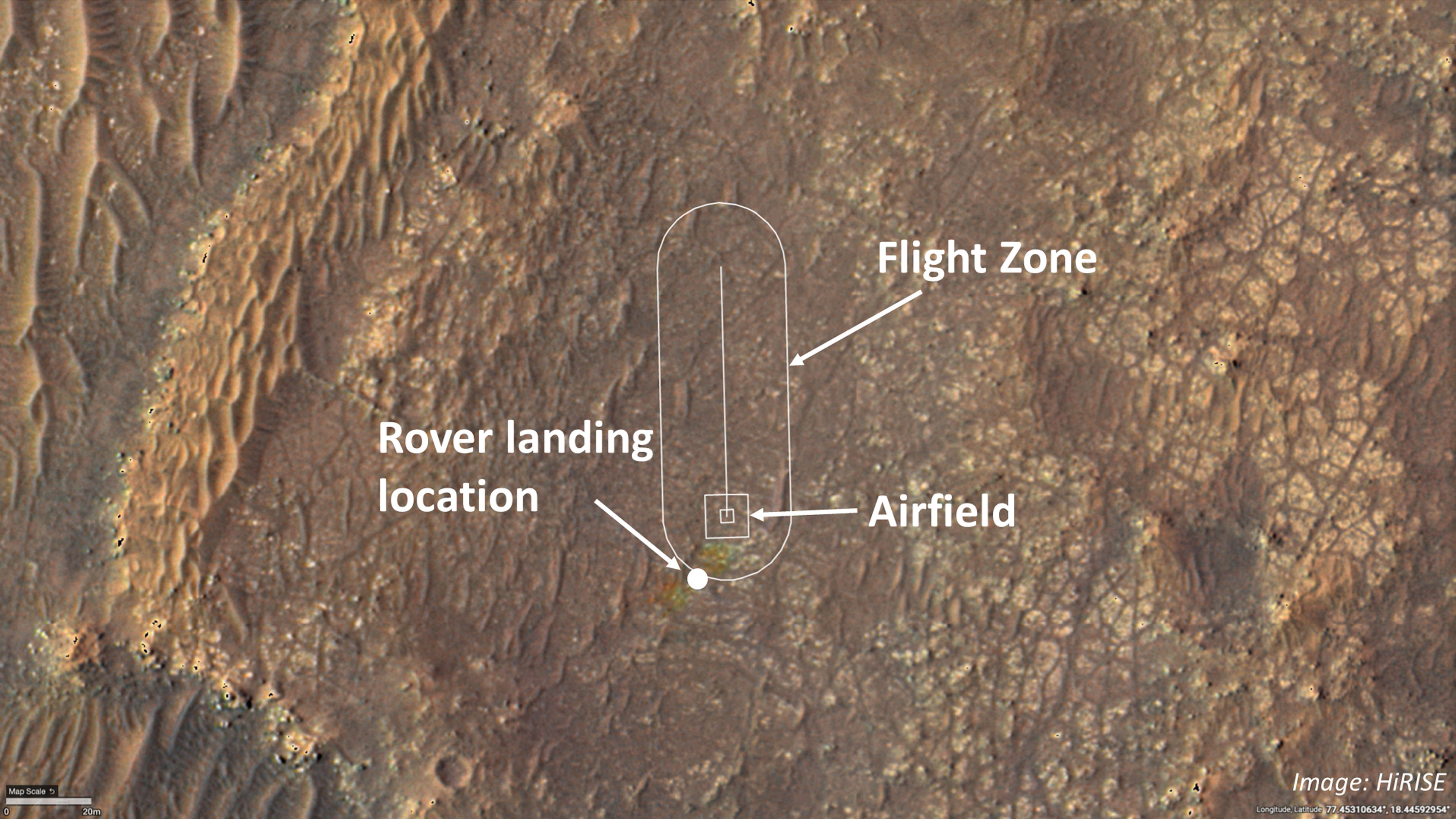

The flight plan has the Martian whirlybird hovering just 9 feet (3 meters) above the surface, collecting black-and-white data of landmarks beneath it along with a high-definition horizon video and engineering data. The flight will also take place under the watchful camera of the Perseverance rover, parked about 200 feet (60 meters) away from Ingenuity's launch site.

Related: How to watch the Mars helicopter Ingenuity's first flight online

"Naturally the team is working really hard to be ready for that moment [of flight], so when we see that first data, that it works … it will be an incredible moment," said Tim Canham, Ingenuity operations lead, during a livestreamed press conference from NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, on Friday (April 9).

We've been imagining flight on Mars in fiction since at least 1890, when Robert Cromie's "A Plunge Into Space" depicted Martian airships taking to the thin atmosphere. While the drone-sized Ingenuity will be a simple up-and-down sojourn, the vision for its flight is no less ambitious.

The Martian atmosphere is just 1% as dense as that of Earth, so the helicopter must provide more lift than it would need to fly on Earth. The helicopter must also fly autonomously, since controllers on Earth are parked too far away to joystick it around the crater. It needs to keep recharging from the sun and survive nightly surface temperatures of minus 130 degrees Fahrenheit (minus 90 degrees Celsius). It took years of testing, flights of varying success in air chambers and a long journey to Mars to get this far.

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

MiMi Aung, Ingenuity project manager at JPL, said she will be most excited by the black-and-white camera images that the helicopter will ferry back to Earth, showing its view from the air. "The images will be inspiring," she said in the briefing, admitting it will be hard to imagine how she will feel since the team has not tried to assume success from the ambitious flight test.

If Ingenuity makes it and transmits data as planned, the black-and-white downward-facing camera images will be taken about 30 times a second and have the capability to track features on the surface; in the long run, once all these images get down to Earth, controllers will be able to estimate rate and direction of motion by looking at feature drift.

There will also be a 13-megapixel camera on Ingenuity pointing towards the horizon, which will take a few pictures during the flight. Extensive engineering data will also be gathered with the pictures, such as the altimeter's readouts — data that will be used to benefit future flying vehicles. NASA's long-term vision is to employ drones that could one day climb to areas out-of-reach from current rovers, such as potential regions of habitability on the desert-like Red Planet. The drones could scout ahead for robots and humans alike and help to map out routes even more efficiently than we do today from orbit.

The solar powered Ingenuity will inform the design of these future robots. The helicopter team has 30 Martian sols (roughly 31 days on Earth) to take the first tentative flights. Assuming Ingenuity survives the first flight, it will rest and transmit data before attempting a second flight with lateral movement. Subsequent flights will happen every three or four Martian sols. The fifth flight — if Ingenuity gets that far — will be a chance to really soar. "The probability is it would be unlikely it will land safely because we will go into unsurveyed areas," Aung said.

Ingenuity is the product of about five years of flight tests in altitude chambers simulating Martian conditions at JPL, including a test of the little helicopter itself in 2019 that went exactly to plan. The engineers thus know it is theoretically possible to fly on Mars, and have a weather station available on Perseverance to approve or wave off the flight given current conditions, but there is still the element of uncertainty in the moment.

Additional challenges come in sending everything back from Ingenuity and Perseverance. For example, the planned five-minute flight video from the rover, in 4K definition, would take months to send back to Earth given the bandwidth availability from the Martian surface through the NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter to NASA's Deep Space Network of dishes that pick up information from distant spacecraft.

JPL thus plans instead to preselect some key frames from that video and send those back, hoping that at least one of the frames depict Ingenuity taking to the air. The Mastcam-Z panoramic camera team is also simulating taking footage from afar, aiming to get Ingenuity exactly in frame from a distance, as it aims to capture zoomed-in and zoomed-out footage at the same time.

Its best video resolution is seven frames a second, but only a portion of that frame will be captured and then compressed to send back to Earth. Already practice is taking place; Mastcam-Z sent back a short video of the helicopter revving up its blade to 50 revolutions per second, but that was on the ground.

Getting the angle right to catch Ingenuity in the air will be "really hard," said Elsa Jensen, Mastcam-Z uplink operations lead at Malin Space Science Systems, at the same briefing. Mastcam-Z is designed for large swaths of terrain, while Ingenuity's flight will only take place in a tiny portion of the overall camera frame's view. "We hope everything will go well on Sunday, but we know there will be surprises. That's what we trained for," she said.

The rover team may also try to capture the sound of future flights of Ingenuity with Perseverance's SuperCam microphone, but there are no plans to do that for the first excursion. "It's very touch-and-go if we can hear anything from that distance," Canham said, adding discussions are ongoing as to when to record. "Worst comes to worse, maybe we'll get a lot of nothing," he joked of the audio footage.

The last time NASA took such an ambitious step on the Red Planet was with the Sojourner rover, a breadboxed-size vehicle that rolled on the surface for a few short months in 1997 and nestled up to rocks like a little puppy.

This first mobile Martian vehicle was similarly a test to see if rovers could take on the rugged terrain on Mars far from immediate help from Earth. It worked beyond expectations, pioneering a generation of NASA rover explorers (Spirit, Opportunity, Curiosity and now Perseverance) who have scouted for water and signs of ancient habitability; Perseverance, if all goes to plan, will participate in a larger sample-return mission that will bring rocks it caches back to Earth for detailed analysis.

Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA associate administrator for science, said at the press conference that Ingenuity would hold a similar role in NASA history as Sojourner did. "We're ready for another historic moment," he said.

Follow Elizabeth Howell on Twitter @howellspace. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Elizabeth Howell was staff reporter at Space.com between 2022 and 2024 and a regular contributor to Live Science and Space.com between 2012 and 2022. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, speaking several times with the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

Live Science Plus

Live Science Plus