Lasers reveal massive, 650-square-mile Maya site hidden beneath Guatemalan rainforest

While conducting an aerial survey of northern Guatemala, researchers detected a sprawling Maya site.

Geologists in northern Guatemala have discovered a massive Maya site that stretches approximately 650 square miles (1,700 square kilometers) and dates to the Middle and Late Preclassic period (roughly 1000 B.C. to 250 B.C.).

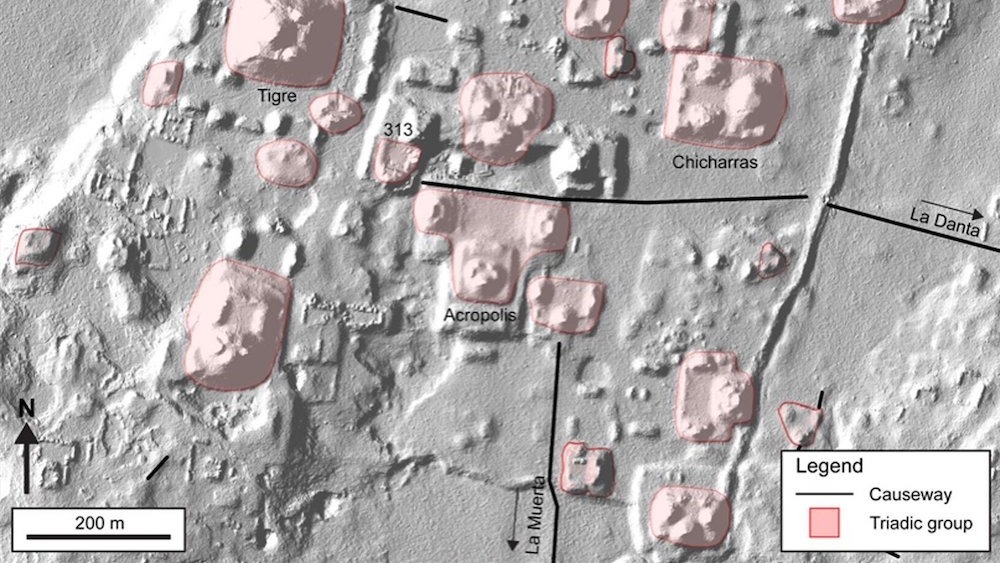

The findings were the result of an aerial survey that researchers conducted via airplane using lidar (light detection and ranging), in which lasers are beamed out and the reflected light is used to create aerial imagery of a landscape. The technology is particularly beneficial in areas such as the rainforests of Guatemala's Mirador-Calakmul Karst Basin, where lasers can penetrate the thick tree canopy.

Using data from the scans, the team identified more than 1,000 settlements dotting the region, which were interconnected by 100 miles (160 kilometers) of causeways that the Maya likely traversed on foot. They also detected the remains of several large platforms and pyramids, along with canals and reservoirs used for water collection, according to the study, which was published Dec. 5 in the journal Ancient Mesoamerica.

The lidar data showed "for the first time an area that was integrated politically and economically, and never seen before in other places in the Western Hemisphere," study co-author Carlos Morales-Aguilar, a postdoctoral fellow in the Department of Geography and the Environment at the University of Texas at Austin, told Live Science in an email. "We can now see the entire landscape of the Maya region" in this section of Guatemala, he said.

Related: What's hidden inside the ancient Maya pyramids?

So, what made this region so enticing that the Maya would want to settle there in the first place?

"For the Maya, the Mirador-Calakmul Karst Basin was the 'Goldilocks Zone,'" study co-author Ross Ensley, a geologist with the Institute for Geological Study of the Maya Lowlands in Houston, told Live Science in an email. "The Maya settled in [this region] because it had the right mix of uplands for settlement and lowlands for agriculture. The uplands provided a source for limestone, their primary building material, and dry land to live on. The lowlands are mostly seasonal swamps, or bajos, which provided space for wetland agriculture as well as organic-rich soil for use in terraced agriculture."

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Researchers have previously used lidar to scan Maya sites in Guatemala. In 2015, an initiative called the Mirador Basin Project conducted two large-scale surveys of the southern portion of the basin, focusing on the ancient city of El Mirador. That project led to the mapping of 658 square miles (1,703 square km) of this section of the country, according to the study.

"When I generated the first bare-earth models of the ancient city of El Mirador, I was blown away," Morales-Aguilar said. "It was fascinating to observe for the first time the large number of reservoirs, monumental pyramids, terraces, residential areas and small mounds."

Researchers hope lidar technology will help them explore sections of Guatemala that have remained a mystery for centuries.

"Lidar has been revolutionary for archaeology in this area, especially if it's covered in tropical forest where visibility is limited," Marcello Canuto, director of the Middle American Research Institute at Tulane University and an anthropologist who wasn't involved in the study, told Live Science. "While surveying, we tend see a small part of the causeway, but lidar lets us see things that are big and linear. This research lets us see the area for the first time; the fact that we have this data is transformative."

Jennifer Nalewicki is former Live Science staff writer and Salt Lake City-based journalist whose work has been featured in The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, Popular Mechanics and more. She covers several science topics from planet Earth to paleontology and archaeology to health and culture. Prior to freelancing, Jennifer held an Editor role at Time Inc. Jennifer has a bachelor's degree in Journalism from The University of Texas at Austin.